The Memory of Water

An extract from the Tabloid textbook serves as the starting point for this curriculum and initiates the connection between the chest and the themed subject matter presented. Entries are drawn from the larger depository of materials for this curriculum and each entry builds on the previous one in an associative manner and should be carefully considered, before moving on to the next item.

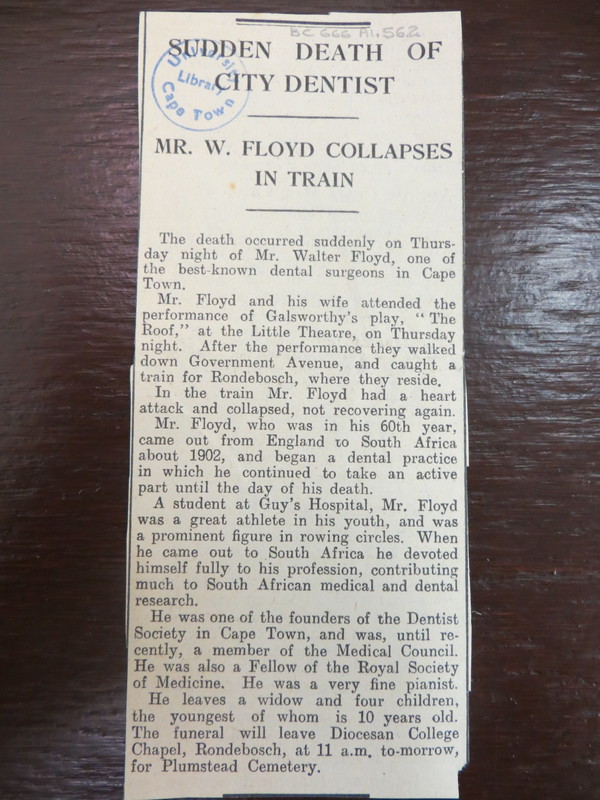

"The BWC shop was located a short walk from Walter Floyd’s dental practice which he bought in 1904 (for £2,404 16s 8d) and shared with his partner, William Johnston. It is uncertain when Floyd first came out to South Africa, but records prove that he was living here by January 1902 (Hart & Lydall, 1981: 1)" (Liebenberg 2021: 52).

In interviews with Mary Floyd in 2015, I showed her this photo of her father-in-law on the boat, en route to Cape Town, and asked her whether she knew who the woman in the photo was. (She appeared in quite a few photos of Floyd's from this period – one especially intimate one showing her lying on a beach and smiling coyly at the photographer.) Was it Agnes (his wife), perhaps? She said it definitely wasn't.

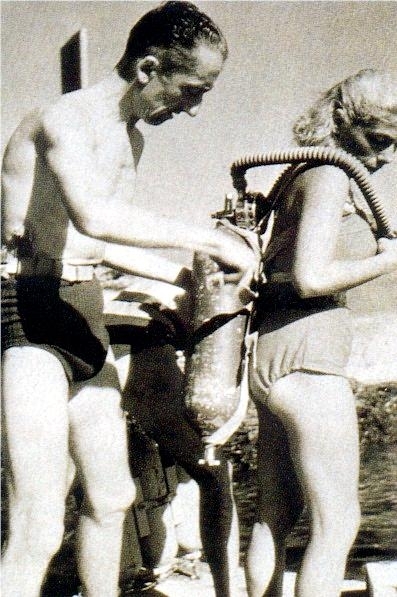

In 1963 Simone Melchior became the world's first female aquanaut by living in Starfish House, an underwater habitat, for the final four days of the Conshelf II project.

Although never visible in the 'Undersea World of Jacques Cousteau' series, Cousteau's wife and business partner played a key role in the operation at sea. She was the acting mother, healer, nurse and psychiatrist to the all-male crew for 40 years. Cousteau describes her as being "happiest out of camera range, in the crow’s nest of the Calypso (...), scanning the sea for whales".

Her father, Henri Melchior, was director of Air Liquide (France’s main producer of industrial gases at the time) and funded the invention of the aqua lung and the scuba diving apparatus we know today.

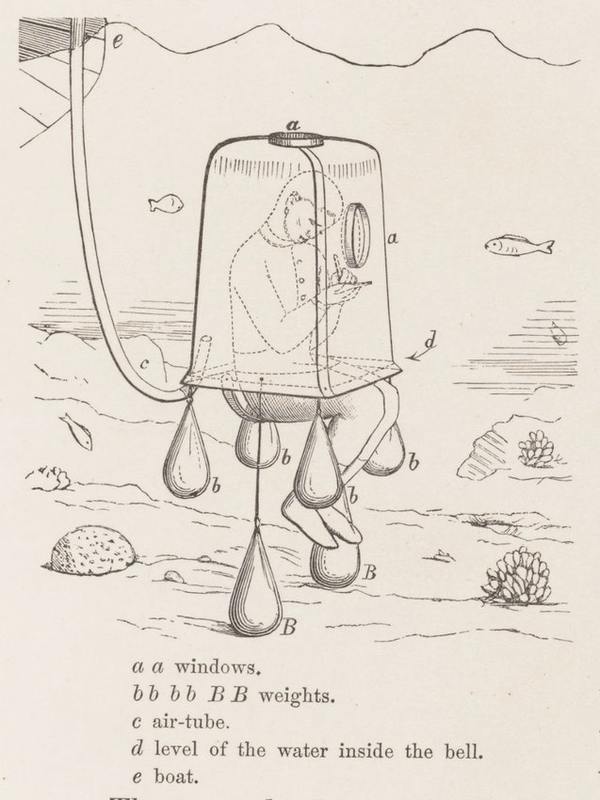

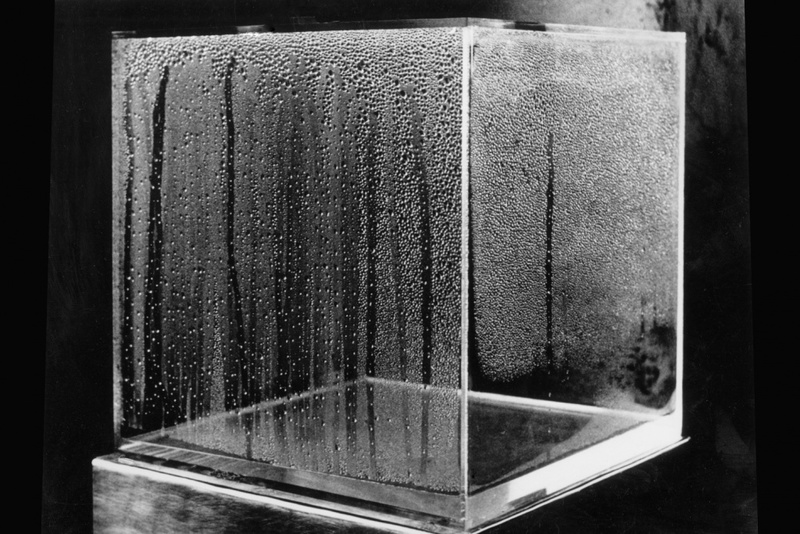

"Measuring three feet high by two and half wide and deep, this submersible, of sheet iron and inch-thick glass, had the user's legs sticking out of the bottom so that he could propel himself along the seabed at a depth of five meters or so. It was weighed down by cannonballs, and with air pumped in, the diving bell allowed him to descend for sessions of up to three hours" (The Public Domain Review 2021).

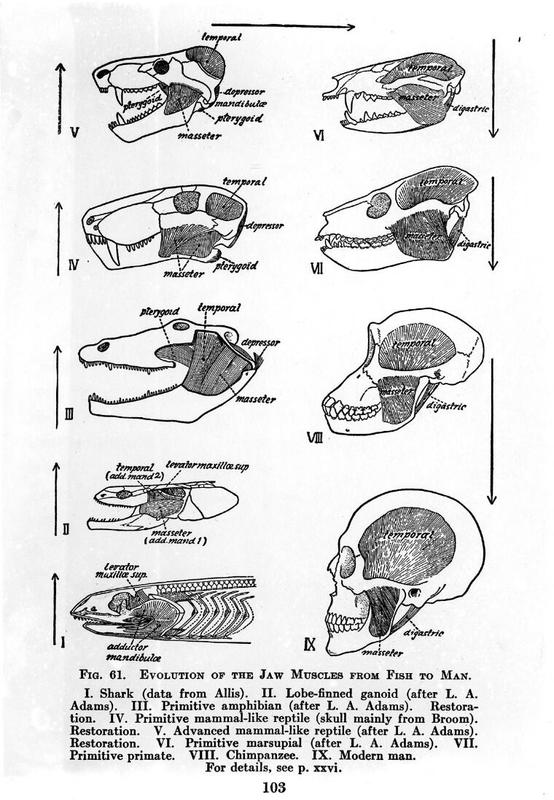

"Our hands resemble fossil fins; our heads are organised like those of long extinct jawless fish and major parts of our genomes still look and function like those worms and bacteria" (Shubin 2008).

During the summer of his second year of study, paleontologist and evolutionary biologist, Neil Shubin, discovered a particular fossil fish in the Arctic, naming it the Tiktaalik. In Your Inner Fish: A Journey into the 3.5-Billion-Year History of the Human Body (2009) he explored the connections in our human anatomy with those fishes that ventured onto land over 375 million years ago, based on the information gathered from studying the Tiktaalik.

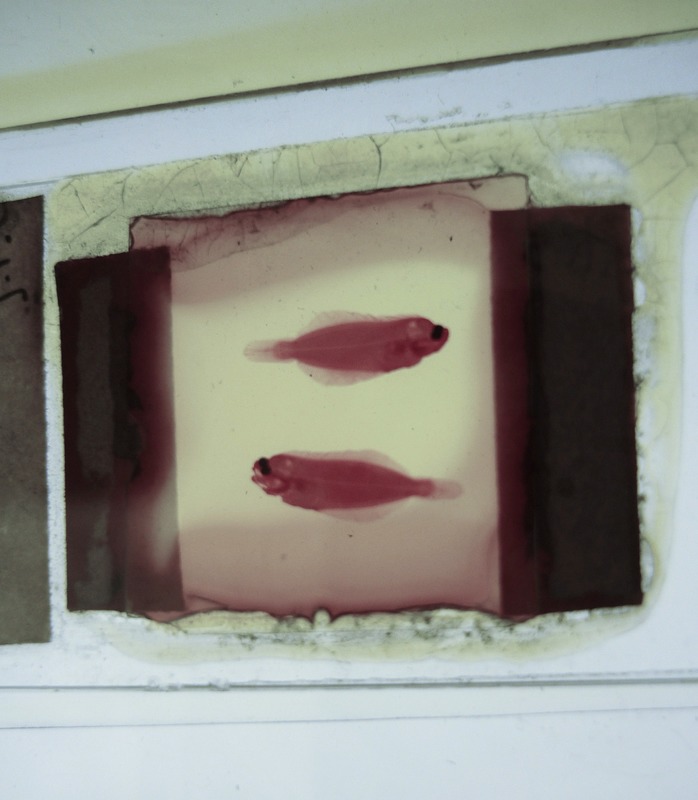

Addressing the fact that 95% of known animal species are smaller than our thumbs, yet natural history museums displays are filled with mostly large animals, this sub-museum shows the legs of a flea highlighting its muscles; a whole squid, just a couple of millimetres long; beetles that have been sliced along their entire length, through the antennae, head, legs and body — 1/10th of a millimetre thick; as well as these two baby flounder fish.

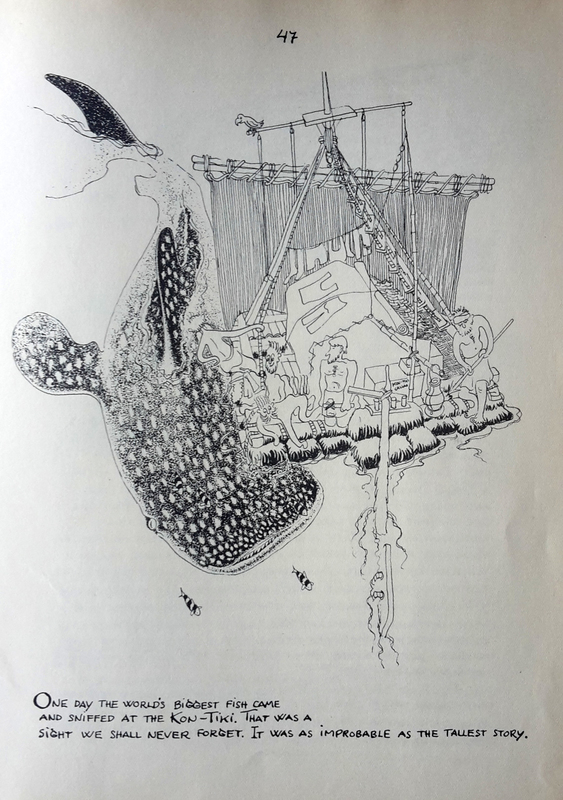

Whale sharks (Rhincodon typus) are the largest shark, and indeed largest of any fishes alive today. These gentle marine giants roam the oceans around the globe, generally alone. They only feed on plankton. In the Norwegian explorer, Thor Theyerdal's account of his journey by raft across the Pacific Ocean from South America to the Polynesian islands in 1947, the crew is visited by one of these curious and benign creatures:

"In reality the whale shark went on encircling us for barely an hour, but to us the visit seemed to last a whole day. At last it became too exciting for Erik, who was standing at a corner of the raft with an eight-foot hand harpoon, and, encouraged by ill-considered shouts, he raised the harpoon above his head. As the whale shark came gliding slowly toward him and its broad head moved right under the corner of the raft, Erik thrust the harpoon with all his giant strength down between his legs and deep into the whale shark’s gristly head. It was a second or two before the giant understood properly what was happening. Then in a flash the placid half-wit was transformed into a mountain of steel muscles. We heard a swishing noise as the harpoon line rushed over the edge of the raft and saw a cascade of water as the giant stood on its head and plunged down into the depths. The three men who were standing nearest were flung about the place, head over heels, and two of them were flayed and burned by the line as it rushed through the air. The thick line, strong enough to hold a boat, was caught up on the side of the raft but snapped at once like a piece of twine, and a few seconds later a broken-off harpoon shaft came up to the surface two hundred yards away" .

Extract from Theyerdal, T. 2010. Kon-tiki. New York: Skyhorse Publishing.

"When it (the chest) is not being exhibited in the Iziko South African Museum, it lives in the archives of the University of Cape Town. As part of an institution that has sworn dedication to decolonising its curriculum, it poses a somewhat latent threat. In a speech in 2015, the writer and previous vice-chancellor of the University of Cape Town, Professor Njabulo Ndebele, stated "that there can be no transformation of the curriculum, or indeed of knowledge itself, without an interrogation of archive". It is an argument which strongly suggests that a critical assessment of the archival legacy on which the institution is founded becomes of pivotal importance when developing a decolonial institution.

What worth then, if any, does this dormant object serve in a new curriculum?"

Extract from a paper delivered at the BSHS conference in Cambridge, 2019

“Her purse is half open, and I see a hotel room key, a metro ticket, and a hundred-franc note folded in four, like objects brought back by a space probe sent to earth to study how earthlings live, travel, and trade with one another. The sight leaves me pensive and confused. Does the cosmos contain keys for opening up my diving bell? A subway line with no terminus? A currency strong enough to buy my freedom back? We must keep looking. I'll be off now".

An extract from Jean-Dominique Bauby's The Diving Bell and the Butterfly, the memoir which he dictated after suffering a stroke in 1995. The stroke rendered him mute and almost completely paralyzed, except for the movement of his left eyelid. Bauby dictated his memoir through blinking as his speech therapist listed the letters of the alphabet. When his doctor told him his prognosis, he mentioned that in the past , he would have simply died from this type of stroke, but that improved resuscitation techniques had now prolonged and refined the agony of this condition: "You survive, but you survive with what is so aptly known as 'locked-in syndrome'”.

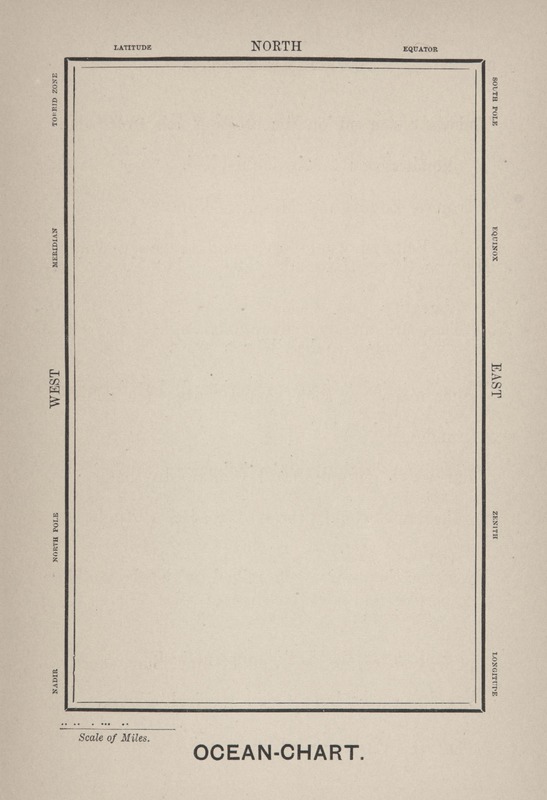

"The Hunting of the Snark offers a timely caution for geographical investigation. The danger, both academic and pragmatic, of enslavement to static conceptual categories, rigid classifications, and established methodological procedures is simply that they tend to rule out the possibility of experiencing that insight and understanding which can be neither discovered, formulated nor communicated by adherence to traditional investigative methdologies. This is not to advocate an un-methodical and irrational geographical philosophy, but rather to suggest that there may be conditions under which slavish adherence to a tried and tested methodology may fail to provide reliable guidance in our search for understanding. A lack of commitment to open-ended investigation could mean that, because our methods are inappropriate, our explorations will forever remain, so to speak, 'snarked' ".

Extract from: Livingstone, D. N & Harrison, R.T. 1981. Hunting the Snark: Perspectives on Geographical Investigation. Geografiska annaler. Series B, Human geography. 63 (1): 69–72.

Katie Paterson

2007–08

Vatnajökull (the sound of)

A live phone line was created to an Icelandic glacier, via an underwater microphone submerged in Jökulsárlón lagoon, an outlet of Vatnajökull. The number 07757001122 could be called from any telephone in the world, and the listener would hear the sound of the glacier melting.

An extract from J.D. Salinger's For Esmé - With Love and Squalor in which Seymour Glass interacts with a young girl while swimming in the ocean on holiday. The story is called 'A perfect day for Bananafish'.

“Miss Carpenter. Please. I know my business,” the young man said. “You just keep your eyes open for any bananafish. This is a perfect day for bananafish.”

“I don’t see any,” Sybil said.

“That’s understandable. Their habits are very peculiar.” He kept pushing the float. The water was not quite up to his chest. “They lead a very tragic life,” he said. “You know what they do, Sybil?”

She shook her head.

“Well, they swim into a hole where there’s a lot of bananas. They’re very ordinary-looking fish when they swim in. But once they get in, they behave like pigs. Why, I’ve known some bananafish to swim into a banana hole and eat as many as seventy-eight bananas.” He edged the float and its passenger a foot closer to the horizon. “Naturally, after that they’re so fat they can’t get out of the hole again. Can’t fit through the door.”

“Not too far out,” Sybil said. “What happens to them?”

“What happens to who?”

“The bananafish.”

“Oh, you mean after they eat so many bananas they can’t get out of the banana hole?”

“Yes,” said Sybil.

“Well, I hate to tell you, Sybil. They die.”

“Why?” asked Sybil.

“Well, they get banana fever. It’s a terrible disease.”

“Here comes a wave,” Sybil said nervously.

“We’ll ignore it. We’ll snub it,” said the young man. “Two snobs.” He took Sybil’s ankles in his hands and pressed down and forward. The float nosed over the top of the wave. The water soaked Sybil’s blond hair, but her scream was full of pleasure.

With her hand, when the float was level again, she wiped away a flat, wet band of hair from her eyes, and reported, “I just saw one.”

“Saw what, my love?”

“A bananafish.”

“My God, no!” said the young man. “Did he have any bananas in his mouth?”

“Yes,” said Sybil. “Six.”

The young man suddenly picked up one of Sybil’s wet feet, which were drooping over the end of the float, and kissed the arch.

“Hey!” said the owner of the foot, turning around.

“Hey, yourself! We’re going in now. You had enough?”

“No!”

“Sorry,” he said, and pushed the float toward shore until Sybil got off it.

He carried it the rest of the way.

(Salinger 1986: 20-21).

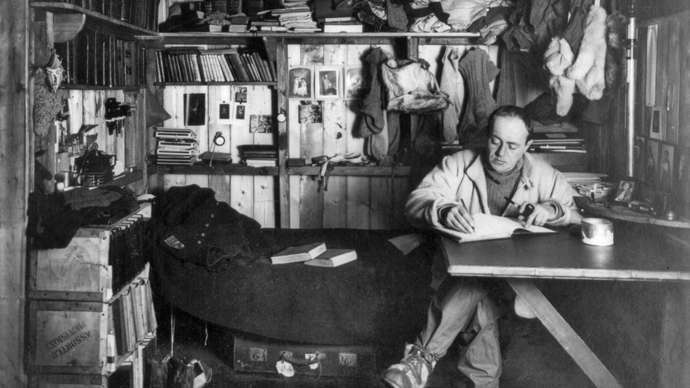

Robert Falcon Scott’s Terra Nova expedition reached the South Pole on 17 January 1912 — 23 days too late. Inside a small tent supported by a single bamboo flying a Norwegian flag, was a record of the five who had been the first to reach the pole: Roald Amundsen, the leader, and his team - Olav Olavson Bjaaland, Hilmer Hanssen, Sverre H. Hassel and Oscar Wisting.

On 19 January, they began their 1,300 kilometre journey home, Scott writing: “I’m afraid the return journey is going to be dreadfully tiring and monotonous” (Scott 1914: 548).

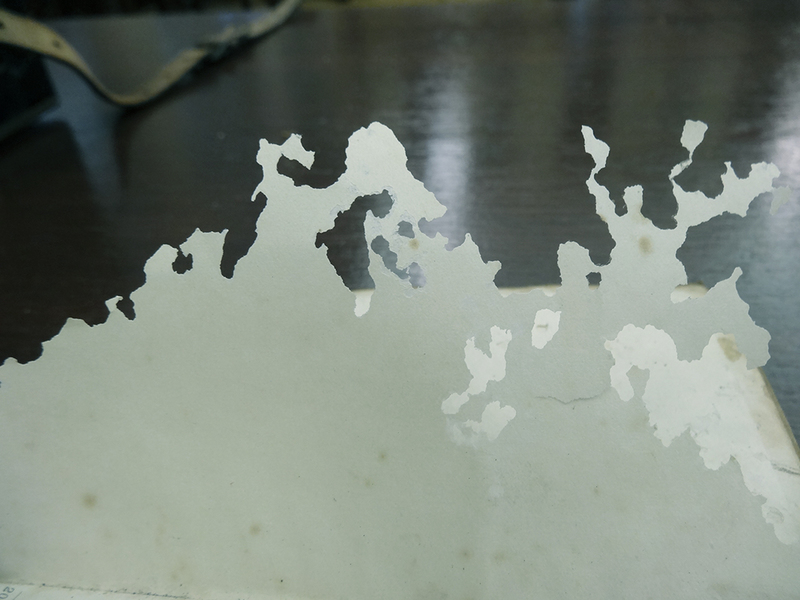

On 18 April 2021, the Jagger Library — the medicine chest's home — caught fire. The fire started on the lower sections of Rhodes Memorial at the foot of Table Mountain, and set alight landscape, monuments, and many of the university’s buildings. The library only caught fire in the late afternoon, but became a raging inferno as books, artworks, manuscripts that were worked on frequently, institutional, and administrative records of Special Collections, as well as the entire African Film collection, all went up in flames.

After initially making good progress, Terra Nova expedition party’s prospects steadily worsened as they struggled northward. Deteriorating weather, frostbite, snow blindness, hunger and exhaustion lead to Edgar Evans dying on 17 February and Lawrence Oates, whose condition was aggravated by an old war-wound to the extent that he was barely able to walk, voluntarily leaving his tent on 16 March and walking to his death. (“I am just going outside and may be some time".)" (Liebenberg 2011: 75).

"In Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men, Crooks consoles the simple, unaffected and kindly Lennie when his friend, George, doesn’t return from town. He tells him he should be glad that he at least has someone.

'S’pose you didn’t have nobody. S’pose you couldn’t get into the bunk-house and play rummy ‘cause you was black. How’d you like that? (…) A guy sits alone out here at night, maybe readin’ books or thinkin’ or stuff like that. Sometimes he gets thinkin’ an’ he got nothing to tell him what’s so an’ what ain’t so. Maybe if he sees somethin’, he don’t know whether it’s right or not. He can’t turn to some other guy and ast him if he sees it too. He can’t tell. He got nothing to measure by. I seen things out here. I wasn’t drunk. I don’t know if I was asleep. If some guy was with me, he could tell me I was asleep, an’ then it would be alright. But I jus’ don’t know' "(Steinbeck 1973:62 in Liebenberg 2011: 102).

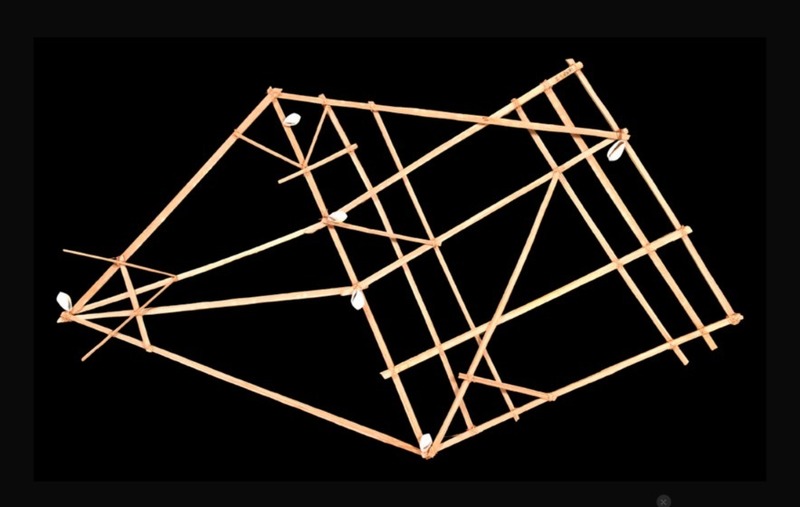

"Early Pacific seafarers did not have scientific instruments or conventional European-style maps to voyage to, and settle, the thousands of islands of Micronesia and Polynesia. Instead they used the movement of the sea, the direction of the wind, the position of the sun and stars, and the flight of birds. This is a navigation chart, obtained by Georg Irmer, the Governor of the Marshall Islands from Chief Nalu of Jaluit atoll in 1896. The strips of wood, bound by cane, represent the currents and winds, and the six small, white shells represent islands" (Pitt Rivers Museum 2007).

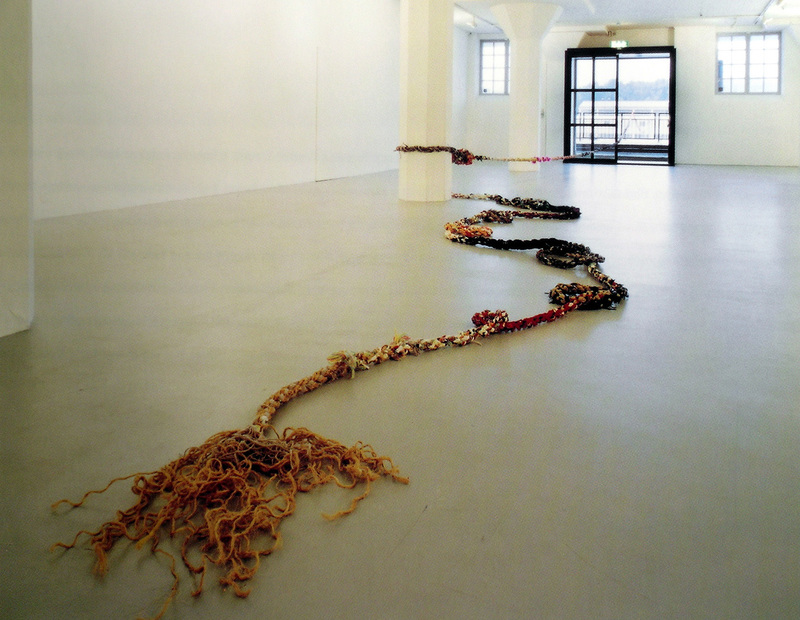

The artist Janine Antoni's installation, Moor (2001), is made from material provided by family and friends. As of 08/18/2009, Moor is 326.9 feet long (99.63 meters). Moor will continue to grow.

In the spring of 1940, Steinbeck and his very close friend, biologist Ed Ricketts, chartered a boat and embarked on a month long marine specimen-collecting expedition in the Gulf of California, which resulted in their collaboration on a book, The Sea of Cortez. Described as both a travelogue and biological record, it reveals the two men's philosophies: it dwells on the place of humans in the environment, the interconnection between single organisms and the larger ecosystem, and the themes of leaving and returning home. A number of ecological concerns, rare in 1940, are voiced, such as an imagined but horrific vision of the long term damage that the Japanese bottom fishing trawlers are doing to the sea bed. Although written as if it were the journal kept by Steinbeck during the voyage, the book is to some extent a work of fiction: the journals are not Steinbeck's, and his wife, who had accompanied him on the trip, is not mentioned (though at one point Steinbeck slips and mentions the matter of food for seven people). Since returning home is a theme throughout the narrative, the inclusion of his wife, a symbol of home, would have dissipated the effect. Steinbeck and Ricketts are never mentioned by name but are amalgamated into the first person "we" who narrate the log.

In Wes Anderson’s 2004 film, The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou, Bill Murray plays the part of eccentric oceanographer, Steve Zissou. Zissou is both a parody of and homage to Jacques-Yves Cousteau, to whom the film is dedicated. The characters were inspired by The Great Gatsby and The Magnificent Ambersons, whilst the plot has been compared to Moby Dick. While filming a documentary, Steve’s partner and close friend, Esteban du Plantier, is eaten by a creature Zissou describes as a “Jaguar shark.” For his next project, Zissou orchestrates documenting the shark’s destruction.

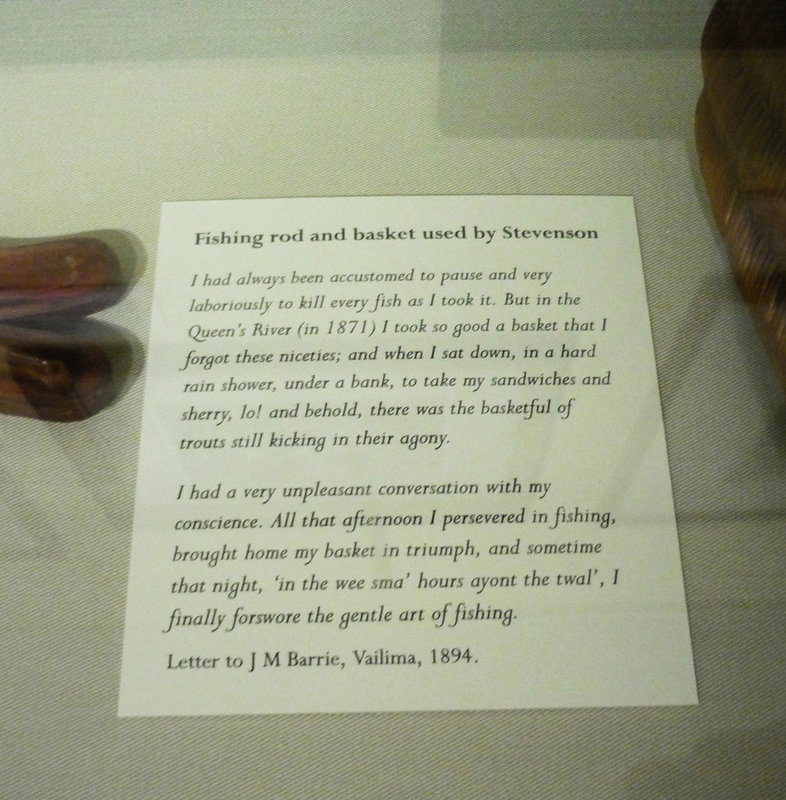

My dear Barrie,

We are pegging out in a very comfortless spot. Hoping this letter may be found and sent to you, I write a word of farewell.... More practically I want you to help my widow and my boy – your godson.

(...)

I am not at all afraid of the end, but sad to miss many a humble pleasure which I had planned for the future on our long marches. I may not have proved a great explorer, but we have done the greatest march ever made and come very near to great success. Goodbye, my dear friend.

Yours ever,

R. Scott.

(Excerpt from letter penned by Scott to Barrie on 29 March 1912)

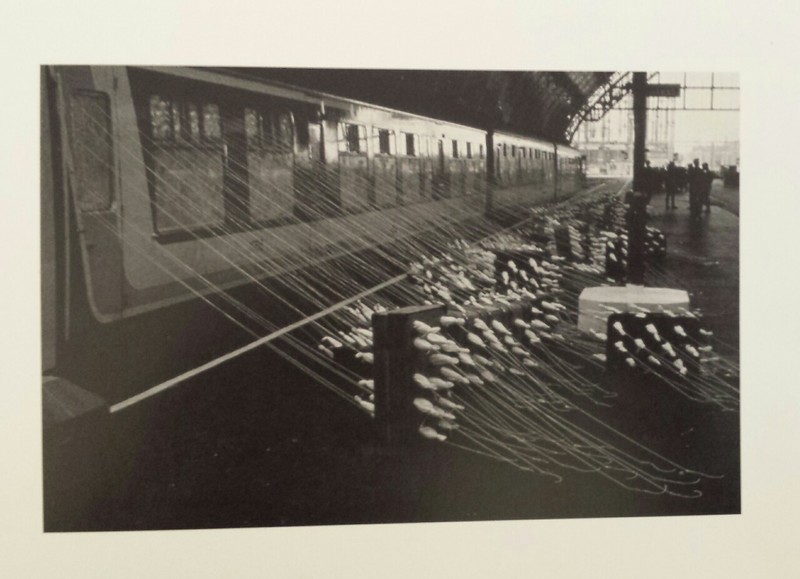

"Just about dusk one day in April 1948 Ed Ricketts stopped work in the laboratory in Cannery Row. He covered his instruments and put away his papers and filing cards. He rolled down the sleeves of his wool shirt and put on the brown coat which was slightly small for him and frayed at the elbows.

He wanted a steak for dinner and he knew just the market in New Monterey where he could get a fine one, well hung and tender. He went out into the street that is officially named Ocean View Avenue and is known as Cannery Row. His old car stood at the gutter, a beat-up sedan. The car was tricky and hard to start. He needed a new one but could not afford it at the expense of other things.

Ed tinkered away at the primer until the ancient rusty motor coughed and broke into a bronchial chatter which indicated that it was running. Ed meshed the jagged gears and moved away up the street.

He turned up the hill where the road crosses the Southern Pacific Railways track. It was almost dark, or rather that kind of mixed light and dark which makes it very difficult to see. Just before the crossing the road takes a sharp climb. Ed shifted to second gear, the noisiest gear, to get up the hill. The sound of his motor and gears blotted out every other sound. A corrugated iron warehouse was on his left, obscuring any sight of the right of way.

The Del Monte Express, the evening train from San Francisco, slipped around from behind the warehouse and crashed into the old car. The cow-catcher buckled in the side of the automobile and pushed and ground and mangled it a hundred yards up the track before the train stopped" (Steinbeck 1951: 279).

After Ricketts' death in 1948, Steinbeck dropped the species catalogue from the earlier The Sea of Cortez and republished it with a eulogy to his friend added as an afterword.

In a short story by the writer Alice Munro titled, Walker Brothers Cowboy, a young girl joins her father, a fox farmer turned traveling salesman, on his visits to homes in the countryside where they live. After observing her father nearly getting doused with a chamber pot of urine by an unwelcoming customer, he veers off his usual rounds to visit a woman whom she slowly understands to be his sweetheart from when he was younger. Driving back home, she thinks about the events of the day:

"So my father drives and my brother watches the road for rabbits and I feel my father's life flowing back from our car in the last of the afternoon, darkening and turning strange, like a landscape that has an enchantment on it, making it kindly, ordinary and familiar while you are looking at it, but changing it, once your back is turned, into something you will never know, with all kinds of weathers, and distances you cannot imagine.

When we get closer to Tuppertown the sky becomes gently overcast, as always, nearly always, on summer evenings by the Lake" (Munro 2010: 23).

Melissa Gould

1991 - 2008

Pier 59

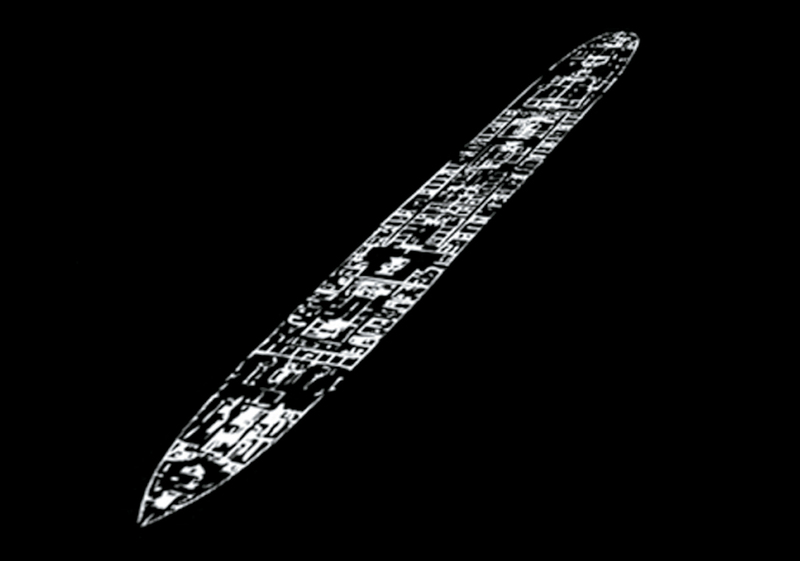

A monumental installation piece recreating the ocean liner Titanic as a floating deck plan (in its original size – 882 feet long; 92 feet wide), projected in light onto the surface of the Hudson River at Pier 59 (due west of West 18th Street), the ship's intended destination in 1912.

A year after Simone's death from cancer, Cousteau announced that he had been having an affair with a woman, Francine Triplet, for over a decade. He also had two children with her, Diane and Pierre-Yves.

These are the thoughts of the protagonist in the last paragraph of John Banville's novel, The Sea: "As I stood there, suddenly, no, not suddenly, but in a sort of driving heave, the whole sea surged, it was not a wave, but a smooth rolling swell that seemed to come up from the deeps, as if something vast down there had stirred itself, and I was lifted briefly and carried a little way toward toward the shore and then set down on my feet as before, as if nothing had happened. And indeed nothing had happened, a momentous nothing, just another of the great world's shrugs of indifference (Banville 2005: 26)

"All that debris still remains under the bridge for the most part, and it has become a dive site. It is a very difficult dive site to get to because of the swiftly moving water and the very short period of slack time.

Nature in this area has just a tremendous ability to take over. You have a man-made structure like the Tacoma Narrow Bridge that collapsed into the water. Very quickly, the ocean took it over and made it part of the habitat".

Extract from the voiceover of trailer for 700 Feet Down (a documentary about the Tacoma Narrows Bridge told through witnesses of the bridge’s 1940 demise as well as intrepid divers exploring a reef of wreckage, ultimately reflecting on how history influences the present)

"Kuhn’s example illustrates how an insider’s view of the laboratory and its equipment poses a threat for discovery because of its entrenched expectations of experimental outcomes and prescribed instrumental functions. The circumstances which enabled Wilhelm Röntgen (who was also an insider) to first notice these new rays (X-rays) are not clear, but in his discussion of this example, Kuhn proposes that the occurrence of anomaly enables discovery, and that Röntgen’s “recognition that nature has somehow violated the paradigm-induced expectations that govern normal science” (1970: 52-3) was important. Kuhn places emphasis on the fact that Röntgen valued the anomaly as opposed to ignoring it – and that this was a vital part of the process of discovery" (Liebenberg 2021: 114).

Marine biologists studying whalesharks use the pattern-recognition technique, developed in 1986, that astronomers use to analyze data from the Hubble Space Telescope. Studying the spatial relationships between a whaleshark's spots form the basis for creating a unique identifier for each shark.

In addition to being able to identify each shark by its spots, Conservation International scientists in Indonesia performed a first in 2015, attaching satellite transmitters to the dorsal fins of whale sharks. In doing so, they were able to track their migratory movements and diving behavior over a 27 month period.

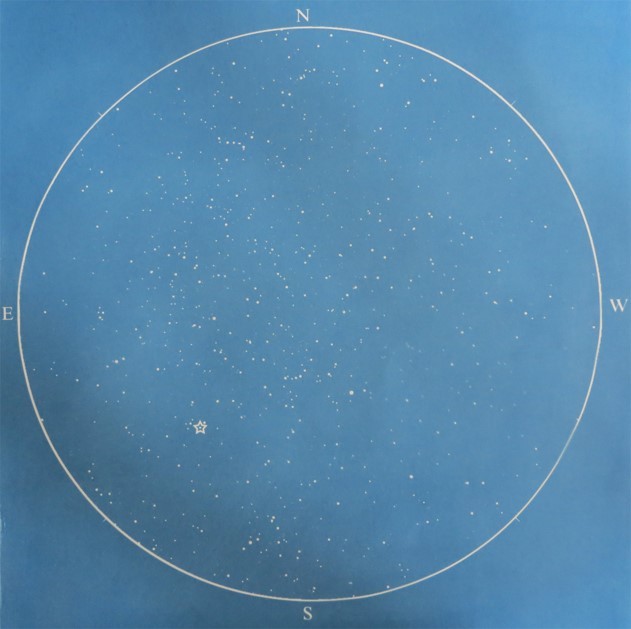

The work shows the exact positioning of the stars from J.M. Barrie’s window at 3 Adelphi Terrace, London (51°30'N 0°7'21"W), on Saturday, 19 June 1937 – the night of his death. Based on the direction of his window, I was able to locate the ‘second star to the right’ at the 45 degree angle he would have stood and viewed the night sky. Hopefully, he reached his destination, after departing the flat and traveling ‘straight on till morning’.

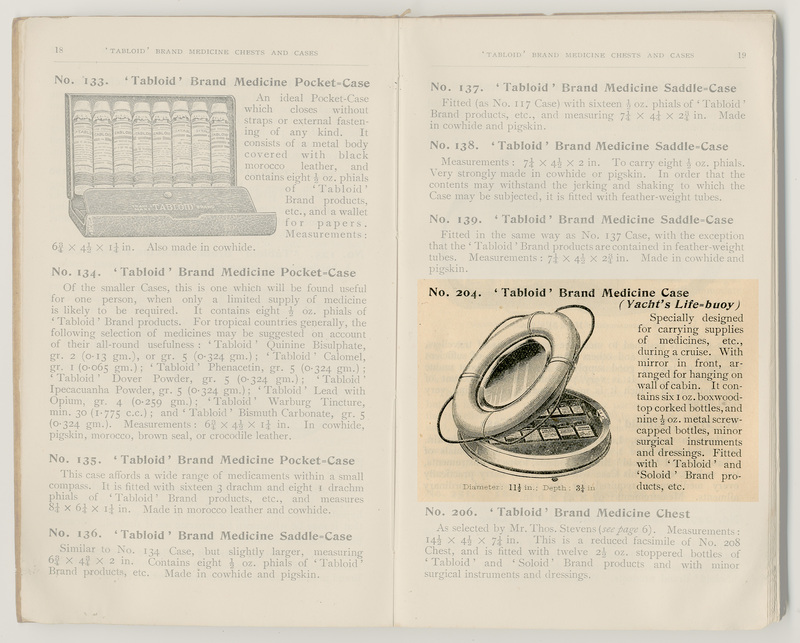

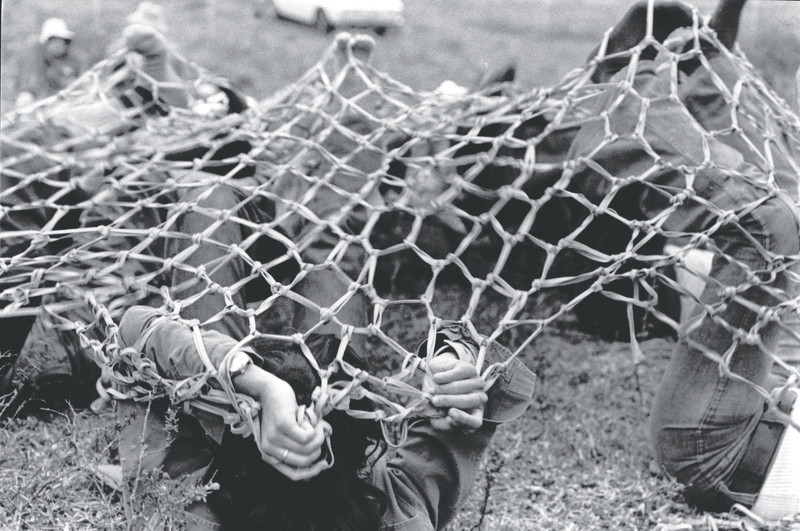

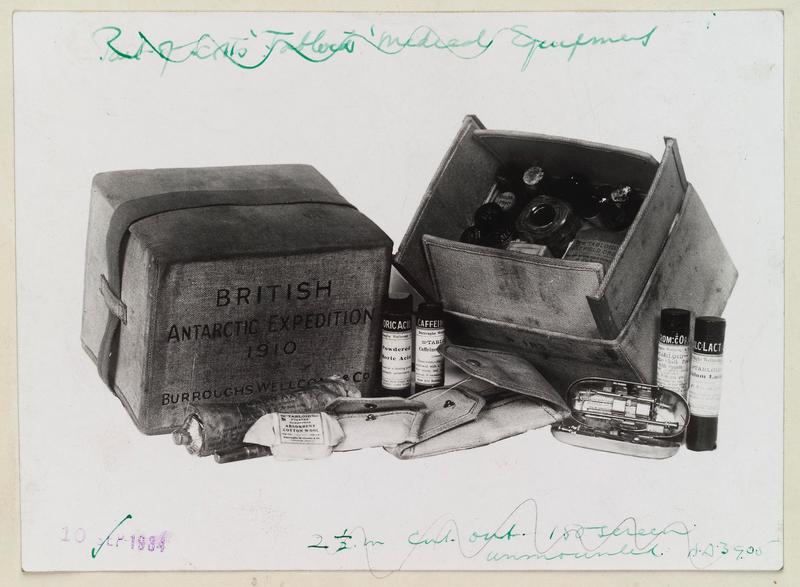

The expedition carried with them a Tabloid Medicine Chest. On the 11th of March, knowing that the party was unlikely to survive, Scott ordered Edward Wilson, the expedition’s Chief Scientist and a qualified doctor, to divide the painkillers between them so they could each end their life on their own terms. Writing in his diary on that day, Scott states, “I practically ordered Wilson to hand over the means of ending our troubles to us, so that anyone of us may know how to do so".

Scott, Bowers and Oates had thirty opium tabloids apiece and Wilson, the morphine. Scotts diary entry on either the 22nd or 23rd of March showed that they had a change of heart however: “no fuel and only one or two left of food — must be near the end. Have decided that it shall be natural — we shall march for the depot with or without our effects and die in our tracks".