Items

Site

The Medicine Chest

Is Part Of is exactly

African Studies

-

Eucalyptus

"The plants [dislayed in this cabinet] were bought from the Adderley Street flower market in central Cape Town and are used by the sellers for medicinal purposes to treat chest and respiratory problems, with the leaves of the eucalyptus added to a bath and those of the protea infused in hot water and drunk as a broth. The flower sellers trading in Trafalgar Place and along Adderley Street have been doing so since at least the mid-1880s but became viewed as threats to the local flora by the European settlers at about the same time the medicine chest was first introduced to the city at the beginning of the 20th century. The settlers initially preferred to cultivate plants imported from their home countries to indigenous varieties, introducing many species to South Africa for nostalgic or practical reasons (subsequently problematic for local biodiversity) (Van Sittert 2002: 103). In the wake of emerging white nationalism in the 1890s, interest in indigenous plants gained momentum and was deployed to create a sense of belonging to the ‘foreign’ land (Boehi 2013: 133). A botanical discourse was mobilised to underscore ideas about identity and belonging, such as ‘roots’ and ‘ideas of rootedness’, and laws regulating flower picking (which usually occurred on the mountain) were passed in this period and were secured by the Wild Flower Protections Act in 1905 and an amendment thereto in 1908 (Boehi 2013: 133)"(Liebenberg 2021: 275). -

Proteas

"The plants [dislayed in this cabinet] were bought from the Adderley Street flower market in central Cape Town and are used by the sellers for medicinal purposes to treat chest and respiratory problems, with the leaves of the eucalyptus added to a bath and those of the protea infused in hot water and drunk as a broth. The flower sellers trading in Trafalgar Place and along Adderley Street have been doing so since at least the mid-1880s but became viewed as threats to the local flora by the European settlers at about the same time the medicine chest was first introduced to the city at the beginning of the 20th century. The settlers initially preferred to cultivate plants imported from their home countries to indigenous varieties, introducing many species to South Africa for nostalgic or practical reasons (subsequently problematic for local biodiversity) (Van Sittert 2002: 103). In the wake of emerging white nationalism in the 1890s, interest in indigenous plants gained momentum and was deployed to create a sense of belonging to the ‘foreign’ land (Boehi 2013: 133). A botanical discourse was mobilised to underscore ideas about identity and belonging, such as ‘roots’ and ‘ideas of rootedness’, and laws regulating flower picking (which usually occurred on the mountain) were passed in this period and were secured by the Wild Flower Protections Act in 1905 and an amendment thereto in 1908 (Boehi 2013: 133)" (Liebenberg 2021: 275). -

Forest

"The bottles and pipettes in 'Forest' were originally sourced from the storage rooms of the Chemistry department, where they awaited disposal. This cabinet responded to the lacuna of indigenous material represented by the chest and addressed this imbalance by filling the bottles with teas made from local medicinal plants. Staging the bottles and pipettes to simulate a forest references the prejudice of Burroughs, Wellcome and Co (BWC) against these natural remedies, ‘purifying’ them through laboratory processes before they were deemed trustworthy and marketable. This process also occluded the original source of the remedies and sowed the seeds of biopiracy. The various items of glassware in this cabinet were filled with a selection of infusions made from Balotta africana, Sutherlandia frutescens, Agathosma crenulata, Melianthus major, Mentha longifolia, Petroselinum crispum, Hypoxiz villosa and Salvia officinalis" (Liebenberg 2021: 255). -

Isigubu through Gqom

"In 2018, the Zulu drum alleged to have been played during the 1906 Bambatha rebellion against British rule and unfair taxation in the colony of Natal (discussed by Nixon) became the focus of Amogelang Maledu’s Honours research project. In ‘Isigubu through gqom: The sound of defiance and Black joy’, Maledu (who has an undergraduate degree in Anthropology and Visual Culture) used the drum’s history of colonial resistance and contextualised it through the contemporary musical genre of gqom, showing music as both an act and celebration of joy and freedom and of defiance against the limitations of township life. Through her ‘speculative and imagined interconnectedness’ of the isigubu and gqom, Maledu appropriated the limited information available about the former and expanded it by reinventing new historical pathways that reframed colonial narrations and aesthetics (Maledu 2018: 29–30). Her curation broke the silence of the Kirby instruments and liberated the isigubu from its ethnomusicological framework through a juxtaposition that spoke back to history and the contemporary moment. In addition, a website provides a framework for historicising gqom and encouraged the growth of its archive through viewer engagement, also highlighting the speculative and stagnant colonial archive in which the isigubu is situated (Maledu 2018: 29–30)" (Liebenberg 2021: 211 - 212). -

Etching from 'Sound from the Thinking Strings'

"Skotnes’s own visual interpretation of the history and cosmology of the |xam formed the last component of this interdisciplinary endeavour and constituted a visual component that drew together the various strands of disciplinary interpretations and presented a perspective on the |xam life she felt ‘was missing from the other interpretations’ (Skotnes 1991: 30). In these images she drew freely on San mythology, accounts of |xam life recorded by Lucy Lloyd, historical and archaeological research and images from rock paintings in a landscape setting. She writes in her preface that these etchings were direct attempts at ‘inverting the museum dioramas’ in the ethnographic halls close to the exhibition and which, through their display of the San’s body casts, rendered them closer to specimens of biology than as members of a highly developed culture (Skotnes 1991: 52). By creating images that combined shamanistic rituals, entoptic spirals, plants, hunting bags, bows and arrows, snakes, eland-shaped rainclouds, colonists, musical instruments, shelters and therianthropic shapes, Skotnes eclipsed the static narratives of the dioramas and the object labels in the exhibition, placing them in a context in which their metaphysical qualities were celebrated more than their physical qualities. These prints stood in striking contrast to the other exhibits, which framed the San as physical types, and they challenged viewers to confront the reality that the San had a rich history and cultural and social life" (Liebenberg 2021: 157). -

Sound from the Thinking Strings (installation detail)

"Skotnes had a longstanding relationship with the museum, which started when she was still a student at the Michaelis School of Fine Art. Davison remembers that Skotnes would visit the taxidermy section of the South African museum to draw bones. As an anthropologist, Davison admits to finding Skotnes’s way of looking at things stimulating – an individual way of looking at objects that made her look at them differently, even though she was already very familiar with these materials. Davison recalls a visit to the ethnographic stores during which she showed Skotnes the San skin bags, carefully conserved in their drawers and laid out on acid-free paper. Skotnes admired not only their aesthetic qualities but related the stories she had been studying in the Bleek and Lloyd archive to them – stories that shifted their status from anthropological museum objects to powerful animate objects in San spiritual and social life (P. Davison, personal communication, 28 January 2021). Skotnes remembers that she asked staff whether they knew what was inside the bags and was shocked when nobody could remember looking in them. She was allowed to look inside one and found a claw, which they thought must be a leopard’s (P. Skotnes, personal communication, 9 May 2021)" (Liebenberg 2021: 2015). -

Miscast (installation detail)

Instruments from the Kirby collection displayed as part of the 'Miscast' exhibition. -

The Kirby collection of musical instruments

"Kirby’s choice of an ‘age-old simple classification’ to order the instruments can be correlated with another classification formulated at Wits around the time he was collecting. The Department of Bantu Studies was established in the 1920s at roughly the same time as the Music Department. Kirby’s use of the phrase ‘native races’, which features in the title of his book, resonates with the descriptive subtitle of the Wits journal connected to research in this department: Bantu Studies: A Journal Devoted to the Scientific Study of Bantu, Hottentot, and Bushman (Nixon 2013: xii). The homogenising act of categorising all diverse indigenous South African groups into three general categories seems to echo Kirby’s taxonomic imposition on the diverse instruments he collected on his trips and that continues to feature as the ordering principle of this collection" (Liebenberg 2021: 136). -

Miscast (Lane reflects)

"Where viewers had to walk over a floor of vinyl tiles printed with photocopied newspaper articles and photographs of the San, Lane reflected on another archaeological parallel: ‘just as the texts and images on the floor represent the debris of a particular history, so too do the artefacts strewn across the surface of a site’ (Lane 1996: 7). Yet in trying to define sites and their history, archaeologists feel ‘they can tread on the debris of their own or others’ ancestors with equanimity, colonizing that space for themselves’ (Lane 1996: 7)" (Liebenberg 2021: 172 - 174). -

Miscast (installation detail)

"In juxtaposing instruments that are still being used (such as the scalpel and the camera) with ones that are not (the Von Luschan skin colour chart and the anthropometric measuring rods), Skotnes set up an opportunity for science to reflect on its past and on the activities and objects of its present, enabling a mode of self-reflexivity that is not a standard part of its day-to-day practices. Through curatorship, she exposed disciplinary practitioners to naturalisations and blind spots within their fields and sensitised them to these previously occluded characteristics" (Liebenberg 2021: 172). -

Page 79 of the Curiosity CLXXV catalogue.

"Created by Felix von Luschan, an Austrian doctor, anthropologist, explorer, archaeologist and ethnographer in the early 20th century, the chart, known as the Von Luschan chromatic scale (...) was used to classify skin colour and featured as a tool in race studies and anthropometry of the time. Forgotten by its current department staff and students, its presence draws attention to the role of medicine and science in the apartheid agenda and to the larger racist scientific practices of measuring and classifying human physical differences in the 19th and 20th centuries to produce a ‘typology of race’ (Sturken & Cartwright 2018: 351–352). To support such theories, object collections in scientific university departments worldwide also featured collections of human remains; tools for measuring the size and shape of skulls; and charts detailing various physiognomic features (Sturken & Cartwright 2018: 351 – 352)" (Liebenberg 2021: 122 - 125). -

Planthology (detail)

“For 'Planthology (Bulbine frutescens and Lessertia frutescens)' I sourced two medicinal plant specimens from Kirstenbosch National Botanical Garden and x-rayed them at Groote Schuur Hospital (#10 and #13). These two local plants offer a wide variety of healing properties and address the lacuna of the chest. The fresh leaves of the Bulbine frutescens produce a jelly-like juice that can be used for burns, rashes, blisters, insect bites, cracked lips, acne, cold sores, mouth ulcers and areas of cracked skin, while an infusion of these leaves in a cup of boiling water can be taken for coughs, colds and arthritis (Harris 2003: online). The Lessertia frutescens is used as an immune booster in the treatment of HIV/AIDS, as a medicine in the treatment of chicken pox, internal cancers, colds, asthma, TB, bronchitis, rheumatism, rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis, liver problems, haemorrhoids, piles, bladder and uterus problems, diarrhoea, dysentery, stomach ailments, heartburn, peptic ulcers, backache, diabetes, varicose veins and inflammation (Xaba & Notten 2003: online)” (Liebenberg 2021: 269). -

Planthology

In conversation with Dr Yeats in 2011 about adding a few medicinal plants to the centre as part of its displays, she mentioned that no plants survived in there. They all seemed to die from some mysterious cause. I decided to source three medicinal plants, the Lessertia frutescens, Bulbine frutescens and Artemisia afra, and X-ray them to 'diagnose' what might be the cause of their demise. In subjecting the plants to this process and placing the x-ray images in a space that foregrounds the diagnosis of human disease, I intended to create a heterarchical shift in this relationship, considering a world in which the degree of care directed toward human ailments might be replicated in treating diseases manifest in the botanical world. -

‘Mrs Glover attending to an ill African chief.’

"The figure of ‘Mrs Glover’, kneeling and treating what appears to be a very ill man, exudes not only the authority of Western medicine within the local context but conveys her as the self-sacrificing and caring European ‘civilizer’ in service of expanding the empire, ‘the medicine chest conveniently by her side’ (Johnson 2008b: 259)" (Liebenberg 2021: 63 - 65). -

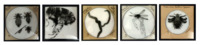

Hosts and Carriers

A selection of glass slides of the insects, ticks and worms that are the primary or intermediate hosts or carriers of human diseases. These slides also featured in the 'Curiosity CLXXV' and 'Subtle thresholds' exhibitions, sourced from the Pathology Learning Centre (PLC), where they were originally donated by the secretary of the Department of Microbiology. Dr Yeats identified them as glass photomicrographs and speculated that they were probably made for a special projector used for teaching many years ago. -

Clivia's in Kirstenbosch

Part of the ‘Useful plants’ section at Kirstenbosch National Botanical Garden. -

Rattles in the Kirby collection

A drawer of rattles in the South African College of Music's Kirby collection: "The instruments are now grouped in different cabinets according to the taxonomy set out by Kirby in his book. In the preface to the second edition (1964), Kirby shares some of his considerations when deciding how to group the instruments, writing that he had to decide ‘whether to arrange his material tribally, or to deal with each type of musical instrument separately from the technological and historical points of view, allowing the tribal aspects to emerge incidentally’ (Kirby 1964: xi). Kirby chose the second alternative, stating that his chief reason was that he wanted the work to be, as far as possible, ‘a complete and comparative study of one particular aspect of the life of our aborigines’ (1964: xi). His second consideration was to find the most suitable manner for classifying the instruments, for which he defaulted to the ‘age-old simple classification of musical instruments into three main groups of percussion, wind and strings’ (1964: xi) – a Western system for the classification of instruments and the principles on which they were based. The chapters in his book and the displays in the room are thus grouped into three categories: percussion – ‘rattles and clappers’, ‘drums’, ‘xylophones and sansas’ and ‘bull-roarers and spinning-disks’; wind instruments – ‘horns and trumpets’, ‘whistles, flutes, and vibrating reeds’ and ‘reed flute ensembles’; and stringed instruments – ‘stringed instruments’ and ‘Bushmen and Hottentot violins and the ramkie’. Kirby encountered one taxonomic anomaly when employing this system: the ‘gora’, an instrument both wind and string, which he termed ‘a stringed-wind instrument’" (Liebenberg 2021: 135). -

A1.44.

The contents of Floyd’s two travelling cases for his hunting trip (BC666 A1.44. Special Collections, University of Cape Town). -

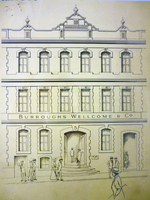

BWC Cape Town premises

"When Burroughs died of pneumonia in 1895, Wellcome became BWC’s sole owner, and the next 20 years (until the outbreak of World War I) constituted a period of massive expansion for the company (Bailey 2008: online). In 1898, the first overseas branch opened in Sydney and was followed by seven more branches – in New York, Montreal, Buenos Aires, Cape Town, Milan, Shanghai and Bombay – by 1912. The Cape Town branch opened in 1902, seven years after Wellcome made his first visit to the city in 1895" (Liebenberg 2021: 49 - 51). -

BWC Cape Town premises (drawing)

Line drawing of the Burroughs Wellcome & Co. office, Cape Town, South Africa. -

Corrections

Examples of Wellcome's design changes annotated on tracing paper. 1914–1938. WF/M/I/PR/O01/3, 4, 9, 8. Wellcome Collection. -

Miscast (instruments of measurement)

"Along with the guides that regulated practices and protocols to stabilise and standardise an individual’s response to unfamiliar and disorienting sights (Kennedy 2013: 42), the gender, class and ethnicity of the observer were also of importance , as was the use of ‘ever more sophisticated instruments and calculations designed to minimize the intrusion of subjectivity into the reporting of information’ (Driver 2001: 55). By regulating who was doing the viewing, stipulating what should be viewed and how and supplying tools to measure these observations, scientific institutions promoted an authoritative ‘way of seeing’ in the field that differentiated the scientific view from that of the ordinary traveller (Driver 2001: 49)" (Liebenberg 2021: 109). -

Sharpeville

The predominantly black community of Sharpeville was established near Vereeniging. On the 21st of March, 68 years after Vereeniging was first established, the Sharpeville massacre occurred. -

The conquest of time

An extract from an email from archaeologist and former head of African Studies, Prof Nick Shepherd (Jan 21, 2021, 11:33 AM): "Disciplinary practices and regimes of care constitute a kind of bureaucratization or governmentality of elapsed time and its material remains and human relationships, placing these remains and relationships under a kind of administration. We think of the elaborate structure of regional typologies and chronologies, the immense work of correctly assigning artefacts and sites to these imagined categories, and the vast institutional apparatus that supports these endeavors – all of which constitute archaeology as a formidable disciplinary enterprise. In the face of this enterprise, the “many worlds” of local claims to the past have little chance of success". -

Lacuna (Part one)

"It is interesting to note that the botanical origins of most of these medicines were from outside of Africa, especially if one considers the long history of the Cape as a point on the trade routes where ill sailors regularly disembarked and drew on the knowledge of the Khoekhoe traditional healers for treatment and herbal cures (Laidler & Gelfand 1971: 44). The Cape flora offered a plenitude of medicinal resources and these healers (who were skilled in botany, surgery and medicine) used them in a variety of healing practices . The exclusion of local botanical remedies in the BWC No. 254 medicine chest can be attributed to many factors" (Liebenberg 2021: 67). -

Iroko

Structurally, 'Chest: a botanical ecology' consisted of 15 modular interlocking cabinets of differing sizes which rested on top of one another, making up the front of the display. These were constructed from two types of wood, the darker iroko wood, and a lighter ash wood – with the iroko originating from the repurposed cabinets used for Curiosity CLXXV in 2004. The Iroko tree is a large hardwood tree from the west coast of tropical Africa, known by the Yoruba as ìrókò, logo or loko. Believed to have supernatural properties, it can live up to 500 years. Yoruba people believe that a spirit inhabits the tree, and anybody who sees the Iroko-man face to face becomes insane and dies. According to the Yoruba, any man who cuts down any Iroko tree causes devastating misfortune on himself and all of his family. In West Africa, the iroko wood is also used to make the djembe drum. If they however, need to cut down the tree, they can make a prayer afterwards to protect themselves. Used for a variety of purposes including boat-building, domestic flooring, furniture and outdoor gates, from the late 1990s, it was also used as part of the txalaparta, a Basque musical instrument constructed of wooden boards, due to its lively sound and classified as an idiophone (a percussion instrument) (Ogumfe 1929: online)). -

"Bought fresh in streets of Cape Town"

"The flower sellers trading in Trafalgar Place and along Adderley Street have been doing so since at least the mid-1880s but became viewed as threats to the local flora by the European settlers at about the same time the medicine chest was first introduced to the city at the beginning of the 20th century. The settlers initially preferred to cultivate plants imported from their home countries to indigenous varieties, introducing many species to South Africa for nostalgic or practical reasons (subsequently problematic for local biodiversity) (Van Sittert 2002: 103). In the wake of the emerging nationalism of the white settlers in the 1890s, interest in indigenous plants gained momentum and was deployed to create a sense of belonging to the ‘foreign’ land (Boehi 2013: 133). A botanical discourse was mobilised to underscore ideas about identity and belonging, such as ‘roots’ and ‘ideas of rootedness’, and laws regulating flower picking (which usually occurred on the mountain) were passed in this period and were secured by the Wild Flower Protections Act in 1905 and an amendment thereto in 1908 (Boehi 2013: 133)" (Liebenberg 2021: 275). This is a label on a botanical specimen (K000225239) found in the Royal Botanic Gardens of Kew that was donated to the Gardens by UCT. Described in pen in the notes section, the specimen is of the local Erica latiflora and was collected in 1908, when it was ‘bought fresh in the streets of Cape Town’. The insider details noted on this specimen reveal much to outsiders such as Boehi (2013) and Van Sittert (2010) – scholars who have written about the colonial history of botany in the Cape and the unofficial presence of the flower sellers in the provenance of many specimens from the Cape kept in international herbaria. -

"Bought fresh in streets of Cape Town"

Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew (K). Herbarium: Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew (K), K000225239. Collection: Herbarium Specimens. Resource Type: Specimens. Collector: unknown, #14027. Collection Date:11–1908. Locality: Bought fresh in streets of Cape Town. Country: South Africa (South Africa). Identifications: Type of Erica latiflora L.Bolus [family ERICACEAE] (stored under name). Notes: Herbarium Africanum Bolusianum Flora South Western Region -

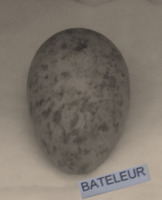

Bataleur egg

Situated in a locked bespoke cabinet in the Niven Library in UCT’s Percy Fitzgerald Institute of African Ornithology, this Bataleur eagle egg is part of a collection of eggs donated by the ornithologist Peter Steyn in 2007. Collected between 1961 and 1977, when Steyn spent time in Zimbabwe, the egg is a link to the iconic stone carved Zimbabwe Birds which once stood proudly on guard atop the walls and monoliths of the ancient city of Great Zimbabwe, believed to be built between the 12th and 15th centuries by ancestors of the Shona. The overall shape of the birds suggests that of a bateleur eagle – a bird of great significance in Shona culture. The bateleur or chapungu is a good omen, the symbol of a protective spirit and a messenger of the gods. -

Smallpox

"In Kimberley in 1883-4, several leading doctors with links to the diamond-mining industry publicly denied the presence of smallpox among migrant workers, instead diagnosing them as suffering from a rare skin disease. They appear to have done so lest admitting that the dreaded smallpox was raging, which would have affected the supply of labour and materiel and thereby interrupting mining operations. Led by Cecil Rhodes’s friend, Dr Leander Starr Jameson, measures to curb the epidemic were sporadic or, in the mining compounds, non-existent, and cases topped 2000, with mortality at 3.5 per cent of the population. Only when the colonial government eventually called in external doctors to diagnose the disease, was the cover-up terminated and vaccination, fumigation and isolation vigorously pursued. The conspiracy of denial, by retarding action and sowing doubt about the need to be vaccinated, had been responsible for no small percentage of the 700 deaths in the town" (Phillips 2012: 32-33). -

Chapunga - The day Rhodes fell

The character Msezane is portraying depicts the statue of the Zimbabwe bird that was wrongfully appropriated from Great Zimbabwe by the British colonialist Cecil Rhodes. It currently sits in his Groote Schuur estate. -

What UCT is not telling its first years

On the 19th of January 2015, an article appeared in the Cape Argus titled 'What UCT is not telling its first years' written by Dr Siona O’Connell, a staff member of the Centre for Curating the Archive, and lecturer at the university. In it she wrote about the absence of transformation in the university, evident in its lack of black academic staff, describing the campus as "mired in unarticulated tensions and divisions, many of them pivoting on race” and “guarded by the Rhodes Memorial – a significant imperialist edifice” that continues to shadow it “in many overt and covert ways” "(O’Connell 2015). In the article she pinpoints that even though, as first years, they will most certainly be greeted by the statue of Cecil John Rhodes overlooking the rugby field during their tour of the campus, their chances of being taught by a black professor during the full span of their degree, will be incredibly slim…