Items

keywords is exactly

colonialism

-

Eucalyptus

"The plants [dislayed in this cabinet] were bought from the Adderley Street flower market in central Cape Town and are used by the sellers for medicinal purposes to treat chest and respiratory problems, with the leaves of the eucalyptus added to a bath and those of the protea infused in hot water and drunk as a broth. The flower sellers trading in Trafalgar Place and along Adderley Street have been doing so since at least the mid-1880s but became viewed as threats to the local flora by the European settlers at about the same time the medicine chest was first introduced to the city at the beginning of the 20th century. The settlers initially preferred to cultivate plants imported from their home countries to indigenous varieties, introducing many species to South Africa for nostalgic or practical reasons (subsequently problematic for local biodiversity) (Van Sittert 2002: 103). In the wake of emerging white nationalism in the 1890s, interest in indigenous plants gained momentum and was deployed to create a sense of belonging to the ‘foreign’ land (Boehi 2013: 133). A botanical discourse was mobilised to underscore ideas about identity and belonging, such as ‘roots’ and ‘ideas of rootedness’, and laws regulating flower picking (which usually occurred on the mountain) were passed in this period and were secured by the Wild Flower Protections Act in 1905 and an amendment thereto in 1908 (Boehi 2013: 133)"(Liebenberg 2021: 275). -

Proteas

"The plants [dislayed in this cabinet] were bought from the Adderley Street flower market in central Cape Town and are used by the sellers for medicinal purposes to treat chest and respiratory problems, with the leaves of the eucalyptus added to a bath and those of the protea infused in hot water and drunk as a broth. The flower sellers trading in Trafalgar Place and along Adderley Street have been doing so since at least the mid-1880s but became viewed as threats to the local flora by the European settlers at about the same time the medicine chest was first introduced to the city at the beginning of the 20th century. The settlers initially preferred to cultivate plants imported from their home countries to indigenous varieties, introducing many species to South Africa for nostalgic or practical reasons (subsequently problematic for local biodiversity) (Van Sittert 2002: 103). In the wake of emerging white nationalism in the 1890s, interest in indigenous plants gained momentum and was deployed to create a sense of belonging to the ‘foreign’ land (Boehi 2013: 133). A botanical discourse was mobilised to underscore ideas about identity and belonging, such as ‘roots’ and ‘ideas of rootedness’, and laws regulating flower picking (which usually occurred on the mountain) were passed in this period and were secured by the Wild Flower Protections Act in 1905 and an amendment thereto in 1908 (Boehi 2013: 133)" (Liebenberg 2021: 275). -

Livingstone

A small wooden chip from the same object collection as the medicine chest balanced on top of one of the bottles from the chest. "The treatment, the Livingstone rouser, was formulated by Dr Livingstone, who, after an attack of malaria in 1853, patented this mixture of quinine and purgatives (calomel, rhubarb and jalop) mixed with opium (Barrett & Giordani 2017: 1655–1666). The chip balanced on its lid is said to be from the almond tree under which he proposed to Mary Moffat in 1844. The juxtaposition of these two objects, one representing the quantifiable and the other the poetic, draws the viewer to consider the conflation of these two realms" (Liebenberg 2021: 273). -

A 'Jungle'

"A ‘jungle’ consisted of a selection of pathological specimens from the Pathology Learning Centre that had been affected by typhoid fever, ascaris adult worms, yellow fever, amoebic ulcerations, tuberculosis and malaria. The diseases that afflicted these specimens were regarded as ‘tropical’. As described in Chapter One, BWC used the jungle as a significant terrain that called for a medicine chest to combat pathogens: ‘Whether you were valiantly saving your compatriot in war, traversing a dark African jungle, navigating one of the world’s first flying machines, exploring the most desolate place on earth, ascending the highest mountain in the world, or simply enjoying the windswept British coast, the chest would be there, ready for any ailment’ (Johnson 2008b: 255). BWC promoted their chests as the ideal antidote for a tropical landscape ‘at once full of potential wealth for imperial Britain, but simultaneously rife with disease’ (Johnson 2008b: 258) and claimed that the tropical colonies were ‘by far the most dangerous regions for travellers’ (BWC 1934: 8). It was here that ‘desolating ailments’ were encountered, all ‘particularly fatal to the so-called white man who originates in temperate climates’ (BWC 1934: 8). I adapted the colour of the images of afflicted intestines, livers, stomachs and brains and used them as material to construct a dense jungle that referenced this aspect of the medicine chest’s history. Printed on separate glass sections that fit into the cabinet at spaced intervals to create an illusion of depth and three-dimensionality, the work draws on the cross-sectional display technique used in many anatomy museums worldwide, in projects such as the Visible Human Project (1995) and that the artist Damien Hirst references in his works . Creating a visual link between the UCT specimens and the history of these diseases surfaces the occluded racial undertones of these understandings" (Liebenberg 2021: 267). -

Isigubu through Gqom

"In 2018, the Zulu drum alleged to have been played during the 1906 Bambatha rebellion against British rule and unfair taxation in the colony of Natal (discussed by Nixon) became the focus of Amogelang Maledu’s Honours research project. In ‘Isigubu through gqom: The sound of defiance and Black joy’, Maledu (who has an undergraduate degree in Anthropology and Visual Culture) used the drum’s history of colonial resistance and contextualised it through the contemporary musical genre of gqom, showing music as both an act and celebration of joy and freedom and of defiance against the limitations of township life. Through her ‘speculative and imagined interconnectedness’ of the isigubu and gqom, Maledu appropriated the limited information available about the former and expanded it by reinventing new historical pathways that reframed colonial narrations and aesthetics (Maledu 2018: 29–30). Her curation broke the silence of the Kirby instruments and liberated the isigubu from its ethnomusicological framework through a juxtaposition that spoke back to history and the contemporary moment. In addition, a website provides a framework for historicising gqom and encouraged the growth of its archive through viewer engagement, also highlighting the speculative and stagnant colonial archive in which the isigubu is situated (Maledu 2018: 29–30)" (Liebenberg 2021: 211 - 212). -

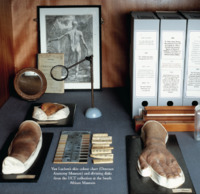

Page 79 of the Curiosity CLXXV catalogue.

"Created by Felix von Luschan, an Austrian doctor, anthropologist, explorer, archaeologist and ethnographer in the early 20th century, the chart, known as the Von Luschan chromatic scale (...) was used to classify skin colour and featured as a tool in race studies and anthropometry of the time. Forgotten by its current department staff and students, its presence draws attention to the role of medicine and science in the apartheid agenda and to the larger racist scientific practices of measuring and classifying human physical differences in the 19th and 20th centuries to produce a ‘typology of race’ (Sturken & Cartwright 2018: 351–352). To support such theories, object collections in scientific university departments worldwide also featured collections of human remains; tools for measuring the size and shape of skulls; and charts detailing various physiognomic features (Sturken & Cartwright 2018: 351 – 352)" (Liebenberg 2021: 122 - 125). -

‘Mrs Glover attending to an ill African chief.’

"The figure of ‘Mrs Glover’, kneeling and treating what appears to be a very ill man, exudes not only the authority of Western medicine within the local context but conveys her as the self-sacrificing and caring European ‘civilizer’ in service of expanding the empire, ‘the medicine chest conveniently by her side’ (Johnson 2008b: 259)" (Liebenberg 2021: 63 - 65). -

Hoard

"The chest was featured in a work titled 'Hoard', for which Bloch sculpted in clay the objects in the UCT collection as well as ones from the 11th century Mapungubwe collection (housed at the University of Pretoria). She painted these sculpted objects gold and presented them in museum display cases, drawing attention to the arbitrary nature of objects’ value and to the possibility that historically loaded items can be accidentally overlooked and misevaluated (Bloch in Honigman 2014: online)" (Liebenberg 2021: 82 - 84). -

A teeth mould guide

"The large quantity of papers in the BC666 collection pertaining to dental matters – which includes ‘legal and financial papers of the dental practice, papers of the various dental societies to which Walter belonged from 1905 to 1934’ and letters on various dental matters, as well as a large section devoted to correspondence, memoranda and notes on the Medical, Dental and Pharmacy Act of 1928 – shows he was ‘very active in dental politics’ (Hart & Lydall 1981: 1). As an 'office-bearing member of the Dental Society of the Cape Province, and a member of the South African Dental Association, he was the key figure in formulating and presenting the dentists’ case against unqualified dental mechanics in the proposed new medical bill, which was passed in 1928 as the Medical, Dental and Pharmacy Act' (Hart & Lydall 1981: 1). This act was considered a milestone in the development of organised medical, dental and pharmaceutical practices in South Africa, establishing a single set of regulations for these professions across the country (Ryan 1986: 149–151). It was also, however, one of a series of laws passed in South Africa that have regulated indigenous medical practices since the 19th century. Legislation passed in 1862 prevented sangomas from practicing (Paarl in Bishop 2010: 14), and the 1928 act barred inyangas from practicing in all parts of the country except Natal, where they could continue to practice if granted a license (Flint in Bishop 2010: 14–15). The act also banned the indigenous use of ‘European’ methods of diagnosis and treatment, for example forbidding the use of stethoscopes by inyangas (Bishop 2010: 16)" (Liebenberg 2021: 53 - 55). -

Clivia's in Kirstenbosch

Part of the ‘Useful plants’ section at Kirstenbosch National Botanical Garden. -

The Landis Museum

A drawing by the artist-curator James Hutchinson (Chapter Thirteen) based on an audio description of the object as art of the Glasgow International Arts festival. "Nina Liebenberg also undertakes a form of object analysis at an institutional border. She spent an afternoon in the strongroom of the University of Cape Town's special collections department, examining an early 20th century medicine box commissioned for a hunting trip in (then) Northern Rhodesia. Such boxes had been essential parts of the British colonial project, and allowed emigres, missionaries and explorers to venture deeper into unknown territory without fear of contracting tropical diseases. Liebenberg’s report from the strongroom acts as a set of instructions for The Landis Museum’s curator to make a drawing of the box, to which he has no physical access". Extract from the 'Exhibition Guide' of the Landis Museum (Chapter Thirteen), Glasgow International Arts Festival, 20 April - 07 May 2018. -

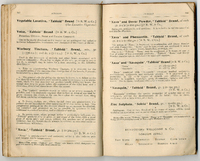

BC666

A page of the Tabloid guide. -

Haematite Miner's Lung (Or Sidero-silicosis)

Catalogue No: R3-d55-0331. Origin: UCT Anat Path museum. Old Museum No: V:x:6. Year: not recorded. Clinical data: No further clinical or laboratory details are available other than that the patient was an emaciated 50 year old man. Macroscopy: The specimens preserved are both lungs, the heart, kidneys, spleen and and portions of liver. In the thorax, both pleural cavities were completely obliterated by a fibrous pleurisy of long-standing and both lungs were universally adherent throughout. They were stripped off with difficulty and were found to have thickening of the pleura over the upper lobe on the left side and the upper and middle lobes on the right. The lower lobes on both sides were soft and spongy while the upper lobes were dense and firm on palpation but on section there was no cavitation and no evidence of tuberculosis. The left lung showed a dense fibrosis of the whole of the upper lobe and the upper third of the lower lobe; no crepitant lung tissue could be found in the upper lobe while the lower two-thirds of the lower was crepitant and showed emphysema of a hypertrophic nature. The lung was a dull brick colour and haematite dust flowed out with the fluid when the lung was sectioned. The right lung presented a similar appearance to the left. There was a solid dense fibrosis of the upper and middle lobes and the lower lobe showed fibrosis with hypertrophic emphysema. There was no evidence of tuberculosis and on palpation, a dense fibrosis was found with no nodular formation whatever. On section, it showed a similar appearance of a brick-dust colour, dilated bronchi and uniform fibrosis of the upper and middle lobes with no crepitant lung tissue. The pericardial sac was slightly increased in size due to a hypertrophied and dilated heart. The hypertrophy was mostly on the right side and there was a terminal dilatation of the right atrium; the valves and coronary vessels unremarkable.The liver was small and on section showed venous congestion and cloudy swelling. Microscopy: On microscopy, sections of lung show a diffuse fibrosis of both upper lobes with no recognizable lung tissue. The fibrosis in areas has a slightly whorled arrangement, the centre of which is hyaline and contains no iron pigment and surrounding it is a zone of cellular tissue containing masses of iron. In the upper part of the lower lobe where the lung tissue is recognizable as such, a few nodules definitely resembling silica nodules are to be seen. In the both lower lobes a solid oedema was noted and emphysema marked. The fibrosis was not present to anything like the same extent in the lower lobes, the emphysema being the most marked feature. No evidence of tuberculosis was found in either lung, though a calcareous gland was found in the hilum. Under polarised light, the iron showed up as a golden brown with a few points of light, clear, needle-like in contra-distinction to the iron lying free in the fibrous tissue. The macrophages are beautifully shown lying inside the alveoli filled with iron dust. Percentage of Ash 16.6 Percentage of silica to ash 6.6 Percentage of silica to dry lung 1.1 Percentage of iron to ash 10.3 Percentage of iron to dry lung 6.7 Comments: In summary, the post mortem findings were of: Dense pulmonary fibrosis; hypertrophied and dilated right ventricle; failure of compensation. This condition is described as haematite miner's lung or sidero-silicosis, caused by the inhalation of dust containing silica and ferric oxide which is the principal component of the ore. The fibrosis is thought to be caused primarily by the silica and the exact role of the iron pigment in the pathogenesis of the lesion is not clear. The earliest lesions occur as small densely fibrous, sub-pleural foci usually in the upper lobes; these grow by coalescence of adjacent foci until a diffuse fibrosis of the whole lobe is produced. Haematite miner's fibrosis is commonly associated with tuberculosis and other chronic lung infections; in addition there is quite a high incidence of carcinoma of the lung reported in these cases. -

Chip of wood from an almond tree

Said to be a chip from the tree under which David Livingstone is said to have proposed to Mary Moffat 1884. Wood chip was donated by R.F. Immelman who purchased it from Kimberley museum. -

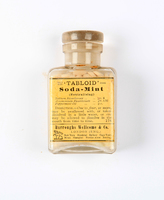

Soda-Mint (Neutralising)

"Antacid, exhilarant and stimulant. From one to three as a neutralising agent, in irritable and acid conditions of the stomach, dyspepsia, flatulence, etc. They may be swallowed with water, or be powdered and dissolved in water and taken as a draught" (BWC 1925:138). -

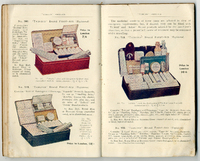

'Tabloid' A Brief Medical Guide (Back cover)

A guide to illnesses common to tropical regions and how to cure them using Burroughs Wellcome & Co.'s products -

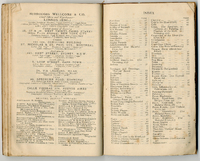

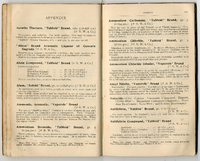

'Tabloid' A Brief Medical Guide (End pages)

A guide to illnesses common to tropical regions and how to cure them using Burroughs Wellcome & Co.'s products -

'Tabloid' A Brief Medical Guide (p148)

A guide to illnesses common to tropical regions and how to cure them using Burroughs Wellcome & Co.'s products -

'Tabloid' A Brief Medical Guide (p146,147)

A guide to illnesses common to tropical regions and how to cure them using Burroughs Wellcome & Co.'s products -

'Tabloid' A Brief Medical Guide (p144,145)

A guide to illnesses common to tropical regions and how to cure them using Burroughs Wellcome & Co.'s products -

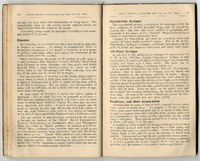

'Tabloid' A Brief Medical Guide (p142,143)

A guide to illnesses common to tropical regions and how to cure them using Burroughs Wellcome & Co.'s products -

'Tabloid' A Brief Medical Guide (p140,141)

A guide to illnesses common to tropical regions and how to cure them using Burroughs Wellcome & Co.'s products -

'Tabloid' A Brief Medical Guide (p138,139)

A guide to illnesses common to tropical regions and how to cure them using Burroughs Wellcome & Co.'s products -

'Tabloid' A Brief Medical Guide (p136,137)

A guide to illnesses common to tropical regions and how to cure them using Burroughs Wellcome & Co.'s products -

'Tabloid' A Brief Medical Guide (p134,135)

A guide to illnesses common to tropical regions and how to cure them using Burroughs Wellcome & Co.'s products -

'Tabloid' A Brief Medical Guide (p132,133)

A guide to illnesses common to tropical regions and how to cure them using Burroughs Wellcome & Co.'s products -

'Tabloid' A Brief Medical Guide (p130,131)

A guide to illnesses common to tropical regions and how to cure them using Burroughs Wellcome & Co.'s products -

'Tabloid' A Brief Medical Guide (p128,129)

A guide to illnesses common to tropical regions and how to cure them using Burroughs Wellcome & Co.'s products -

'Tabloid' A Brief Medical Guide (p126,127)

A guide to illnesses common to tropical regions and how to cure them using Burroughs Wellcome & Co.'s products -

'Tabloid' A Brief Medical Guide (p124,125)

A guide to illnesses common to tropical regions and how to cure them using Burroughs Wellcome & Co.'s products -

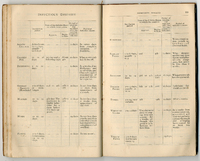

'Tabloid' A Brief Medical Guide (p122,123)

A guide to illnesses common to tropical regions and how to cure them using Burroughs Wellcome & Co.'s products -

'Tabloid' A Brief Medical Guide (p120,121)

A guide to illnesses common to tropical regions and how to cure them using Burroughs Wellcome & Co.'s products -

'Tabloid' A Brief Medical Guide (p118,119)

A guide to illnesses common to tropical regions and how to cure them using Burroughs Wellcome & Co.'s products -

'Tabloid' A Brief Medical Guide (p116,117)

A guide to illnesses common to tropical regions and how to cure them using Burroughs Wellcome & Co.'s products -

'Tabloid' A Brief Medical Guide (p114,115)

A guide to illnesses common to tropical regions and how to cure them using Burroughs Wellcome & Co.'s products -

'Tabloid' A Brief Medical Guide (p112,113)

A guide to illnesses common to tropical regions and how to cure them using Burroughs Wellcome & Co.'s products -

'Tabloid' A Brief Medical Guide (p110,111)

A guide to illnesses common to tropical regions and how to cure them using Burroughs Wellcome & Co.'s products -

'Tabloid' A Brief Medical Guide (p108,109)

A guide to illnesses common to tropical regions and how to cure them using Burroughs Wellcome & Co.'s products -

'Tabloid' A Brief Medical Guide (p106,107)

A guide to illnesses common to tropical regions and how to cure them using Burroughs Wellcome & Co.'s products -

'Tabloid' A Brief Medical Guide (p104,105)

A guide to illnesses common to tropical regions and how to cure them using Burroughs Wellcome & Co.'s products -

'Tabloid' A Brief Medical Guide (p102,103)

A guide to illnesses common to tropical regions and how to cure them using Burroughs Wellcome & Co.'s products -

'Tabloid' A Brief Medical Guide (p100,101)

A guide to illnesses common to tropical regions and how to cure them using Burroughs Wellcome & Co.'s products -

'Tabloid' A Brief Medical Guide (p98,99)

A guide to illnesses common to tropical regions and how to cure them using Burroughs Wellcome & Co.'s products -

'Tabloid' A Brief Medical Guide (p96,97)

A guide to illnesses common to tropical regions and how to cure them using Burroughs Wellcome & Co.'s products -

'Tabloid' A Brief Medical Guide (p94,95)

A guide to illnesses common to tropical regions and how to cure them using Burroughs Wellcome & Co.'s products -

'Tabloid' A Brief Medical Guide (p92,93)

A guide to illnesses common to tropical regions and how to cure them using Burroughs Wellcome & Co.'s products -

'Tabloid' A Brief Medical Guide (p90,91)

A guide to illnesses common to tropical regions and how to cure them using Burroughs Wellcome & Co.'s products -

'Tabloid' A Brief Medical Guide (p88,89)

A guide to illnesses common to tropical regions and how to cure them using Burroughs Wellcome & Co.'s products -

'Tabloid' A Brief Medical Guide (p86,87)

A guide to illnesses common to tropical regions and how to cure them using Burroughs Wellcome & Co.'s products -

'Tabloid' A Brief Medical Guide (p84,85)

A guide to illnesses common to tropical regions and how to cure them using Burroughs Wellcome & Co.'s products