Items

Site

The Medicine Chest

Is Part Of is exactly

Biological Sciences

-

Chest: a botanical ecology

Illness and disease affect us all. The treatment of these conditions however, has been vast and varied, depending on the historical periods and the cultural context in and during which they are practiced. Situated in the rock art gallery, where healing power is expressed in San paintings, this mobile set of cabinets explores a rich complex of healing practices through the display of a medicine chest which was donated to the university of Cape Town in 1978. This chest belonged to a British dentist, who practiced in Cape Town from 1904, and who bought the chest for a hunting trip he undertook in 1913 to (then) Northern Rhodesia. The idea of the chest then gives rise to a variety of forms of healing: from instruments used to exorcise evil spirits and children's letters written to celebrate a heart transplant; to medicinal flowers bought at the Adderley Street flower market. The exhibition aims to visualise and materialise illness and its treatment from historical, cultural and disciplinary perspectives. Drawing on well-established historical and contemporary connections between the disciplines of Botany, Medicine and Pharmacology, the exhibits also suggest latent links which are at times political, at times whimsical. -

Foxgloves

Called variously foxgloves, witch’s gloves, dead men’s bells, fairy’s gloves, bloody fingers, gloves of our lady, fairy caps, virgin’s gloves or fairy thimbles, Digitalis purpurea is popular with children, who pluck the tempting bell-shaped blooms and wear them like thimbles, admonished not to lick their fingers afterwards for fear they will go blind (Young 2002: 57). While the flower can be lethal if ingested, the drug digitalis derived from foxglove is most commonly used as a heart stimulant. Digitalis has been prescribed since the 17th century, perhaps earlier, as a diuretic and to slow the pulse and is still the drug of choice for atrial fibrillation. In the 1770s, William Withering got an old family recipe, a herbal infusion for treating swollen legs, from a Shropshire woman and identified digitalis as the active one of the twenty ingredients. Many more antiarrhythmic drugs now exist (Young 2002: 57). Made up of surgical gloves, Band-Aids, syringes and IV-tubing (with an infusion of foxglove leaves in its stem) the work mimicked the language of the herbarium specimen, drawing a viewer in to examine the content they were expecting, only to surprise them with its incongruous materials. -

Eucalyptus

"The plants [dislayed in this cabinet] were bought from the Adderley Street flower market in central Cape Town and are used by the sellers for medicinal purposes to treat chest and respiratory problems, with the leaves of the eucalyptus added to a bath and those of the protea infused in hot water and drunk as a broth. The flower sellers trading in Trafalgar Place and along Adderley Street have been doing so since at least the mid-1880s but became viewed as threats to the local flora by the European settlers at about the same time the medicine chest was first introduced to the city at the beginning of the 20th century. The settlers initially preferred to cultivate plants imported from their home countries to indigenous varieties, introducing many species to South Africa for nostalgic or practical reasons (subsequently problematic for local biodiversity) (Van Sittert 2002: 103). In the wake of emerging white nationalism in the 1890s, interest in indigenous plants gained momentum and was deployed to create a sense of belonging to the ‘foreign’ land (Boehi 2013: 133). A botanical discourse was mobilised to underscore ideas about identity and belonging, such as ‘roots’ and ‘ideas of rootedness’, and laws regulating flower picking (which usually occurred on the mountain) were passed in this period and were secured by the Wild Flower Protections Act in 1905 and an amendment thereto in 1908 (Boehi 2013: 133)"(Liebenberg 2021: 275). -

Proteas

"The plants [dislayed in this cabinet] were bought from the Adderley Street flower market in central Cape Town and are used by the sellers for medicinal purposes to treat chest and respiratory problems, with the leaves of the eucalyptus added to a bath and those of the protea infused in hot water and drunk as a broth. The flower sellers trading in Trafalgar Place and along Adderley Street have been doing so since at least the mid-1880s but became viewed as threats to the local flora by the European settlers at about the same time the medicine chest was first introduced to the city at the beginning of the 20th century. The settlers initially preferred to cultivate plants imported from their home countries to indigenous varieties, introducing many species to South Africa for nostalgic or practical reasons (subsequently problematic for local biodiversity) (Van Sittert 2002: 103). In the wake of emerging white nationalism in the 1890s, interest in indigenous plants gained momentum and was deployed to create a sense of belonging to the ‘foreign’ land (Boehi 2013: 133). A botanical discourse was mobilised to underscore ideas about identity and belonging, such as ‘roots’ and ‘ideas of rootedness’, and laws regulating flower picking (which usually occurred on the mountain) were passed in this period and were secured by the Wild Flower Protections Act in 1905 and an amendment thereto in 1908 (Boehi 2013: 133)" (Liebenberg 2021: 275). -

Forest

"The bottles and pipettes in 'Forest' were originally sourced from the storage rooms of the Chemistry department, where they awaited disposal. This cabinet responded to the lacuna of indigenous material represented by the chest and addressed this imbalance by filling the bottles with teas made from local medicinal plants. Staging the bottles and pipettes to simulate a forest references the prejudice of Burroughs, Wellcome and Co (BWC) against these natural remedies, ‘purifying’ them through laboratory processes before they were deemed trustworthy and marketable. This process also occluded the original source of the remedies and sowed the seeds of biopiracy. The various items of glassware in this cabinet were filled with a selection of infusions made from Balotta africana, Sutherlandia frutescens, Agathosma crenulata, Melianthus major, Mentha longifolia, Petroselinum crispum, Hypoxiz villosa and Salvia officinalis" (Liebenberg 2021: 255). -

The Mother of all Firewalls

'The Mother of all Firewalls' (2012), is a sculptural piece by Kim Gurney made from beeswax, gold glitter, bitumen, repurposed tiles, rabbit skin and glue, which seems to depict an EEG graph in its format but in reality references a graph plotted by Google Insights after Gurney inputted a range of new words that emerged from the ‘Eurogeddon’ of 2012, showing their incidence in news reports pertaining to this financial crisis between 2008 and 2012. -

Where the Wild Things Are (Field study)

'Where the Wild Things Are' (21 October – 5 November 2014) explored the political, social and historical narratives embedded in the natural world through investigation, observation, mapping, archival research and art making. The exhibition consisted of various on-site interventions engaging with contemporary and historical spatial dynamics and the significance of Hiddingh Campus. The Egyptian Building (home to sculpture workshops and studios) was built on the site of a zoo established in the late eighteenth century that was replete with lion’s dens and a small lake that supposedly housed a hippo. The campus was also the home to UCT’s first Zoology and Botany building (now the Michaelis Building). This historical perspective highlights both the site’s colonial imprints and its early affiliation with the sciences. The UCT campus is divided into its main upper campus, a middle and lower campus, and a few satellite campuses, of which the Michaelis School of Fine Art and the South African College of Music form part. Students drew on the methodologies of artist/curator Mark Dion, collaborating with specialists from upper campus (entomologists, ornithologists and botanists) and Michaelis Fine Art students, to highlight its natural environment. The interventions occurred on different days, and over a two week period. A calendar was provided to stipulate event times and artwork appearances. Curated by Nina Liebenberg Participating artists: Christopher Swift, Dillon Marsh, Fritha Langerman, Thuli Gamedze, Pippa Skotnes, Alex Kaczmarek, Rone-Mari Botha, Jessica Holdengarde, Fanie Buys, Lara Reusch, Stephani Muller, Tegan Green, Evan Wigdorowitz, Mariam Moosa, C J Chandler, Adrienne Van Eeden-Wharton -

A 'Jungle'

"A ‘jungle’ consisted of a selection of pathological specimens from the Pathology Learning Centre that had been affected by typhoid fever, ascaris adult worms, yellow fever, amoebic ulcerations, tuberculosis and malaria. The diseases that afflicted these specimens were regarded as ‘tropical’. As described in Chapter One, BWC used the jungle as a significant terrain that called for a medicine chest to combat pathogens: ‘Whether you were valiantly saving your compatriot in war, traversing a dark African jungle, navigating one of the world’s first flying machines, exploring the most desolate place on earth, ascending the highest mountain in the world, or simply enjoying the windswept British coast, the chest would be there, ready for any ailment’ (Johnson 2008b: 255). BWC promoted their chests as the ideal antidote for a tropical landscape ‘at once full of potential wealth for imperial Britain, but simultaneously rife with disease’ (Johnson 2008b: 258) and claimed that the tropical colonies were ‘by far the most dangerous regions for travellers’ (BWC 1934: 8). It was here that ‘desolating ailments’ were encountered, all ‘particularly fatal to the so-called white man who originates in temperate climates’ (BWC 1934: 8). I adapted the colour of the images of afflicted intestines, livers, stomachs and brains and used them as material to construct a dense jungle that referenced this aspect of the medicine chest’s history. Printed on separate glass sections that fit into the cabinet at spaced intervals to create an illusion of depth and three-dimensionality, the work draws on the cross-sectional display technique used in many anatomy museums worldwide, in projects such as the Visible Human Project (1995) and that the artist Damien Hirst references in his works . Creating a visual link between the UCT specimens and the history of these diseases surfaces the occluded racial undertones of these understandings" (Liebenberg 2021: 267). -

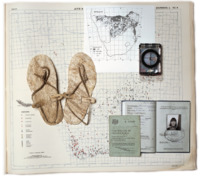

Page 175 of the Curiosity CLXXV catalogue

"The page presents a curated collection of images: a map from the Avian Demography Unit illustrating the distribution of the bataleur Terathopius ecaudatus along the political border, though the bateleur is more frequently found where there is no formal farming; a Ngwato child’s oxhide sandals collected by Isaac Schapera (a British social anthropologist who worked in South Africa and Botswana); a compass; the identification documents of Paula Ensor (previous dean and Professor of Education), who spent time in exile in Botswana; and a Certificate of Registration necessary for movement across borders, all of which are overlaid on top of a large map from the Afrikaans Atlas provided by Rajend Mesthrie of the Department of Linguistics and Southern African Languages that shows the Afrikaans language’s distribution. Contextualising all of these objects in relation to the large map cuts across disciplinary boundaries and illustrates the scope and impact of the colonial and apartheid regimes and their influence on immigration laws, language studies, ornithology and anthropology" (Liebenberg 2021: 193). -

Subtle Thresholds (PLC)

"Integrated into the PLC, these works speak to the specimens on display and provide interesting access points to the collection. The animal-faeces prints (which referenced ‘sites of contamination’ in the context of the SAM exhibition) resonate, for instance, with many of the specimens on display in the PLC, such as the heterotopic heart (also called a ‘piggy-back heart transplant’) created by Dr Chris Barnard in 1977, consisting of a baboon heart grafted onto a human heart for additional motoric support. In addition to their more ‘famous’ specimens, the centre also has an extensive intestinal worm collection and many organs affected by zoonotic diseases, such as a liver ravaged by malaria. This was not a conscious decision on the part of the artist-curator and illustrates how curation can draw attention to aspects of a collection and liberate new associations when brought into conversation with it" (Liebenberg 2021: 201). -

Pages 38-39 of the Curiosity CLXXV catalogue

"Objects and collections can reflect naturalisations that occur when the disciplinary perspective renders its subject matter in terms of what it deems worth looking at and how it should be looked at (Daston & Galison 2007: 23). This process has dual consequences, resulting in the honing of a specialised insider focus directed at the object and a blindness to qualities that sit outside the disciplinary frame of reference (as discussed in relation to the Drennan and Kirby collections). 'Curiosity CLXXV' drew on and challenged both these aspects by forcing objects into visual conversations outside their discipline and inviting insiders to view them in these new configurations. These curatorial strategies enabled insiders to become aware of characteristics not normally deemed important in their discipline and to identify the characteristics their discipline did deem important (their attentional subculture, in other words) in objects not studied in their field" (Liebenberg 2021: 180). -

The Kirby collection of musical instruments

"Kirby’s choice of an ‘age-old simple classification’ to order the instruments can be correlated with another classification formulated at Wits around the time he was collecting. The Department of Bantu Studies was established in the 1920s at roughly the same time as the Music Department. Kirby’s use of the phrase ‘native races’, which features in the title of his book, resonates with the descriptive subtitle of the Wits journal connected to research in this department: Bantu Studies: A Journal Devoted to the Scientific Study of Bantu, Hottentot, and Bushman (Nixon 2013: xii). The homogenising act of categorising all diverse indigenous South African groups into three general categories seems to echo Kirby’s taxonomic imposition on the diverse instruments he collected on his trips and that continues to feature as the ordering principle of this collection" (Liebenberg 2021: 136). -

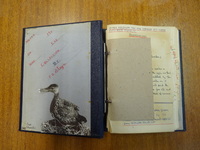

Diary of an oologist

"In 2019, Honours in Curatorship student Nathalie Viruly, who completed her Bachelor of Social Science in Politics and Sociology, was similarly struck by the silence and loss evoked by the [Peter Steyn] collection. Viruly honed in on the moments documented in the notebooks, which capture the loss of life in the reproductive life of these birds and reveal ‘stories of avian tragedy’: Young taken by predator; 1 young accidentally killed; 2 eggs failed to hatch; 2 infertile; Chick disappeared without a trace; Eggs disappeared; Literally cooked by the [corrugated] roof; Nest empty – egg collectors? (Viruly 2018: online). Her focus on these moments in the scientific journal poignantly reveals the conflation between science and emotion and invites the viewer to re-examine hierarchies of loss" (Liebenberg 2021: 219). -

Things zoological insiders look at

A sample box of archaeological specimens shown to first year students. -

Appendix (installation shot)

A variety of pottery shards consisting of Asian porcelain, European earthenware and British stoneware sourced from the University of Cape Town Archaeology department and subjected to a botanical analysis by a graduate of the Biological Science (Botany) Department. -

Appendix (installation shot)

A variety of bones sourced from the University of Cape Town Archaeology and Zoology departments, playfully re-imagined by the students as a collection owned by a time-travelling anthropologist - collecting samples across time and sometimes, across dimensions. -

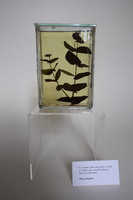

Planthology (detail)

“For 'Planthology (Bulbine frutescens and Lessertia frutescens)' I sourced two medicinal plant specimens from Kirstenbosch National Botanical Garden and x-rayed them at Groote Schuur Hospital (#10 and #13). These two local plants offer a wide variety of healing properties and address the lacuna of the chest. The fresh leaves of the Bulbine frutescens produce a jelly-like juice that can be used for burns, rashes, blisters, insect bites, cracked lips, acne, cold sores, mouth ulcers and areas of cracked skin, while an infusion of these leaves in a cup of boiling water can be taken for coughs, colds and arthritis (Harris 2003: online). The Lessertia frutescens is used as an immune booster in the treatment of HIV/AIDS, as a medicine in the treatment of chicken pox, internal cancers, colds, asthma, TB, bronchitis, rheumatism, rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis, liver problems, haemorrhoids, piles, bladder and uterus problems, diarrhoea, dysentery, stomach ailments, heartburn, peptic ulcers, backache, diabetes, varicose veins and inflammation (Xaba & Notten 2003: online)” (Liebenberg 2021: 269). -

Planthology

In conversation with Dr Yeats in 2011 about adding a few medicinal plants to the centre as part of its displays, she mentioned that no plants survived in there. They all seemed to die from some mysterious cause. I decided to source three medicinal plants, the Lessertia frutescens, Bulbine frutescens and Artemisia afra, and X-ray them to 'diagnose' what might be the cause of their demise. In subjecting the plants to this process and placing the x-ray images in a space that foregrounds the diagnosis of human disease, I intended to create a heterarchical shift in this relationship, considering a world in which the degree of care directed toward human ailments might be replicated in treating diseases manifest in the botanical world. -

Where the Wild Things Are (Installation detail)

WHERE THE WILD THINGS ARE: An Honours in Curatorship Hiddingh Campus field study Curated by Nina Liebenberg 21 OCTOBER – 5 NOVEMBER 2014 'Where the Wild Things Are' explored the political, social and historical narratives embedded in the natural world through investigation, observation, mapping, archival research and art making. The exhibition consisted of various on-site interventions engaging with contemporary and historical spatial dynamics and the significance of Hiddingh Campus. The Egyptian Building (home to sculpture workshops and studios) was built on the site of a zoo established in the late eighteenth century that was replete with lion’s dens and a small lake that supposedly housed a hippo. The campus was also the home to UCT’s first Zoology and Botany building (now the Michaelis Building). This historical perspective highlights both the site’s colonial imprints and its early affiliation with the sciences. The UCT campus is divided into its main upper campus, a middle and lower campus, and a few satellite campuses, of which the Michaelis School of Fine Art and the South African College of Music form part. Students drew on the methodologies of artist/curator Mark Dion, collaborating with specialists from upper campus (entomologists, ornithologists and botanists) and Michaelis Fine Art students, to highlight its natural environment. The interventions occurred on different days, and over a two week period. A calendar was provided to stipulate event times and artwork appearances. Participating artists: Christopher Swift, Dillon Marsh, Fritha Langerman, Thuli Gamedze, Pippa Skotnes, Alex Kaczmarek, Rone-Mari Botha, Jessica Holdengarde, Fanie Buys, Lara Reusch, Stephani Muller, Tegan Green, Evan Wigdorowitz, Mariam Moosa, C J Chandler, Adrienne Van Eeden-Wharton -

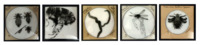

Hosts and Carriers

A selection of glass slides of the insects, ticks and worms that are the primary or intermediate hosts or carriers of human diseases. These slides also featured in the 'Curiosity CLXXV' and 'Subtle thresholds' exhibitions, sourced from the Pathology Learning Centre (PLC), where they were originally donated by the secretary of the Department of Microbiology. Dr Yeats identified them as glass photomicrographs and speculated that they were probably made for a special projector used for teaching many years ago. -

Clivia's in Kirstenbosch

Part of the ‘Useful plants’ section at Kirstenbosch National Botanical Garden. -

Rattles in the Kirby collection

A drawer of rattles in the South African College of Music's Kirby collection: "The instruments are now grouped in different cabinets according to the taxonomy set out by Kirby in his book. In the preface to the second edition (1964), Kirby shares some of his considerations when deciding how to group the instruments, writing that he had to decide ‘whether to arrange his material tribally, or to deal with each type of musical instrument separately from the technological and historical points of view, allowing the tribal aspects to emerge incidentally’ (Kirby 1964: xi). Kirby chose the second alternative, stating that his chief reason was that he wanted the work to be, as far as possible, ‘a complete and comparative study of one particular aspect of the life of our aborigines’ (1964: xi). His second consideration was to find the most suitable manner for classifying the instruments, for which he defaulted to the ‘age-old simple classification of musical instruments into three main groups of percussion, wind and strings’ (1964: xi) – a Western system for the classification of instruments and the principles on which they were based. The chapters in his book and the displays in the room are thus grouped into three categories: percussion – ‘rattles and clappers’, ‘drums’, ‘xylophones and sansas’ and ‘bull-roarers and spinning-disks’; wind instruments – ‘horns and trumpets’, ‘whistles, flutes, and vibrating reeds’ and ‘reed flute ensembles’; and stringed instruments – ‘stringed instruments’ and ‘Bushmen and Hottentot violins and the ramkie’. Kirby encountered one taxonomic anomaly when employing this system: the ‘gora’, an instrument both wind and string, which he termed ‘a stringed-wind instrument’" (Liebenberg 2021: 135). -

The Landis Museum

A drawing by the artist-curator James Hutchinson (Chapter Thirteen) based on an audio description of the object as art of the Glasgow International Arts festival. "Nina Liebenberg also undertakes a form of object analysis at an institutional border. She spent an afternoon in the strongroom of the University of Cape Town's special collections department, examining an early 20th century medicine box commissioned for a hunting trip in (then) Northern Rhodesia. Such boxes had been essential parts of the British colonial project, and allowed emigres, missionaries and explorers to venture deeper into unknown territory without fear of contracting tropical diseases. Liebenberg’s report from the strongroom acts as a set of instructions for The Landis Museum’s curator to make a drawing of the box, to which he has no physical access". Extract from the 'Exhibition Guide' of the Landis Museum (Chapter Thirteen), Glasgow International Arts Festival, 20 April - 07 May 2018. -

Or

"The processes of digression and diversion have much in common with what the writer Ross Chambers (1999) calls ‘loiterature’. Chambers investigates the digressive, category-blurring genre of writing found in works such as Nicholson Baker’s 'The mezzanine', Paul Auster’s 'City of glass' and Laurence Sterne’s 'Tristam Shandy'. Loiterly writing, according to Chambers, disarms criticism by providing a moving target, shifting as its own divided attention constantly shifts. Criticism depends on the opportunity to discriminate and hierarchise, determining what is central and what is peripheral (Chambers 1999: 9), which this form eludes by resisting contextualisation or singular categorisation. Loiterature promotes sites of endless intersection, where attention is always divided between one thing and some other thing, always willing and able to be distracted, contrasting ‘the disciplined and the orderly, the hierarchical and the stable, the methodical and the systematic’ (Chambers 1999: 10). In contrast to methods of science that seek to stabilise objects within taxonomic systems or that require the formulation of hypotheses to provide direction for experimentation and a basis for concrete outcomes, the processes of curatorship and artmaking revel in rerouting and redirecting and in diversion and digression" (Liebenberg 2021: 286). -

'How Zoology was taught in the past'

The wall text accompanying these charts in the Hunterian museum, Glasgow, reads: "In the late 19th and 20th centuries, before the advent of colour slides that could be projected, the teaching of Zoology depended heavily on the use of wall charts to illustrate lectures. They were hung on a special pulley system at the front of the lecture theatre and, because of their large size, could be clearly seen from the back of the class". -

The Heterotopic Hearts

“On two occasions in 1977, when a patient’s left ventricle failed acutely after routine open-heart surgery and when no human donor organ was available, Barnard transplanted an animal heart heterotopically. On the first occasion, a baboon heart was transplanted, but this failed to support the circulation sufficiently, the patient dying some six hours after transplantation. In the second patient, a chimpanzee heart successfully maintained life until irreversible rejection occurred four days later, the recipient’s native heart having failed to recover during this period. Further attempts at xenotransplantation were abandoned and even now, more than 30 years later, xenotransplantation remains an elusive holy grail despite decades of research.” Extract: Brink JG, Hassoulas J. The first human heart transplant and further advances in cardiac transplantation at Groote Schuur Hospital and the University of Cape Town. Cardiovasc J Afr. 2009; 20(1):31-5 -

Dogs in the Heart of Cape Town

The guided tour of the museum, which commemorates the first heart transplant performed by Chris Barnard in 1967, starts with a representation of the car accident that provided the heart for the transplant, through to the animal lab where Barnard conducted experiments with over 50 dogs to perfect the technique of heart transplantation. From there one can tour a model of Denise Darvall's bedroom and Christiaan Barnard's office before seeing a recreation of the surgery in the actual operating theaters where it occurred. -

The Brown Dog Affair (1903 - 1910)

On Feb. 2, 1903, English physicians William Bayliss and Ernest Starling, gave a lecture on the digestive system to a theatre full of medical students. Also in attendance were Lizzy Lind af Hageby and Leisa Schartau, committed feminists and anti-vivisectionists. They had travelled from Sweden to enrol at the London School of Medicine for Women, attend lectures around town, and document the practice of vivisection in British universities. During the lecture, a brown terrier was wheeled out, strapped to a board. Starling had already performed one experiment on the dog two months earlier, shutting off its pancreas. This time, Bayliss cut open the dog’s neck and spent half an hour unsuccessfully trying to stimulate the animal’s salivary glands with electrodes. Eventually, he gave up and handed the dog over to a student (Henry Dale, another future Nobel laureate) who stabbed it through the heart, thus ending the lesson. What followed was a court case filed by Stephen Coleridge, a prominent barrister and secretary of the National Anti-Vivisection Society against Bayliss. After four days of testimony, the judge called the women’s account “hysterical” while giving instructions to the jury. The jurors conferred for 20 minutes, then found Coleridge guilty of libel. Anti-vivisectionists commissioned a bronze statue of the dog as a memorial, unveiled in Battersea in 1906. Its plague, which read "Men and women of England, how long shall these Things be?" led to the it being vandalised on a frequent basis. On 10 December 1907, hundreds of medical students marched through central London waving effigies of the brown dog on sticks, clashing with suffragettes, trade unionists and 300 police officers, one of a series of battles known as the ‘Brown Dog’ riots. In March 1910, tired of the controversy, Battersea Council sent four workers accompanied by 120 police officers to remove the statue under cover of darkness, after which it was reportedly melted down by the council's blacksmith. -

Rats laugh when you tickle them

In 1999, Jaak Panksepp and Jeffrey Burgdorf successfully demonstrated that tickling young rats spurs them into letting out the same ultrasonic giggles they make during play. -

Fish

A showcase of fish found in the Artic regions. -

A label in the Natural History Museum

A label in the Natural History Museum accompanying a discovery made by Mary Anning. -

Your inner fish

"Our hands resemble fossil fins; our heads are organised like those of long extinct jawless fish and major parts of our genomes still look and function like those worms and bacteria" (Shubin 2008). During the summer of his second year of study, paleontologist and evolutionary biologist, Neil Shubin, discovered a particular fossil fish in the Arctic, naming it the Tiktaalik. In Your Inner Fish: A Journey into the 3.5-Billion-Year History of the Human Body (2009) he explored the connections in our human anatomy with those fishes that ventured onto land over 375 million years ago, based on the information gathered from studying the Tiktaalik. -

Of fish and men

The evolution of jaw muscles from fish to men. -

Condensation Cube

"One of Hans Haacke’s earlier works. While over time the artist developed a critique of art as an institution and system, these early works focus on art in the sense of process and physical system. Interested in biology, ecology and cybernetics, in the mid-sixties Haacke was influenced by the ideas of Ludwig von Bertalanffy, especially those outlined in his General System Theory of 1968. For the Austrian biologist and philosopher, a living organism is an open system that continuously changes depending on its dialogue or interaction with the environment. Haacke’s early works, such as Condensation Cube, transpose this concept to the realm of art" (MACBA 2021). -

The Northern Lights

Histology slides of the brain (human and animal), scanned and converted into video projection -

Pompei casts

-

Observing marbling in Edirne

A marbling demonstration observed during a 2012 trip to Istanbul and a visit to the neighbouring Edirne's Health Museum. Opened in Sultan Bayezid II külliye in 1488, the hospital treated patients for over 400 years, until 1909, along the tradition of Turkish-Islamic medicine, which included the treatment of diseases by music. -

Amelia

Amelia explaining her flight plan -

Mary Anning

Henry De la Beche's portrait of Mary Anning, the English fossil collector, dealer, and palaeontologist who became known around the world for finds she made in the cliffs along the English Channel at Lyme Regis. These cliffs consisted of alternating layers of limestone and shale, laid down as sediment on a shallow seabed early in the Jurassic period (about 210 - 195 million years ago). As a woman, Anning was treated as an outsider to the scientific community. The increasingly influential Geological Society of London did not allow women to become members, or even to attend meetings as guests. -

Lotus Leaves (Full Leaf)

"Gabriel Orozco's interest in the natural world and its relationship with humans inspired him to have actual lotus leaves etched into the printing plates, creating a man made yet true rendering of the leaf. Every vein, tear, and insect bite was captured and imprinted on special custom milled Gampi paper matching the hues of the leaf. The proofs were made as chine collé soft ground etchings, individually cut to the shape of each leaf. Orozco had a revelation while holding one of the tissue thin leaf prints up to the window: the exquisite purity that he was seeking was best displayed deconstructed and suspended in glass, illuminated all around, like a delicate specimen. The somewhat unorthodox technique used for this edition was an exciting challenge that resulted in a series of lifelike images that honors the natural world "(Lapis Press 2021). -

Chip of wood from an almond tree

Said to be a chip from the tree under which David Livingstone is said to have proposed to Mary Moffat 1884. Wood chip was donated by R.F. Immelman who purchased it from Kimberley museum. -

Years

“On regular vinyl, there is this groove that represents however long the track is. There’s a physical representation of the length of the audio track that’s imprinted on the record. The year rings are very similar because it takes a very long time to actually grow this structure because it depends on which record you put on of those I made. It’s usually 30 to 60 or 70 years in that amount of space. It was really interesting for me to have this visual representation of time and then translate it back into a song which it wouldn’t originally be " (Traubeck 2012). This record features seven recordings from different Austrian trees. They were generated on the Years installation in Vienna, January 2012. -

Woman, woman, let go of me

In the chapter he titled, 'When Wendy Grew Up', J.M. Barrie recalls how Wendy tried, for Peter’s sake, not to have growing pains – and how she even felt untrue to him when she got the prize for general knowledge. But the years came and went without bringing the careless boy and Wendy eventually grew up and got married. If you feel sorry for her, don’t. Barrie tells us that Wendy was the kind of girl that liked growing up and that in the end, “ she grew up of her own free will a day quicker than other girls” (1989:182). All grown up with a daughter of her own, Peter visits her again one night while she’s sitting in front of the fire, darning. She hears the crow call and the window blows open as of old, Peter dropping to the floor – looking exactly the same as ever. “He was a little boy, and she was grown up. She huddled by the fire not daring to move, helpless and guilty, a big woman. ‘Hallo, Wendy,’ he said, not noticing any difference, for he was thinking chiefly of himself; and in the dim light her dress might have been the nightgown in which he had seen her first. ‘Hallo, Peter,’ she replied faintly, squeezing herself as small as possible. Something inside her was crying, ‘Woman, woman, let go of me’” (1989: 185 - 186). -

The hidden life within

-

Timekeeper

Installation view of a hole revealing all painting of successive exhibition layers, 20 cm in diameter at the Viennese Secession -

Hamish Email

An email between artist-curator and Dr Hamish Robertson. Robertson was invited to Hiddingh campus in his capacity as entomologist (and then Director Natural History Collections at Iziko Museums of South Africa) to assess the environment in terms of biodiversity prior to the staging of the 'Where the Wild Things Are' exhibition. -

Lacuna (Part one)

"It is interesting to note that the botanical origins of most of these medicines were from outside of Africa, especially if one considers the long history of the Cape as a point on the trade routes where ill sailors regularly disembarked and drew on the knowledge of the Khoekhoe traditional healers for treatment and herbal cures (Laidler & Gelfand 1971: 44). The Cape flora offered a plenitude of medicinal resources and these healers (who were skilled in botany, surgery and medicine) used them in a variety of healing practices . The exclusion of local botanical remedies in the BWC No. 254 medicine chest can be attributed to many factors" (Liebenberg 2021: 67). -

Lacuna (Part two)

An ill English Oak on Hiddingh Campus, Michaelis School of Fine Art, University of Cape Town. English oaks were first brought into the country by the early settlers and were one of the first exotic tree species to be planted in South Africa, shortly after Van Riebeek’s arrival in 1652. He explained that in South Africa, these trees do not grow as old as they would have in Europe. The high temperatures cause these trees to grow faster than their species back home, and because of this, their centers start rotting over an extended period of time. The center part of the wood – the heart – is affected by this occurrence and hollowed out over time. -

Forest (process)

A collection of Echinacea angustifolia tea rings read by botanist and dendrochronologist, Dr Edmund February. A molecule found in the Echinacea angustifolia plant prevents a caterpillar on eating it, from ever turning into a butterfly. Example of a specimen reading: “It would appear that the tree stood on a slope since there is more compression on the left hand side, which indicates that side was under less tension. It could also be a branch of which the left hand side would be its underside. The rings are uniformly wide which suggests plenty of soil and moisture availability. In comparison with the other two trees, the outer rings suggest less water or more competition.” -

Forest

A collection of Echinacea angustifolia tea rings read by botanist and dendrochronologist, Dr Edmund February. A molecule found in the Echinacea angustifolia plant prevents a caterpillar on eating it, from ever turning into a butterfly. Example of a specimen reading: “It would appear that the tree stood on a slope since there is more compression on the left hand side, which indicates that side was under less tension. It could also be a branch of which the left hand side would be its underside. The rings are uniformly wide which suggests plenty of soil and moisture availability. In comparison with the other two trees, the outer rings suggest less water or more competition.”