Items

Site

The Medicine Chest

keywords is exactly

botany

-

Chest: a botanical ecology

Illness and disease affect us all. The treatment of these conditions however, has been vast and varied, depending on the historical periods and the cultural context in and during which they are practiced. Situated in the rock art gallery, where healing power is expressed in San paintings, this mobile set of cabinets explores a rich complex of healing practices through the display of a medicine chest which was donated to the university of Cape Town in 1978. This chest belonged to a British dentist, who practiced in Cape Town from 1904, and who bought the chest for a hunting trip he undertook in 1913 to (then) Northern Rhodesia. The idea of the chest then gives rise to a variety of forms of healing: from instruments used to exorcise evil spirits and children's letters written to celebrate a heart transplant; to medicinal flowers bought at the Adderley Street flower market. The exhibition aims to visualise and materialise illness and its treatment from historical, cultural and disciplinary perspectives. Drawing on well-established historical and contemporary connections between the disciplines of Botany, Medicine and Pharmacology, the exhibits also suggest latent links which are at times political, at times whimsical. -

Healing instruments

“I invited Edmund February to the Kirby collection to view the instruments and learn his thoughts on them from a botanical perspective. February identified the dancing rattles as being made of the seed pods of Oncoba spinosa (Venda: mutuzwa) and the seed pod of Adansonia digitata (Venda: muvhuyu). The wood of the iodophone was, however, unrecognisable as a result of its handling. February also contacted colleagues in the Department of Zoology and the School of Mathematical & Natural Sciences at the University of Venda, who connected me to a Venda diviner, Muanalo Dyer, who uses similar baobab rattles (and other materials from that tree) in her healing practices. This interdisciplinary engagement showed that these instruments, supposedly frozen in their early 20th century understanding of being on the brink of extinction, remained very much functional in the present” (Liebenberg 2021: 271). -

The Kirby collection of musical instruments

"Kirby’s choice of an ‘age-old simple classification’ to order the instruments can be correlated with another classification formulated at Wits around the time he was collecting. The Department of Bantu Studies was established in the 1920s at roughly the same time as the Music Department. Kirby’s use of the phrase ‘native races’, which features in the title of his book, resonates with the descriptive subtitle of the Wits journal connected to research in this department: Bantu Studies: A Journal Devoted to the Scientific Study of Bantu, Hottentot, and Bushman (Nixon 2013: xii). The homogenising act of categorising all diverse indigenous South African groups into three general categories seems to echo Kirby’s taxonomic imposition on the diverse instruments he collected on his trips and that continues to feature as the ordering principle of this collection" (Liebenberg 2021: 136). -

Appendix (installation shot)

A variety of pottery shards consisting of Asian porcelain, European earthenware and British stoneware sourced from the University of Cape Town Archaeology department and subjected to a botanical analysis by a graduate of the Biological Science (Botany) Department. -

Rattles in the Kirby collection

A drawer of rattles in the South African College of Music's Kirby collection: "The instruments are now grouped in different cabinets according to the taxonomy set out by Kirby in his book. In the preface to the second edition (1964), Kirby shares some of his considerations when deciding how to group the instruments, writing that he had to decide ‘whether to arrange his material tribally, or to deal with each type of musical instrument separately from the technological and historical points of view, allowing the tribal aspects to emerge incidentally’ (Kirby 1964: xi). Kirby chose the second alternative, stating that his chief reason was that he wanted the work to be, as far as possible, ‘a complete and comparative study of one particular aspect of the life of our aborigines’ (1964: xi). His second consideration was to find the most suitable manner for classifying the instruments, for which he defaulted to the ‘age-old simple classification of musical instruments into three main groups of percussion, wind and strings’ (1964: xi) – a Western system for the classification of instruments and the principles on which they were based. The chapters in his book and the displays in the room are thus grouped into three categories: percussion – ‘rattles and clappers’, ‘drums’, ‘xylophones and sansas’ and ‘bull-roarers and spinning-disks’; wind instruments – ‘horns and trumpets’, ‘whistles, flutes, and vibrating reeds’ and ‘reed flute ensembles’; and stringed instruments – ‘stringed instruments’ and ‘Bushmen and Hottentot violins and the ramkie’. Kirby encountered one taxonomic anomaly when employing this system: the ‘gora’, an instrument both wind and string, which he termed ‘a stringed-wind instrument’" (Liebenberg 2021: 135). -

Lacuna (Part one)

"It is interesting to note that the botanical origins of most of these medicines were from outside of Africa, especially if one considers the long history of the Cape as a point on the trade routes where ill sailors regularly disembarked and drew on the knowledge of the Khoekhoe traditional healers for treatment and herbal cures (Laidler & Gelfand 1971: 44). The Cape flora offered a plenitude of medicinal resources and these healers (who were skilled in botany, surgery and medicine) used them in a variety of healing practices . The exclusion of local botanical remedies in the BWC No. 254 medicine chest can be attributed to many factors" (Liebenberg 2021: 67). -

Lacuna (Part two)

An ill English Oak on Hiddingh Campus, Michaelis School of Fine Art, University of Cape Town. English oaks were first brought into the country by the early settlers and were one of the first exotic tree species to be planted in South Africa, shortly after Van Riebeek’s arrival in 1652. He explained that in South Africa, these trees do not grow as old as they would have in Europe. The high temperatures cause these trees to grow faster than their species back home, and because of this, their centers start rotting over an extended period of time. The center part of the wood – the heart – is affected by this occurrence and hollowed out over time. -

Tobacco Mosaic Virus

During the late 19th century, tobacco farmers observed a strange occurrence on the leaves of their tobacco plants. A mosaic pattern of light and dark green (or yellow and green, in some instances) appeared on the leaves of their crops, the presence of which signalled the steady decline in the plant’s growth. Because of the lucrative nature of the industry, finding a treatment for this seemingly infectious disease became a priority, with many laboratories working to isolate the cause. Bacteria were recognised as the causative agents of many infectious diseases of plants and animals, including humans, in the second half of the 19th century – and the technique of filtration was developed to separate infectious agents from extracts or exudates in order to study these microbes. It was whilst utilising this technique that Dmitri Ivanovski, a Russian microbiologist working in the Crimea in 1890, made a surprising discovery. Using the Chamberland–filter made from porcelain and designed to trap ordinary bacteria, Ivanovsky discovered that the filtered sap from the diseased plants could continue to transfer the infection to healthy plants – an occurrence he attributed to an agent which must be an exceedingly small parasitic microorganism, invisible even under great magnification. It would take another 45 years before the visualisation of this subcellular entity would be formulated with the help of an electron microscope, but Ivanovksy, along with the Dutch botanist M.W. Beijerinck, who also and independently, isolated these microbes in his laboratory in 1898, are generally credited for the discovery of viruses. The disease which infected the tobacco plants would be aptly called the Tobacco Mosaic Virus, and its identification would signal the initiation of a field of study known as virology. -

Resonance

"The revelation of my object-study that the chest was a lacuna in terms of local botanical medicinal remedies and practices served as inspiration for the first department I approached. By engaging with insiders of the Department of Biological Sciences, I reasoned that I could supplement the chest’s Western content with local botanical knowledge. As the first viewing session, it was also the one that initiated the weakening of the chest’s imperial viral load through an inoculation of additional meaning – a treatment with a surprising side-effect. On presenting the chest to other disciplinary insiders afterwards (to Pathology and the College of Music, for example), I noticed characteristics that also resonated with the field of botany within these disciplines and their collections. These botanical resonances accrued as my disciplinary engagements increased and diversified, leading me to embrace this side-effect and to use botany as the central theme of my exhibition. The resonances generated in the different departmental viewing sessions resulted in new links with the chest but also in connections surfacing between disciplines such as zoology, dermatology, pharmacology and sound studies, for example. I drew on these visits and their outcomes to create a range of artworks that materialised the inoculation of the chest by manifesting how intersecting with diverse fields expanded its meaning, and I sourced objects from the collections that encouraged new interpretations" (Liebenberg 2021: 244 - 246). -

Seeds of Change

"'Seeds of Change' is an ongoing investigation based on original research of ballast flora in the port cities of Europe. Projects have been developed for Marseilles, Reposaari, Dunkirk, Exeter and Topsham, Liverpool and Bristol. Material such as stones, earth, sand, wood, bricks and whatever else was economically expedient was used as ballast to stabilize merchant sailing ships according to the weight of the cargo. Upon arrival in port, the ballast was unloaded, carrying with it seeds native to the area where it had been collected. The source of these seeds can be any of the ports and regions (and their regional trading partners) involved in trade with Europe. The botanist, Dr. Heli Jutila, an expert on ballast flora writes, 'Although seeds seem to be dead, they are in fact alive and can remain vital in soil for decades, and even hundreds of years in a state of dormancy'. Seeds contained in ballast soil may germinate and grow, potentially bearing witness to a far more complex narrative of world history than is usually presented by orthodox accounts" (Alves 2021). -

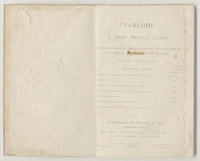

Philosophia Botanica

"'Tabloid' Medicine Chests and Cases and 'Tabloid' First Aid Outfits have become standard equipment for travellers. They have accompanied the pioneers of tropical exploration through the jungles of Equatorial Africa, Asia and South America, as well as travellers to the unknown parts of the temperate zones" (BWC 1934: 12). -

Philosophia Botanica

"'Tabloid' Medicine Chests and Cases and 'Tabloid' First Aid Outfits have become standard equipment for travellers. They have accompanied the pioneers of tropical exploration through the jungles of Equatorial Africa, Asia and South America, as well as travellers to the unknown parts of the temperate zones" (BWC 1934: 12).