Items

keywords is exactly

medicine chest

-

Chest: a botanical ecology

Illness and disease affect us all. The treatment of these conditions however, has been vast and varied, depending on the historical periods and the cultural context in and during which they are practiced. Situated in the rock art gallery, where healing power is expressed in San paintings, this mobile set of cabinets explores a rich complex of healing practices through the display of a medicine chest which was donated to the university of Cape Town in 1978. This chest belonged to a British dentist, who practiced in Cape Town from 1904, and who bought the chest for a hunting trip he undertook in 1913 to (then) Northern Rhodesia. The idea of the chest then gives rise to a variety of forms of healing: from instruments used to exorcise evil spirits and children's letters written to celebrate a heart transplant; to medicinal flowers bought at the Adderley Street flower market. The exhibition aims to visualise and materialise illness and its treatment from historical, cultural and disciplinary perspectives. Drawing on well-established historical and contemporary connections between the disciplines of Botany, Medicine and Pharmacology, the exhibits also suggest latent links which are at times political, at times whimsical. -

First Aid: Homage to Joseph Beuys

This work by the artist, Susan Hiller, consists of 13 vintage felt-lined wooden first aid boxes, 86 vintage bottles, water from holy wells and sacred streams, and vintage medical supplies. -

Taxonomy

Visually categorising a selection of my research material (accumulated since 2015). -

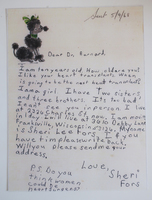

'Do you think women could be heartsurgens?'

Dear Dr Barnard, I am ten years old. How old are you? I like your heart transplants. When is going to be the next heart transplant? I am a girl. I have two sisters and three brothers. Its too bad I can't see you in person. I live at 2326 Charles St. now. I am moving in 1 day. I will live at 3610 Denny Lane, Franksville, Wisconsin. My name is Sheri Lee Fors. If you have time please write back. Will you please send me your address. Love, Sheri Fors. P.S. Do you think women could be heartsurgens? -

Playtone

Resulting from a 5-day taxonomy workshop which ran from 14 – 18 July 2014 as part of the Honours in Curatorship programme, the PLAYTONE exhibition depicts one of the various exercises students were asked to perform. Colours were allocated to groups, and students instructed to photograph all colour-coded objects during their daily routines, which were then classified using the PANTONE system. In addition to this, students also generated a selection of words they associated with their allocated colours and accumulated colour-coded personal belongings. Participants: Matthew Bradley, Annchen Bronkowski, Thea Ferreira, Sakhisizwe Gcina, Gail Gunston, Sharne McDonald, Mari McFarlane, Mosa Motaung, Thandiwe Msebenzi , Chloe Obermeyer, Bianca Packham, Lindelwa Pepu, Tazz Rossouw, Phenduliwe Sibisi -

Nina Liebenberg

The researcher who conducted this study and wrote the dissertation, 'The Virus and the Vaccine: Curatorship and the Disciplinary Outsider '(2021). -

A translated rock

In 2012, while exploring possible curatorial opportunities for the Honours in Curatorship students, I met with Sven Ouzman, a curator in the archeology department at Iziko, to chat about possible opportunities pertaining to this collection. I took him the newly designed course prospectus, to peruse. He flipped through it and when he got to the second last page, he paused. ‘Do you know the story behind this image’, he asked. I told him I didn’t… He pointed at the rock in the bottom right hand corner and started his story. Apparently this rock was not part of the SAN Rock art collection at all. It belonged to an archeologist who worked at the museum for close to twenty years. When she first started at the museum, her partner, now husband (and also an archeologist) also worked there with her. They were still in the beginning of their relationship and he was, to use older terminology, still courting her. One of the gifts he gave her during this period, was a rock he drew that mimicked San rock paintings, probably ones that would pertain to love in some way or other. She kept this in her office and, when she finally left the museum and had to empty her belongings, forgot to pack the rock as well. Exit archeologist, enter the lady who tidied the office before the new occupant moved in. On finding the rock she assumed it was part of the collection and returned it to the store room where it was assimilated into the bona fide rock art collection. I don’t know in how many exhibitions it subsequently appeared, but in 2010 it appeared up in Pippa Skotnes’s exhibition 'Made in translation' – an exhibition that fittingly explored ways in which translations from the landscape have been made and in so doing, placed images of rock art in the context of other forms of translation. -

Foxgloves

Called variously foxgloves, witch’s gloves, dead men’s bells, fairy’s gloves, bloody fingers, gloves of our lady, fairy caps, virgin’s gloves or fairy thimbles, Digitalis purpurea is popular with children, who pluck the tempting bell-shaped blooms and wear them like thimbles, admonished not to lick their fingers afterwards for fear they will go blind (Young 2002: 57). While the flower can be lethal if ingested, the drug digitalis derived from foxglove is most commonly used as a heart stimulant. Digitalis has been prescribed since the 17th century, perhaps earlier, as a diuretic and to slow the pulse and is still the drug of choice for atrial fibrillation. In the 1770s, William Withering got an old family recipe, a herbal infusion for treating swollen legs, from a Shropshire woman and identified digitalis as the active one of the twenty ingredients. Many more antiarrhythmic drugs now exist (Young 2002: 57). Made up of surgical gloves, Band-Aids, syringes and IV-tubing (with an infusion of foxglove leaves in its stem) the work mimicked the language of the herbarium specimen, drawing a viewer in to examine the content they were expecting, only to surprise them with its incongruous materials. -

Eucalyptus

"The plants [dislayed in this cabinet] were bought from the Adderley Street flower market in central Cape Town and are used by the sellers for medicinal purposes to treat chest and respiratory problems, with the leaves of the eucalyptus added to a bath and those of the protea infused in hot water and drunk as a broth. The flower sellers trading in Trafalgar Place and along Adderley Street have been doing so since at least the mid-1880s but became viewed as threats to the local flora by the European settlers at about the same time the medicine chest was first introduced to the city at the beginning of the 20th century. The settlers initially preferred to cultivate plants imported from their home countries to indigenous varieties, introducing many species to South Africa for nostalgic or practical reasons (subsequently problematic for local biodiversity) (Van Sittert 2002: 103). In the wake of emerging white nationalism in the 1890s, interest in indigenous plants gained momentum and was deployed to create a sense of belonging to the ‘foreign’ land (Boehi 2013: 133). A botanical discourse was mobilised to underscore ideas about identity and belonging, such as ‘roots’ and ‘ideas of rootedness’, and laws regulating flower picking (which usually occurred on the mountain) were passed in this period and were secured by the Wild Flower Protections Act in 1905 and an amendment thereto in 1908 (Boehi 2013: 133)"(Liebenberg 2021: 275). -

Proteas

"The plants [dislayed in this cabinet] were bought from the Adderley Street flower market in central Cape Town and are used by the sellers for medicinal purposes to treat chest and respiratory problems, with the leaves of the eucalyptus added to a bath and those of the protea infused in hot water and drunk as a broth. The flower sellers trading in Trafalgar Place and along Adderley Street have been doing so since at least the mid-1880s but became viewed as threats to the local flora by the European settlers at about the same time the medicine chest was first introduced to the city at the beginning of the 20th century. The settlers initially preferred to cultivate plants imported from their home countries to indigenous varieties, introducing many species to South Africa for nostalgic or practical reasons (subsequently problematic for local biodiversity) (Van Sittert 2002: 103). In the wake of emerging white nationalism in the 1890s, interest in indigenous plants gained momentum and was deployed to create a sense of belonging to the ‘foreign’ land (Boehi 2013: 133). A botanical discourse was mobilised to underscore ideas about identity and belonging, such as ‘roots’ and ‘ideas of rootedness’, and laws regulating flower picking (which usually occurred on the mountain) were passed in this period and were secured by the Wild Flower Protections Act in 1905 and an amendment thereto in 1908 (Boehi 2013: 133)" (Liebenberg 2021: 275). -

Livingstone

A small wooden chip from the same object collection as the medicine chest balanced on top of one of the bottles from the chest. "The treatment, the Livingstone rouser, was formulated by Dr Livingstone, who, after an attack of malaria in 1853, patented this mixture of quinine and purgatives (calomel, rhubarb and jalop) mixed with opium (Barrett & Giordani 2017: 1655–1666). The chip balanced on its lid is said to be from the almond tree under which he proposed to Mary Moffat in 1844. The juxtaposition of these two objects, one representing the quantifiable and the other the poetic, draws the viewer to consider the conflation of these two realms" (Liebenberg 2021: 273). -

Healing instruments

“I invited Edmund February to the Kirby collection to view the instruments and learn his thoughts on them from a botanical perspective. February identified the dancing rattles as being made of the seed pods of Oncoba spinosa (Venda: mutuzwa) and the seed pod of Adansonia digitata (Venda: muvhuyu). The wood of the iodophone was, however, unrecognisable as a result of its handling. February also contacted colleagues in the Department of Zoology and the School of Mathematical & Natural Sciences at the University of Venda, who connected me to a Venda diviner, Muanalo Dyer, who uses similar baobab rattles (and other materials from that tree) in her healing practices. This interdisciplinary engagement showed that these instruments, supposedly frozen in their early 20th century understanding of being on the brink of extinction, remained very much functional in the present” (Liebenberg 2021: 271). -

Listen Laennec

"In this work, the temperature graphs of individuals suffering from malaria, yellow fever, trypanosomiasis and tickborne-relapse fever – all viewed as ‘tropical’ and treatable by the contents of the medicine chest – were converted into a musical score. I punched the strips of paper of a hand-cranked musical box mechanism with holes that corresponded to the graphs – the vertical axis representing temperature variations and the horizontal axis representing the approximate number of days the fever is said to last. The translation of these graphs into notes seems nonsensical, as we do not listen for a temperature; we measure it by feeling a forehead or taking a reading with a thermometer. The practice of listening has, however, been part of the history of medicine since the days of Hippocrates (c.460–c.370 BC), when physicians performed auscultations of the lung and heart by placing their ear directly on the patient’s chest' (Liebenberg 2021: 265). -

Broken

"This cabinet displayed a round-bottomed flask that broke during the installation of the exhibition, and which I attempted to mend. The accompanying BWC medicine chest manual highlights the qualities the company wanted to portray as unique to the Tabloid medicine chest and that they believed would set them apart from competitors – such as the longevity of the medicines they sold and the indestructability of the chests (BWC 1925: 2–3). Addressing the supposed indestructability of the chest by focusing specifically on the wide array of glass-stoppered bottles that form a large part of its overall contents and which, according to BWC, ensured the longevity of the medicines, this exhibit displayed a laboratory bottle of similar material, but in a state that demonstrates its fragility. As such, it subverts BWC’s grand claims of indestructability and thereby throws the rest of its claims into doubt" (Liebenberg 2021: 259). -

Forest

"The bottles and pipettes in 'Forest' were originally sourced from the storage rooms of the Chemistry department, where they awaited disposal. This cabinet responded to the lacuna of indigenous material represented by the chest and addressed this imbalance by filling the bottles with teas made from local medicinal plants. Staging the bottles and pipettes to simulate a forest references the prejudice of Burroughs, Wellcome and Co (BWC) against these natural remedies, ‘purifying’ them through laboratory processes before they were deemed trustworthy and marketable. This process also occluded the original source of the remedies and sowed the seeds of biopiracy. The various items of glassware in this cabinet were filled with a selection of infusions made from Balotta africana, Sutherlandia frutescens, Agathosma crenulata, Melianthus major, Mentha longifolia, Petroselinum crispum, Hypoxiz villosa and Salvia officinalis" (Liebenberg 2021: 255). -

The Mother of all Firewalls

'The Mother of all Firewalls' (2012), is a sculptural piece by Kim Gurney made from beeswax, gold glitter, bitumen, repurposed tiles, rabbit skin and glue, which seems to depict an EEG graph in its format but in reality references a graph plotted by Google Insights after Gurney inputted a range of new words that emerged from the ‘Eurogeddon’ of 2012, showing their incidence in news reports pertaining to this financial crisis between 2008 and 2012. -

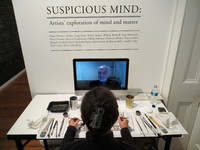

Suspicious Mind (Performance)

UCT’s Professor Mark Solms, then chairperson of the NPSA and one of the main organisers of the annual international Neuropsychoanalysis conference (2013), highlights Katherine Bull’s contribution to the 'Suspicious Mind' exhibition as one that stood out for him. His interpretation of the ambidextrous portraits she painted of him reveals an insider’s insight of an outsider object and shows how Bull’s artistic process enables theories postulated in his field to manifest in unusual ways: "She painted my double portrait – with her left and right hand simultaneously – over Skype, and she did the same of my beloved (now deceased) colleague Jaak Panksepp on site at the exhibition. I am the grateful owner of both of those double portraits. They hang in my sitting room, so I am reminded daily of the conference and of my departed friend. It is fascinating to see how Bull’s two hemisphere’s processed both me and Jaak each in their different ways. In both of our cases, her left hemisphere painted us with heads that sloped slightly to the right and contained more precise detail; while her right hemisphere painted us more impressionistically, but I think captured our ‘souls’ more accurately" (Liebenberg 2021: 233 - 234) -

Where the Wild Things Are (Field study)

'Where the Wild Things Are' (21 October – 5 November 2014) explored the political, social and historical narratives embedded in the natural world through investigation, observation, mapping, archival research and art making. The exhibition consisted of various on-site interventions engaging with contemporary and historical spatial dynamics and the significance of Hiddingh Campus. The Egyptian Building (home to sculpture workshops and studios) was built on the site of a zoo established in the late eighteenth century that was replete with lion’s dens and a small lake that supposedly housed a hippo. The campus was also the home to UCT’s first Zoology and Botany building (now the Michaelis Building). This historical perspective highlights both the site’s colonial imprints and its early affiliation with the sciences. The UCT campus is divided into its main upper campus, a middle and lower campus, and a few satellite campuses, of which the Michaelis School of Fine Art and the South African College of Music form part. Students drew on the methodologies of artist/curator Mark Dion, collaborating with specialists from upper campus (entomologists, ornithologists and botanists) and Michaelis Fine Art students, to highlight its natural environment. The interventions occurred on different days, and over a two week period. A calendar was provided to stipulate event times and artwork appearances. Curated by Nina Liebenberg Participating artists: Christopher Swift, Dillon Marsh, Fritha Langerman, Thuli Gamedze, Pippa Skotnes, Alex Kaczmarek, Rone-Mari Botha, Jessica Holdengarde, Fanie Buys, Lara Reusch, Stephani Muller, Tegan Green, Evan Wigdorowitz, Mariam Moosa, C J Chandler, Adrienne Van Eeden-Wharton -

A 'Jungle'

"A ‘jungle’ consisted of a selection of pathological specimens from the Pathology Learning Centre that had been affected by typhoid fever, ascaris adult worms, yellow fever, amoebic ulcerations, tuberculosis and malaria. The diseases that afflicted these specimens were regarded as ‘tropical’. As described in Chapter One, BWC used the jungle as a significant terrain that called for a medicine chest to combat pathogens: ‘Whether you were valiantly saving your compatriot in war, traversing a dark African jungle, navigating one of the world’s first flying machines, exploring the most desolate place on earth, ascending the highest mountain in the world, or simply enjoying the windswept British coast, the chest would be there, ready for any ailment’ (Johnson 2008b: 255). BWC promoted their chests as the ideal antidote for a tropical landscape ‘at once full of potential wealth for imperial Britain, but simultaneously rife with disease’ (Johnson 2008b: 258) and claimed that the tropical colonies were ‘by far the most dangerous regions for travellers’ (BWC 1934: 8). It was here that ‘desolating ailments’ were encountered, all ‘particularly fatal to the so-called white man who originates in temperate climates’ (BWC 1934: 8). I adapted the colour of the images of afflicted intestines, livers, stomachs and brains and used them as material to construct a dense jungle that referenced this aspect of the medicine chest’s history. Printed on separate glass sections that fit into the cabinet at spaced intervals to create an illusion of depth and three-dimensionality, the work draws on the cross-sectional display technique used in many anatomy museums worldwide, in projects such as the Visible Human Project (1995) and that the artist Damien Hirst references in his works . Creating a visual link between the UCT specimens and the history of these diseases surfaces the occluded racial undertones of these understandings" (Liebenberg 2021: 267). -

Buttons

A display of a collection of pins, buckles and buttons excavated from the washing pools used by slaves on Table Mountain. Taken from their dusty boxes in storage they are currently exhibited as part of Skotnes's 'Division of the World' (Department of Archaeology). -

Isigubu through Gqom

"In 2018, the Zulu drum alleged to have been played during the 1906 Bambatha rebellion against British rule and unfair taxation in the colony of Natal (discussed by Nixon) became the focus of Amogelang Maledu’s Honours research project. In ‘Isigubu through gqom: The sound of defiance and Black joy’, Maledu (who has an undergraduate degree in Anthropology and Visual Culture) used the drum’s history of colonial resistance and contextualised it through the contemporary musical genre of gqom, showing music as both an act and celebration of joy and freedom and of defiance against the limitations of township life. Through her ‘speculative and imagined interconnectedness’ of the isigubu and gqom, Maledu appropriated the limited information available about the former and expanded it by reinventing new historical pathways that reframed colonial narrations and aesthetics (Maledu 2018: 29–30). Her curation broke the silence of the Kirby instruments and liberated the isigubu from its ethnomusicological framework through a juxtaposition that spoke back to history and the contemporary moment. In addition, a website provides a framework for historicising gqom and encouraged the growth of its archive through viewer engagement, also highlighting the speculative and stagnant colonial archive in which the isigubu is situated (Maledu 2018: 29–30)" (Liebenberg 2021: 211 - 212). -

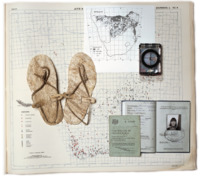

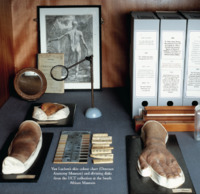

Page 175 of the Curiosity CLXXV catalogue

"The page presents a curated collection of images: a map from the Avian Demography Unit illustrating the distribution of the bataleur Terathopius ecaudatus along the political border, though the bateleur is more frequently found where there is no formal farming; a Ngwato child’s oxhide sandals collected by Isaac Schapera (a British social anthropologist who worked in South Africa and Botswana); a compass; the identification documents of Paula Ensor (previous dean and Professor of Education), who spent time in exile in Botswana; and a Certificate of Registration necessary for movement across borders, all of which are overlaid on top of a large map from the Afrikaans Atlas provided by Rajend Mesthrie of the Department of Linguistics and Southern African Languages that shows the Afrikaans language’s distribution. Contextualising all of these objects in relation to the large map cuts across disciplinary boundaries and illustrates the scope and impact of the colonial and apartheid regimes and their influence on immigration laws, language studies, ornithology and anthropology" (Liebenberg 2021: 193). -

Division of the World

"Undergraduate students regularly engage in discussions around certain displays as part of their teaching programme (N. Zachariou, personal communication, 27 May 2020), and the installation is also used to introduce visitors (exchange students and school children, for example) or students from other UCT departments (architecture students taking the archaeology module) to the department and the discipline (J. Parkington, personal communication, 20 June 2020). It has even been described as a ‘super curriculum’ (or as ‘several super curriculums’) for how it visualises what archaeology does on both an empirical and procedural level (J. Parkington, personal communication, 20 June 2020)" (Liebenberg 2021: 210). -

Subtle Thresholds (PLC)

"Integrated into the PLC, these works speak to the specimens on display and provide interesting access points to the collection. The animal-faeces prints (which referenced ‘sites of contamination’ in the context of the SAM exhibition) resonate, for instance, with many of the specimens on display in the PLC, such as the heterotopic heart (also called a ‘piggy-back heart transplant’) created by Dr Chris Barnard in 1977, consisting of a baboon heart grafted onto a human heart for additional motoric support. In addition to their more ‘famous’ specimens, the centre also has an extensive intestinal worm collection and many organs affected by zoonotic diseases, such as a liver ravaged by malaria. This was not a conscious decision on the part of the artist-curator and illustrates how curation can draw attention to aspects of a collection and liberate new associations when brought into conversation with it" (Liebenberg 2021: 201). -

Pages 38-39 of the Curiosity CLXXV catalogue

"Objects and collections can reflect naturalisations that occur when the disciplinary perspective renders its subject matter in terms of what it deems worth looking at and how it should be looked at (Daston & Galison 2007: 23). This process has dual consequences, resulting in the honing of a specialised insider focus directed at the object and a blindness to qualities that sit outside the disciplinary frame of reference (as discussed in relation to the Drennan and Kirby collections). 'Curiosity CLXXV' drew on and challenged both these aspects by forcing objects into visual conversations outside their discipline and inviting insiders to view them in these new configurations. These curatorial strategies enabled insiders to become aware of characteristics not normally deemed important in their discipline and to identify the characteristics their discipline did deem important (their attentional subculture, in other words) in objects not studied in their field" (Liebenberg 2021: 180). -

Face value

"In 1993, the [Lydenberg] heads were temporarily moved from the SAM stairs into the SANG as part of Payne’s exhibition. In the gallery context, where ‘the shifting definitions of art, the meaning of objects, the contexts of spaces as well as the politics of culture are continuously examined’ (Martin in Payne 1993: 4), these objects became part of an exhibition of Payne’s own terracotta heads, painted and sculpted cases, etchings inspired by the heads, drawings and a collection of supermarket trolleys" (Liebenberg 2021: 159 - 160). -

Etching from 'Sound from the Thinking Strings'

"Skotnes’s own visual interpretation of the history and cosmology of the |xam formed the last component of this interdisciplinary endeavour and constituted a visual component that drew together the various strands of disciplinary interpretations and presented a perspective on the |xam life she felt ‘was missing from the other interpretations’ (Skotnes 1991: 30). In these images she drew freely on San mythology, accounts of |xam life recorded by Lucy Lloyd, historical and archaeological research and images from rock paintings in a landscape setting. She writes in her preface that these etchings were direct attempts at ‘inverting the museum dioramas’ in the ethnographic halls close to the exhibition and which, through their display of the San’s body casts, rendered them closer to specimens of biology than as members of a highly developed culture (Skotnes 1991: 52). By creating images that combined shamanistic rituals, entoptic spirals, plants, hunting bags, bows and arrows, snakes, eland-shaped rainclouds, colonists, musical instruments, shelters and therianthropic shapes, Skotnes eclipsed the static narratives of the dioramas and the object labels in the exhibition, placing them in a context in which their metaphysical qualities were celebrated more than their physical qualities. These prints stood in striking contrast to the other exhibits, which framed the San as physical types, and they challenged viewers to confront the reality that the San had a rich history and cultural and social life" (Liebenberg 2021: 157). -

Sound from the Thinking Strings (installation detail)

"Skotnes had a longstanding relationship with the museum, which started when she was still a student at the Michaelis School of Fine Art. Davison remembers that Skotnes would visit the taxidermy section of the South African museum to draw bones. As an anthropologist, Davison admits to finding Skotnes’s way of looking at things stimulating – an individual way of looking at objects that made her look at them differently, even though she was already very familiar with these materials. Davison recalls a visit to the ethnographic stores during which she showed Skotnes the San skin bags, carefully conserved in their drawers and laid out on acid-free paper. Skotnes admired not only their aesthetic qualities but related the stories she had been studying in the Bleek and Lloyd archive to them – stories that shifted their status from anthropological museum objects to powerful animate objects in San spiritual and social life (P. Davison, personal communication, 28 January 2021). Skotnes remembers that she asked staff whether they knew what was inside the bags and was shocked when nobody could remember looking in them. She was allowed to look inside one and found a claw, which they thought must be a leopard’s (P. Skotnes, personal communication, 9 May 2021)" (Liebenberg 2021: 2015). -

Miscast (installation detail)

Instruments from the Kirby collection displayed as part of the 'Miscast' exhibition. -

Page 135 of the Curiosity CLXXV catalogue

"Peering into one of them could, for instance, reveal musical instruments from the South African College of Music’s Kirby collection; old wooden mathematical models of abaci and polyhedrons from the Maths department; mobiles demonstrating platonic solids made by mechanical engineering students; publications by a UCT Professor of Astronomy; a sign pointing to ward D10 from the old section of Groote Schuur Hospital; glass slides once used as a teaching aid for art history at Michaelis; bird ringing material from the Avian Demography unit; and a bottle-brush plant labelled by the son of one of the curators" (Liebenberg 2021: 179). -

The Kirby collection of musical instruments

"Kirby’s choice of an ‘age-old simple classification’ to order the instruments can be correlated with another classification formulated at Wits around the time he was collecting. The Department of Bantu Studies was established in the 1920s at roughly the same time as the Music Department. Kirby’s use of the phrase ‘native races’, which features in the title of his book, resonates with the descriptive subtitle of the Wits journal connected to research in this department: Bantu Studies: A Journal Devoted to the Scientific Study of Bantu, Hottentot, and Bushman (Nixon 2013: xii). The homogenising act of categorising all diverse indigenous South African groups into three general categories seems to echo Kirby’s taxonomic imposition on the diverse instruments he collected on his trips and that continues to feature as the ordering principle of this collection" (Liebenberg 2021: 136). -

The workshop

"Held in the Department of Human Biology in the Division of Clinical Anatomy and Biological Anthropology, this collection consists of prepared specimens – both bottled and plastinated, anatomical models – and a skeletal repository used for research purposes. The materials are kept in three separate rooms, with the anatomical models in one, the prepared and plastinated specimens in another and the skeleton repository in its own room behind locked doors, viewable by appointment only. The room housing the anatomical models functioned as a workshop when modelmaking was still offered to first year medical students as an elective course: its walls are lined with shelves that display models made from materials ranging from papier-mâché to modern silicon copies and are taxonomised according to their anatomical representations, such as ‘the eye’, ‘head & neck’, ‘dentistry’, ‘embryology’, ‘lungs’ and ‘cardiovascular system’, to name a few. The models represent each anatomical section and are brightly coloured to differentiate the different parts of the human body and aid in identification. Many of the models can be dismantled into separate pieces and, like a puzzle, be reassembled into their original shapes. Interspersed with these models are rolled-up charts depicting organs, bodily systems and anatomical sections of the body in two-dimensional form, as well as old student modelling projects. A selection of animal skeletons is displayed on the far side of the room, and a shelf with a few anatomical specimens in formaldehyde is across from it" (Liebenberg 2021: 121 - 122). -

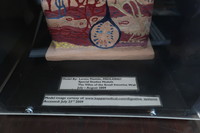

'Villus of the small intestine wall'

A student model of the ‘Villus of the small intestine wall’ found in the workshop of the Anatomy Building, UCT. -

Miscast (Lane reflects)

"Where viewers had to walk over a floor of vinyl tiles printed with photocopied newspaper articles and photographs of the San, Lane reflected on another archaeological parallel: ‘just as the texts and images on the floor represent the debris of a particular history, so too do the artefacts strewn across the surface of a site’ (Lane 1996: 7). Yet in trying to define sites and their history, archaeologists feel ‘they can tread on the debris of their own or others’ ancestors with equanimity, colonizing that space for themselves’ (Lane 1996: 7)" (Liebenberg 2021: 172 - 174). -

Miscast (installation detail)

"In juxtaposing instruments that are still being used (such as the scalpel and the camera) with ones that are not (the Von Luschan skin colour chart and the anthropometric measuring rods), Skotnes set up an opportunity for science to reflect on its past and on the activities and objects of its present, enabling a mode of self-reflexivity that is not a standard part of its day-to-day practices. Through curatorship, she exposed disciplinary practitioners to naturalisations and blind spots within their fields and sensitised them to these previously occluded characteristics" (Liebenberg 2021: 172). -

Page 65 of the Curiosity CLXXV catalogue

Page 65 of the 'Curiosity CLXXV' catalogue, showing the Old Anatomy Lecture Theatre (currently part of the Centre for Curating the Archive). -

Page 79 of the Curiosity CLXXV catalogue.

"Created by Felix von Luschan, an Austrian doctor, anthropologist, explorer, archaeologist and ethnographer in the early 20th century, the chart, known as the Von Luschan chromatic scale (...) was used to classify skin colour and featured as a tool in race studies and anthropometry of the time. Forgotten by its current department staff and students, its presence draws attention to the role of medicine and science in the apartheid agenda and to the larger racist scientific practices of measuring and classifying human physical differences in the 19th and 20th centuries to produce a ‘typology of race’ (Sturken & Cartwright 2018: 351–352). To support such theories, object collections in scientific university departments worldwide also featured collections of human remains; tools for measuring the size and shape of skulls; and charts detailing various physiognomic features (Sturken & Cartwright 2018: 351 – 352)" (Liebenberg 2021: 122 - 125). -

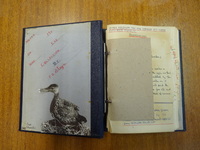

Diary of an oologist

"In 2019, Honours in Curatorship student Nathalie Viruly, who completed her Bachelor of Social Science in Politics and Sociology, was similarly struck by the silence and loss evoked by the [Peter Steyn] collection. Viruly honed in on the moments documented in the notebooks, which capture the loss of life in the reproductive life of these birds and reveal ‘stories of avian tragedy’: Young taken by predator; 1 young accidentally killed; 2 eggs failed to hatch; 2 infertile; Chick disappeared without a trace; Eggs disappeared; Literally cooked by the [corrugated] roof; Nest empty – egg collectors? (Viruly 2018: online). Her focus on these moments in the scientific journal poignantly reveals the conflation between science and emotion and invites the viewer to re-examine hierarchies of loss" (Liebenberg 2021: 219). -

Stone tools

"By positioning artefacts to emphasise their labelling (stones are positioned to reveal the details written on them), including seemingly familiar objects and expanding and shrinking timelines, the installation [Division of the World] draws attention to the framing devices, tools and methods of the department’s insiders" (Liebenberg 2021: 207). -

Things zoological insiders look at

A sample box of archaeological specimens shown to first year students. -

Things archaeological insiders look at

A variety of pottery shards of Asian porcelain, European earthenware and British stoneware in a drawer in the Department of Archaeology, UCT. -

Weighing Smoke

PAUL That’s the man. Well, Raleigh was the person who introduced tobacco in England, and since he was a favourite of the Queen’s – Queen Bess, he used to call her – smoking caught on as a fashion at court. I’m sure Old Bess must have shared a stogie or two with Sir Walter. Once, he made a bet with her that he could measure the weight of smoke. DENNIS You mean, weigh smoke? PAUL Exactly. Weigh smoke. TOMMY You can’t do that. It’s like weighing air. PAUL I admit it’s strange. Almost like weighing someone’s soul. But Sir Walter was a clever guy. First, he took an unsmoked cigar and put it on a balance and weighed it. Then he lit up and smoked the cigar, carefully tapping the ashes into the balance pan. When he was finished, he put the butt into the pan along with the ashes and weighed what was there. Then he subtracted that number from the original weight of the unsmoked cigar. The difference was the weight of the smoke. TOMMY Not bad. That’s the kind of guy we need to take over the Mets. PAUL Oh, he was smart, all right. But not so smart that he didn’t wind up having his head chopped off twenty years later. (Pause) But that’s another story. -

Dialogue goggles

-

The experiment (Wine into water)

An experiment in three parts, reversing the first miracle. -

Film still from Paolo Pasolini’s 'Salò'

A film still from Paolo Pasolini’s 'Salò, or the 120 days of Sodom' (1975), in which a protagonist turns his binoculars around to create distance between himself and the scene of torture playing out in the courtyard below. -

Weighing Air

An example from demonline (UCT Physics Department’s website with descriptions of educational demonstrations). Its descriptions reads: "A spherical flask of about 1 litre is suspended from one arm of a crude chemical balance. It is counterpoised by weights in the other pan, the tap attached to the sphere being open. This gives (roughly) the true weight of the glass. Unhook the sphere from the stirrup, attach the rubber tube from a rotary vacuum pump to the glass tube and evacuate for around 30s. Close tap, and re-attach stirrup. There will now be an upthrust on the flask equal to the weight of air removed, and the weights in the other pan will have to be reduced by about 1.2 g to restore the balance. Open the tap again: the air can be heard rushing into the flask (class must keep quiet), and the flask suddenly descends again". -

Appendix (installation shot)

A variety of pottery shards consisting of Asian porcelain, European earthenware and British stoneware sourced from the University of Cape Town Archaeology department and subjected to a botanical analysis by a graduate of the Biological Science (Botany) Department. -

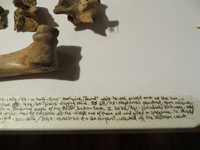

Appendix (installation shot)

A variety of bones sourced from the University of Cape Town Archaeology and Zoology departments, playfully re-imagined by the students as a collection owned by a time-travelling anthropologist - collecting samples across time and sometimes, across dimensions. -

Planthology (detail)

“For 'Planthology (Bulbine frutescens and Lessertia frutescens)' I sourced two medicinal plant specimens from Kirstenbosch National Botanical Garden and x-rayed them at Groote Schuur Hospital (#10 and #13). These two local plants offer a wide variety of healing properties and address the lacuna of the chest. The fresh leaves of the Bulbine frutescens produce a jelly-like juice that can be used for burns, rashes, blisters, insect bites, cracked lips, acne, cold sores, mouth ulcers and areas of cracked skin, while an infusion of these leaves in a cup of boiling water can be taken for coughs, colds and arthritis (Harris 2003: online). The Lessertia frutescens is used as an immune booster in the treatment of HIV/AIDS, as a medicine in the treatment of chicken pox, internal cancers, colds, asthma, TB, bronchitis, rheumatism, rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis, liver problems, haemorrhoids, piles, bladder and uterus problems, diarrhoea, dysentery, stomach ailments, heartburn, peptic ulcers, backache, diabetes, varicose veins and inflammation (Xaba & Notten 2003: online)” (Liebenberg 2021: 269). -

Planthology

In conversation with Dr Yeats in 2011 about adding a few medicinal plants to the centre as part of its displays, she mentioned that no plants survived in there. They all seemed to die from some mysterious cause. I decided to source three medicinal plants, the Lessertia frutescens, Bulbine frutescens and Artemisia afra, and X-ray them to 'diagnose' what might be the cause of their demise. In subjecting the plants to this process and placing the x-ray images in a space that foregrounds the diagnosis of human disease, I intended to create a heterarchical shift in this relationship, considering a world in which the degree of care directed toward human ailments might be replicated in treating diseases manifest in the botanical world.