-

Visually categorising a selection of my research material (accumulated since 2015).

-

The researcher who conducted this study and wrote the dissertation, 'The Virus and the Vaccine: Curatorship and the Disciplinary Outsider '(2021).

-

In 2012, while exploring possible curatorial opportunities for the Honours in Curatorship students, I met with Sven Ouzman, a curator in the archeology department at Iziko, to chat about possible opportunities pertaining to this collection. I took him the newly designed course prospectus, to peruse. He flipped through it and when he got to the second last page, he paused. ‘Do you know the story behind this image’, he asked. I told him I didn’t…

He pointed at the rock in the bottom right hand corner and started his story. Apparently this rock was not part of the SAN Rock art collection at all. It belonged to an archeologist who worked at the museum for close to twenty years. When she first started at the museum, her partner, now husband (and also an archeologist) also worked there with her. They were still in the beginning of their relationship and he was, to use older terminology, still courting her. One of the gifts he gave her during this period, was a rock he drew that mimicked San rock paintings, probably ones that would pertain to love in some way or other. She kept this in her office and, when she finally left the museum and had to empty her belongings, forgot to pack the rock as well. Exit archeologist, enter the lady who tidied the office before the new occupant moved in. On finding the rock she assumed it was part of the collection and returned it to the store room where it was assimilated into the bona fide rock art collection.

I don’t know in how many exhibitions it subsequently appeared, but in 2010 it appeared up in Pippa Skotnes’s exhibition 'Made in translation' – an exhibition that fittingly explored ways in which translations from the landscape have been made and in so doing, placed images of rock art in the context of other forms of translation.

-

"This cabinet displayed a round-bottomed flask that broke during the installation of the exhibition, and which I attempted to mend. The accompanying BWC medicine chest manual highlights the qualities the company wanted to portray as unique to the Tabloid medicine chest and that they believed would set them apart from competitors – such as the longevity of the medicines they sold and the indestructability of the chests (BWC 1925: 2–3).

Addressing the supposed indestructability of the chest by focusing specifically on the wide array of glass-stoppered bottles that form a large part of its overall contents and which, according to BWC, ensured the longevity of the medicines, this exhibit displayed a laboratory bottle of similar material, but in a state that demonstrates its fragility. As such, it subverts BWC’s grand claims of indestructability and thereby throws the rest of its claims into doubt" (Liebenberg 2021: 259).

-

"Undergraduate students regularly engage in discussions around certain displays as part of their teaching programme (N. Zachariou, personal communication, 27 May 2020), and the installation is also used to introduce visitors (exchange students and school children, for example) or students from other UCT departments (architecture students taking the archaeology module) to the department and the discipline (J. Parkington, personal communication, 20 June 2020). It has even been described as a ‘super curriculum’ (or as ‘several super curriculums’) for how it visualises what archaeology does on both an empirical and procedural level (J. Parkington, personal communication, 20 June 2020)" (Liebenberg 2021: 210).

-

"In 1993, the [Lydenberg] heads were temporarily moved from the SAM stairs into the SANG as part of Payne’s exhibition. In the gallery context, where ‘the shifting definitions of art, the meaning of objects, the contexts of spaces as well as the politics of culture are continuously examined’ (Martin in Payne 1993: 4), these objects became part of an exhibition of Payne’s own terracotta heads, painted and sculpted cases, etchings inspired by the heads, drawings and a collection of supermarket trolleys" (Liebenberg 2021: 159 - 160).

-

A student model of the ‘Villus of the small intestine wall’ found in the workshop of the Anatomy Building, UCT.

-

"By positioning artefacts to emphasise their labelling (stones are positioned to reveal the details written on them), including seemingly familiar objects and expanding and shrinking timelines, the installation [Division of the World] draws attention to the framing devices, tools and methods of the department’s insiders" (Liebenberg 2021: 207).

-

A variety of pottery shards of Asian porcelain, European earthenware and British stoneware in a drawer in the Department of Archaeology, UCT.

-

An example from demonline (UCT Physics Department’s website with descriptions of educational demonstrations). Its description reads: ‘A lodestone is suspended by a string. Show that it rotates on bringing a magnet near it. Dip it into iron filings and show that it picks them up.’

-

"The chest was featured in a work titled 'Hoard', for which Bloch sculpted in clay the objects in the UCT collection as well as ones from the 11th century Mapungubwe collection (housed at the University of Pretoria). She painted these sculpted objects gold and presented them in museum display cases, drawing attention to the arbitrary nature of objects’ value and to the possibility that historically loaded items can be accidentally overlooked and misevaluated (Bloch in Honigman 2014: online)" (Liebenberg 2021: 82 - 84).

-

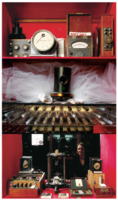

"Strategies such as juxtapositioning also served to highlight poetic and emotive qualities in fields not known for encouraging them, as in a cabinet curated by Langerman titled Capitance. This featured a range of instruments from the Physics department used to measure electrical currents (galvanometers, capacitors and Wheatstone bridges); a crystal goniometer measuring crystal face angles and crystal 175 from the crystal collection in Geological Sciences; M.R. Drennan’s models of the human embryo and a wax model of flesh; and a white tutu from the School of Ballet. In combining this selection of scientific instruments with a tutu, Langerman made allowance for the materials to be considered in a more poetic light, inviting the viewer to consider how a grand jeté defies the laws of physics, for example" (Liebenberg 2021: 186).

-

"In 'Similitude', Langerman brought together a selection of objects from three disparate disciplines – glassware from chemical engineering; a skull with an arrow embedded in it and a torch used as a murder weapon from forensic pathology; and two flutes from the Kirby collection. Ignoring the assigned functions the objects performed within their respective disciplines, she chose instead to use their formal characteristics as a taxonomic device. They were all, as she described them, ‘long thin things’ (Langerman n.d.). In displacing these objects from their respective disciplines and positioning them in proximity to objects that shared this new category, she neutralised their disciplinary functions and flattened their meanings within those fields (Langerman n.d.)" (Liebenberg 2021: 183).

-

"The large quantity of papers in the BC666 collection pertaining to dental matters – which includes ‘legal and financial papers of the dental practice, papers of the various dental societies to which Walter belonged from 1905 to 1934’ and letters on various dental matters, as well as a large section devoted to correspondence, memoranda and notes on the Medical, Dental and Pharmacy Act of 1928 – shows he was ‘very active in dental politics’ (Hart & Lydall 1981: 1). As an 'office-bearing member of the Dental Society of the Cape Province, and a member of the South African Dental Association, he was the key figure in formulating and presenting the dentists’ case against unqualified dental mechanics in the proposed new medical bill, which was passed in 1928 as the Medical, Dental and Pharmacy Act' (Hart & Lydall 1981: 1).

This act was considered a milestone in the development of organised medical, dental and pharmaceutical practices in South Africa, establishing a single set of regulations for these professions across the country (Ryan 1986: 149–151). It was also, however, one of a series of laws passed in South Africa that have regulated indigenous medical practices since the 19th century. Legislation passed in 1862 prevented sangomas from practicing (Paarl in Bishop 2010: 14), and the 1928 act barred inyangas from practicing in all parts of the country except Natal, where they could continue to practice if granted a license (Flint in Bishop 2010: 14–15). The act also banned the indigenous use of ‘European’ methods of diagnosis and treatment, for example forbidding the use of stethoscopes by inyangas (Bishop 2010: 16)" (Liebenberg 2021: 53 - 55).

-

Educational models found in the Anatomy workshop:

"Borrowing from Herbert Read’s art historical discussion on looking, Digby posits that the biomedical practitioner’s generally critical attitudes were shaped in part by their limited recognition of indigenous medicine during this period – ‘what we see is inseparable from how we see; the eye is not innocent, and vision is partial’ (Digby 2006: 356) and, quoting Read, ‘we see what we learn to see, and vision becomes a habit, a convention, a partial selection of all there is to see’ (in Digby 2006: 356). Accordingly, Digby argues that the Western practitioners would have had, at best, only a partial view of the different medical systems in South Africa during this period (Digby 2006: 357) and probably only to the extent that it was a threat to their own livelihood and authority – as evidenced in the 1928 Medical, Dental and Pharmacy Act that Floyd helped instate" (Liebenberg 2021: 55).

-

Examples of Wellcome's design changes annotated on tracing paper. 1914–1938. WF/M/I/PR/O01/3, 4, 9, 8. Wellcome Collection.

-

A drawing by the artist-curator James Hutchinson (Chapter Thirteen) based on an audio description of the object as art of the Glasgow International Arts festival.

"Nina Liebenberg also undertakes a form of object analysis at an institutional border. She spent an afternoon in the strongroom of the University of Cape Town's special collections department, examining an early 20th century medicine box commissioned for a hunting trip in (then) Northern Rhodesia. Such boxes had been essential parts of the British colonial project, and allowed emigres, missionaries and explorers to venture deeper into unknown territory without fear of contracting tropical diseases. Liebenberg’s report from the strongroom acts as a set of instructions for The Landis Museum’s curator to make a drawing of the box, to which he has no physical access".

Extract from the 'Exhibition Guide' of the Landis Museum (Chapter Thirteen), Glasgow International Arts Festival, 20 April - 07 May 2018.

-

"In Simon Starling’s work, inanimate objects are activated in various ways, especially when their political or economic history is revealed or when their materiality becomes an embodiment of something discovered during his research. His work enables and celebrates diverse interpretations of objects in many instances, as Greenblatt (1991) notes when referring to artistic and curatorial activity, deflecting attention away from the object onto the systems that gave rise to it in the first place. Starling conducts a close inspection of his objects, usually following a web of connections across the globe and across history, which in many of his works lead him back to the starting point; a vintage photograph of a Henry Moore sculpture leads to the production of a bronze sculpture based on the shape of a single enlarged silver particle that makes up the photograph and which, when converted into a sculpture, resembles the biomorphic shapes that served as inspiration for the Moore sculpture in the original vintage photograph ('Silver particle/bronze (after Henry Moore)', 2008). The machinations of its history somehow lost in the image when seen in the museum archive come back into play through the translations and reconstructions encountered in the detour and are materialised in the exhibition format" (Liebenberg 2021: 26 - 28).

-

"The caption for the image offered further information about the department in which the medicine chest was located, stating: ‘Black metal travelling medicine chest, containing bottles and packets of medication belonging to Walter Floyd, given to UCT by the Floyd family (Manuscripts and Archives).’

It seemed strange to me that this three-dimensional object would be housed in the Manuscripts and Archives (M&A) department (also known as ‘Special Collections’) of UCT Library, as it hosts collections of ‘printed and audio-visual materials on African studies and a wide array of other specialised subjects, as well as over 1,300 sub-collections of unique manuscripts and personal papers’ (Special Collections 2015). As my italics emphasise, bulkier three-dimensional objects seemed to have no place here.

I nonetheless thought it worthwhile to type the words ‘medicine chest’ into the general library search engine, an application called Ex Libris Primo; the search delivered no results" (Liebenberg 2021: 24).

-

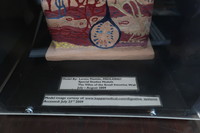

Hiddingh Hall during the construction of the installation of Curiosity CLXXV.

-

"Along with the guides that regulated practices and protocols to stabilise and standardise an individual’s response to unfamiliar and disorienting sights (Kennedy 2013: 42), the gender, class and ethnicity of the observer were also of importance , as was the use of ‘ever more sophisticated instruments and calculations designed to minimize the intrusion of subjectivity into the reporting of information’ (Driver 2001: 55). By regulating who was doing the viewing, stipulating what should be viewed and how and supplying tools to measure these observations, scientific institutions promoted an authoritative ‘way of seeing’ in the field that differentiated the scientific view from that of the ordinary traveller (Driver 2001: 49)" (Liebenberg 2021: 109).

-

An extract from an email from archaeologist and former head of African Studies, Prof Nick Shepherd (Jan 21, 2021, 11:33 AM):

"Disciplinary practices and regimes of care constitute a kind of bureaucratization or governmentality of elapsed time and its material remains and human relationships, placing these remains and relationships under a kind of administration. We think of the elaborate structure of regional typologies and chronologies, the immense work of correctly assigning artefacts and sites to these imagined categories, and the vast institutional apparatus that supports these endeavors – all of which constitute archaeology as a formidable disciplinary enterprise. In the face of this enterprise, the 'many worlds' of local claims to the past have little chance of success."

-

"The processes of digression and diversion have much in common with what the writer Ross Chambers (1999) calls ‘loiterature’. Chambers investigates the digressive, category-blurring genre of writing found in works such as Nicholson Baker’s 'The mezzanine', Paul Auster’s 'City of glass' and Laurence Sterne’s 'Tristam Shandy'. Loiterly writing, according to Chambers, disarms criticism by providing a moving target, shifting as its own divided attention constantly shifts.

Criticism depends on the opportunity to discriminate and hierarchise, determining what is central and what is peripheral (Chambers 1999: 9), which this form eludes by resisting contextualisation or singular categorisation. Loiterature promotes sites of endless intersection, where attention is always divided between one thing and some other thing, always willing and able to be distracted, contrasting ‘the disciplined and the orderly, the hierarchical and the stable, the methodical and the systematic’ (Chambers 1999: 10).

In contrast to methods of science that seek to stabilise objects within taxonomic systems or that require the formulation of hypotheses to provide direction for experimentation and a basis for concrete outcomes, the processes of curatorship and artmaking revel in rerouting and redirecting and in diversion and digression" (Liebenberg 2021: 286).

-

The wall text accompanying these charts in the Hunterian museum, Glasgow, reads: "In the late 19th and 20th centuries, before the advent of colour slides that could be projected, the teaching of Zoology depended heavily on the use of wall charts to illustrate lectures. They were hung on a special pulley system at the front of the lecture theatre and, because of their large size, could be clearly seen from the back of the class".

-

In 'Resonance and Wonder' Greenblatt discusses ‘resonant’ moments in regards to museum displays as “those in which the supposedly contextual objects take on a life of their own and make a claim that rivals that of the object that is formally privileged. A table, a chair, a map – often seemingly placed only to provide a decorative setting for a grand work – become oddly expressive, significant not as a background but as compelling representational practices in themselves. These practices may in turn impinge on the grand work, so that we begin to glimpse a kind of circulation: the cultural practice and social energy implicit in mapmaking is drawn into the aesthetic orbit of a painting, which has itself enabled us to register some of the representational significance of the map” (1991: 22- 23). For him a resonant exhibition often “pulls the viewer away from the celebration of isolated objects and toward a series of implied, only half-visible relationships and questions” (1991: 23).

-

Image from page 137 of the 'Curiosity CLXXV' catalogue, describing resonance and its application in MRI technology.

-

Etching from Giovanni Battista Piranesi's 'Carceri d'invenzione (Imaginary Prisons)' ca. 1749–50

-

Etching from Giovanni Battista Piranesi's 'Carceri d'invenzione (Imaginary Prisons)' ca. 1749–50

-

Woodburytype

-

Woodburytype

-

A detail from the wallpaper used outside the Cape Town Diamond Museum in the V&A Waterfront.

-

Etching from Giovanni Battista Piranesi's 'Carceri d'invenzione (Imaginary Prisons)' ca. 1749-50

-

Plate from Williams, G. 1902. 'The Diamond Mines of South Africa: Some Account of their Rise and Development'. New York, London: Macmillan.

-

In 2008, the exhibition 'Unconquerable Spirit: George Stow and the landscapes of the San' opened at the Iziko Museum of South Africa. Curated by Pippa Skotnes, the exhibition featured the work of a relatively unknown figure in 19th century South African history. George William Stow was a British born, South African geologist, ethnologist, poet, historian, artist, cartographer, and writer who was responsible for a creating large collection of watercolours and drawings that documented the rock art he found in the caves and shelters of South Africa. The exhibition brought together a vast range of materials representing Stow’s life and the period in which it was produced – from his drawings and paintings; his letters, documents, and poems; to his maps, and field diaries.

The display shows one map in particular which is kept as part of the National Library of South Africa collections, and was drawn by Stow during the period he was conducting geological surveys of the country surrounding the diamond fields of Kimberley, down to the junction of the Orange and Vaal rivers and beyond. It shows amongst other things, the diamondiferous deposits of the Vaal river during the late 19th century and, as part of this section of the exhibition which focused on Stow the geologist, Skotnes displayed it alongside relevant disciplinary materials she sourced from the Department of Geological Sciences, University of Cape Town.

-

"Stow’s discovery of coal deposits in 1878, found in the beds of the Vaal River, was of interest to the diamond magnate, Sammy Marks. Marks realised the importance of Stow’s discovery and the opportunity for using coal at the Kimberley diamond fields for energy generation (Leigh, 1968:112). He believed he could transport the coal from Vereeniging to Kimberley by floating it down-river by a series of weirs to his diamond claims. This turned out to be impractical and he had to resort to using ox-wagons as a method of transport instead (Leigh 1968:17).

Marks & Lewis who at that time owned a quarter of all the Kimberley diamond claims, sold most of their Kimberley claims to concentrate on the coal finds through their newly formed mining company, the Zuid-Afrikaansche en Oranje Vrystaatsche Mineralen en Mijnbouvereeniging (later to become the Vereeniging Estates Limited). In 1892, the small village of Vereeniging was formally established" (Liebenberg 2021).

-

Geological Map of the Vaal River, from Fourteen Streams to the Kareyn Poort shewing the Various Formations, and the Positions of the Diamantiferous Deposits. Sheet No 11'.

-

In the exhibition, 'Chest: a botanical ecology', "this cabinet extended the ideas of fragility and fallibility represented by the broken glass laboratory bottle, displaying four ‘breath sculptures’ made by the five individual breaths of children who suffer from asthma: Thaakira Salie (aged 8), Ziyaad Small (aged 10), Blake Leppan (aged 9) and Jessie Allot (aged 11). Working in collaboration with the Allergy Foundation of South Africa and Andre de Jager, UCT’s resident glass blower in the Department of Chemistry, I facilitated a workshop in which the children were taught the practice of blowing glass and then produced their own sculptures by breathing into molten glass. The breath sculptures made by these children were far removed from the functional bespoke glassware usually produced in the workshop for chemical experiments or for those conducted for physics and chemical engineering (A. de Jager, personal communication, 20 August 2018)" (Liebenberg 2021: 263).

-

Chromogenic color print

-

Household objects and spray paint.

A space station made with objects found around the house, spray-painted with white enamel and suspended from the ceiling with monofilament.

-

A wounded post-mortem ledger

-

In Kurt Vonnegut's 'Slaughterhouse-Five', the protagonist Billy, is abducted by aliens and taken to their planet, Tralfamadore. Throughout the novel, Billy imparts what he has learned from the Tralfamadorians, whilst there. In one instance, in a letter to a late night radio station, he writes about their views on time:

"The most important thing I learned on Tralfamadore was that when a person dies he only appears to die. He is still very much alive in the past, so it is very silly for people to cry at his funeral. All moments, past, present, and future, always have existed, always will exist. The Tralfamadorians can look at all the different moments just the way we can look at a stretch of the Rocky Mountains, for instance. They can see how permanent all the moments are, and they can look at any moment that interests them. It is just an illusion we have here on Earth that one moment follows another one, like beads in a string, and that once a moment is gone it is gone forever. When a Tralfamadorian sees a corpse, all he thinks is that the dead person is in a bad condition in that particular moment, but that the same person is just fine in plenty of other moments. Now, when I myself hear that someone is dead, I simply shrug and say what the Tralfamadorians say about dead people, which is 'So it goes' " (Vonnegut 1969: 24 - 25).

-

-

The Japanese have a word, ‘ma’, for this interval which gives shape to the whole – this ‘gap’, ‘opening’, ‘space between’ or ‘time between’. Ma is not something that is created by compositional elements, rather it can be understood as the thing that takes place in the imagination of the human who experiences these elements. A room, for example, is called 'ma', as it refers to the space between the walls. Or a rest in music, which indicates a pause between the notes or sounds (Pilgrim 1986: 255).

-

Screengrab of an image search, typing in 'third wave'

-

Vaal river mud on paper

-

The train crossing the Vaal bridge in the picture was the funeral train of Paul Kruger, the former president of the ZAR. He died in 1904 in Switzerland and his remains were taken to Pretoria.

-

This object, a leather cartridge case said to belong to Sammy Marks, occupies a place in the Special Collections of the University of Cape Town. It forms part of the Sammy Marks Papers (BC770).

-

The predominantly black community of Sharpeville was established near Vereeniging. On the 21st of March, 68 years after Vereeniging was first established, the Sharpeville massacre occurred.

-

Woodburytype

-

'Devils Bridge' sketched by Lister on his travels through Europe showing a bridge crossing the Gotthard Pass, northern approach, Switzerland.

The term 'devil's bridge' is applied to many ancient bridges found primarily in Europe. These were stone or masonry arch bridges and, because they represented a significant technological achievement in ancient architecture, were objects of fascination and stories. The most popular of these featured the Devil, either as the builder of the bridge (relating to the precariousness or impossibility of such a bridge to last or exist in the first place) or as a pact-maker (sharing the necessary knowledge to build the bridge, usually in exchange for the communities souls). The legend attached to the bridge sketched by Lister is of the latter, and was related by Johann Jakob Scheuchzer in 1716.

According to Scheuchzer, the people of Uri recruited the Devil for the difficult task of building the bridge. In return for his expertise, the Devil requested the soul of the first thing to pass the bridge. To trick the Devil, the people of Uri sent across a dog by throwing a piece of bread, and the dog was promptly torn to pieces by the Devil.

Reference: Scheuchzer, J. , 1747 [1716]. Naturgeschichte des Schweitzerlandes. Vol. 2: 94.