Items

Site

The Medicine Chest

keywords is exactly

cabinet

-

Chest: a botanical ecology

Illness and disease affect us all. The treatment of these conditions however, has been vast and varied, depending on the historical periods and the cultural context in and during which they are practiced. Situated in the rock art gallery, where healing power is expressed in San paintings, this mobile set of cabinets explores a rich complex of healing practices through the display of a medicine chest which was donated to the university of Cape Town in 1978. This chest belonged to a British dentist, who practiced in Cape Town from 1904, and who bought the chest for a hunting trip he undertook in 1913 to (then) Northern Rhodesia. The idea of the chest then gives rise to a variety of forms of healing: from instruments used to exorcise evil spirits and children's letters written to celebrate a heart transplant; to medicinal flowers bought at the Adderley Street flower market. The exhibition aims to visualise and materialise illness and its treatment from historical, cultural and disciplinary perspectives. Drawing on well-established historical and contemporary connections between the disciplines of Botany, Medicine and Pharmacology, the exhibits also suggest latent links which are at times political, at times whimsical. -

Livingstone

A small wooden chip from the same object collection as the medicine chest balanced on top of one of the bottles from the chest. "The treatment, the Livingstone rouser, was formulated by Dr Livingstone, who, after an attack of malaria in 1853, patented this mixture of quinine and purgatives (calomel, rhubarb and jalop) mixed with opium (Barrett & Giordani 2017: 1655–1666). The chip balanced on its lid is said to be from the almond tree under which he proposed to Mary Moffat in 1844. The juxtaposition of these two objects, one representing the quantifiable and the other the poetic, draws the viewer to consider the conflation of these two realms" (Liebenberg 2021: 273). -

Healing instruments

“I invited Edmund February to the Kirby collection to view the instruments and learn his thoughts on them from a botanical perspective. February identified the dancing rattles as being made of the seed pods of Oncoba spinosa (Venda: mutuzwa) and the seed pod of Adansonia digitata (Venda: muvhuyu). The wood of the iodophone was, however, unrecognisable as a result of its handling. February also contacted colleagues in the Department of Zoology and the School of Mathematical & Natural Sciences at the University of Venda, who connected me to a Venda diviner, Muanalo Dyer, who uses similar baobab rattles (and other materials from that tree) in her healing practices. This interdisciplinary engagement showed that these instruments, supposedly frozen in their early 20th century understanding of being on the brink of extinction, remained very much functional in the present” (Liebenberg 2021: 271). -

Listen Laennec

"In this work, the temperature graphs of individuals suffering from malaria, yellow fever, trypanosomiasis and tickborne-relapse fever – all viewed as ‘tropical’ and treatable by the contents of the medicine chest – were converted into a musical score. I punched the strips of paper of a hand-cranked musical box mechanism with holes that corresponded to the graphs – the vertical axis representing temperature variations and the horizontal axis representing the approximate number of days the fever is said to last. The translation of these graphs into notes seems nonsensical, as we do not listen for a temperature; we measure it by feeling a forehead or taking a reading with a thermometer. The practice of listening has, however, been part of the history of medicine since the days of Hippocrates (c.460–c.370 BC), when physicians performed auscultations of the lung and heart by placing their ear directly on the patient’s chest' (Liebenberg 2021: 265). -

Broken

"This cabinet displayed a round-bottomed flask that broke during the installation of the exhibition, and which I attempted to mend. The accompanying BWC medicine chest manual highlights the qualities the company wanted to portray as unique to the Tabloid medicine chest and that they believed would set them apart from competitors – such as the longevity of the medicines they sold and the indestructability of the chests (BWC 1925: 2–3). Addressing the supposed indestructability of the chest by focusing specifically on the wide array of glass-stoppered bottles that form a large part of its overall contents and which, according to BWC, ensured the longevity of the medicines, this exhibit displayed a laboratory bottle of similar material, but in a state that demonstrates its fragility. As such, it subverts BWC’s grand claims of indestructability and thereby throws the rest of its claims into doubt" (Liebenberg 2021: 259). -

Forest

"The bottles and pipettes in 'Forest' were originally sourced from the storage rooms of the Chemistry department, where they awaited disposal. This cabinet responded to the lacuna of indigenous material represented by the chest and addressed this imbalance by filling the bottles with teas made from local medicinal plants. Staging the bottles and pipettes to simulate a forest references the prejudice of Burroughs, Wellcome and Co (BWC) against these natural remedies, ‘purifying’ them through laboratory processes before they were deemed trustworthy and marketable. This process also occluded the original source of the remedies and sowed the seeds of biopiracy. The various items of glassware in this cabinet were filled with a selection of infusions made from Balotta africana, Sutherlandia frutescens, Agathosma crenulata, Melianthus major, Mentha longifolia, Petroselinum crispum, Hypoxiz villosa and Salvia officinalis" (Liebenberg 2021: 255). -

A 'Jungle'

"A ‘jungle’ consisted of a selection of pathological specimens from the Pathology Learning Centre that had been affected by typhoid fever, ascaris adult worms, yellow fever, amoebic ulcerations, tuberculosis and malaria. The diseases that afflicted these specimens were regarded as ‘tropical’. As described in Chapter One, BWC used the jungle as a significant terrain that called for a medicine chest to combat pathogens: ‘Whether you were valiantly saving your compatriot in war, traversing a dark African jungle, navigating one of the world’s first flying machines, exploring the most desolate place on earth, ascending the highest mountain in the world, or simply enjoying the windswept British coast, the chest would be there, ready for any ailment’ (Johnson 2008b: 255). BWC promoted their chests as the ideal antidote for a tropical landscape ‘at once full of potential wealth for imperial Britain, but simultaneously rife with disease’ (Johnson 2008b: 258) and claimed that the tropical colonies were ‘by far the most dangerous regions for travellers’ (BWC 1934: 8). It was here that ‘desolating ailments’ were encountered, all ‘particularly fatal to the so-called white man who originates in temperate climates’ (BWC 1934: 8). I adapted the colour of the images of afflicted intestines, livers, stomachs and brains and used them as material to construct a dense jungle that referenced this aspect of the medicine chest’s history. Printed on separate glass sections that fit into the cabinet at spaced intervals to create an illusion of depth and three-dimensionality, the work draws on the cross-sectional display technique used in many anatomy museums worldwide, in projects such as the Visible Human Project (1995) and that the artist Damien Hirst references in his works . Creating a visual link between the UCT specimens and the history of these diseases surfaces the occluded racial undertones of these understandings" (Liebenberg 2021: 267). -

Isigubu through Gqom

"In 2018, the Zulu drum alleged to have been played during the 1906 Bambatha rebellion against British rule and unfair taxation in the colony of Natal (discussed by Nixon) became the focus of Amogelang Maledu’s Honours research project. In ‘Isigubu through gqom: The sound of defiance and Black joy’, Maledu (who has an undergraduate degree in Anthropology and Visual Culture) used the drum’s history of colonial resistance and contextualised it through the contemporary musical genre of gqom, showing music as both an act and celebration of joy and freedom and of defiance against the limitations of township life. Through her ‘speculative and imagined interconnectedness’ of the isigubu and gqom, Maledu appropriated the limited information available about the former and expanded it by reinventing new historical pathways that reframed colonial narrations and aesthetics (Maledu 2018: 29–30). Her curation broke the silence of the Kirby instruments and liberated the isigubu from its ethnomusicological framework through a juxtaposition that spoke back to history and the contemporary moment. In addition, a website provides a framework for historicising gqom and encouraged the growth of its archive through viewer engagement, also highlighting the speculative and stagnant colonial archive in which the isigubu is situated (Maledu 2018: 29–30)" (Liebenberg 2021: 211 - 212). -

Miscast (installation detail)

Instruments from the Kirby collection displayed as part of the 'Miscast' exhibition. -

The Kirby collection of musical instruments

"Kirby’s choice of an ‘age-old simple classification’ to order the instruments can be correlated with another classification formulated at Wits around the time he was collecting. The Department of Bantu Studies was established in the 1920s at roughly the same time as the Music Department. Kirby’s use of the phrase ‘native races’, which features in the title of his book, resonates with the descriptive subtitle of the Wits journal connected to research in this department: Bantu Studies: A Journal Devoted to the Scientific Study of Bantu, Hottentot, and Bushman (Nixon 2013: xii). The homogenising act of categorising all diverse indigenous South African groups into three general categories seems to echo Kirby’s taxonomic imposition on the diverse instruments he collected on his trips and that continues to feature as the ordering principle of this collection" (Liebenberg 2021: 136). -

Miscast (Lane reflects)

"Where viewers had to walk over a floor of vinyl tiles printed with photocopied newspaper articles and photographs of the San, Lane reflected on another archaeological parallel: ‘just as the texts and images on the floor represent the debris of a particular history, so too do the artefacts strewn across the surface of a site’ (Lane 1996: 7). Yet in trying to define sites and their history, archaeologists feel ‘they can tread on the debris of their own or others’ ancestors with equanimity, colonizing that space for themselves’ (Lane 1996: 7)" (Liebenberg 2021: 172 - 174). -

Miscast (installation detail)

"In juxtaposing instruments that are still being used (such as the scalpel and the camera) with ones that are not (the Von Luschan skin colour chart and the anthropometric measuring rods), Skotnes set up an opportunity for science to reflect on its past and on the activities and objects of its present, enabling a mode of self-reflexivity that is not a standard part of its day-to-day practices. Through curatorship, she exposed disciplinary practitioners to naturalisations and blind spots within their fields and sensitised them to these previously occluded characteristics" (Liebenberg 2021: 172). -

Diary of an oologist

"In 2019, Honours in Curatorship student Nathalie Viruly, who completed her Bachelor of Social Science in Politics and Sociology, was similarly struck by the silence and loss evoked by the [Peter Steyn] collection. Viruly honed in on the moments documented in the notebooks, which capture the loss of life in the reproductive life of these birds and reveal ‘stories of avian tragedy’: Young taken by predator; 1 young accidentally killed; 2 eggs failed to hatch; 2 infertile; Chick disappeared without a trace; Eggs disappeared; Literally cooked by the [corrugated] roof; Nest empty – egg collectors? (Viruly 2018: online). Her focus on these moments in the scientific journal poignantly reveals the conflation between science and emotion and invites the viewer to re-examine hierarchies of loss" (Liebenberg 2021: 219). -

Rattles in the Kirby collection

A drawer of rattles in the South African College of Music's Kirby collection: "The instruments are now grouped in different cabinets according to the taxonomy set out by Kirby in his book. In the preface to the second edition (1964), Kirby shares some of his considerations when deciding how to group the instruments, writing that he had to decide ‘whether to arrange his material tribally, or to deal with each type of musical instrument separately from the technological and historical points of view, allowing the tribal aspects to emerge incidentally’ (Kirby 1964: xi). Kirby chose the second alternative, stating that his chief reason was that he wanted the work to be, as far as possible, ‘a complete and comparative study of one particular aspect of the life of our aborigines’ (1964: xi). His second consideration was to find the most suitable manner for classifying the instruments, for which he defaulted to the ‘age-old simple classification of musical instruments into three main groups of percussion, wind and strings’ (1964: xi) – a Western system for the classification of instruments and the principles on which they were based. The chapters in his book and the displays in the room are thus grouped into three categories: percussion – ‘rattles and clappers’, ‘drums’, ‘xylophones and sansas’ and ‘bull-roarers and spinning-disks’; wind instruments – ‘horns and trumpets’, ‘whistles, flutes, and vibrating reeds’ and ‘reed flute ensembles’; and stringed instruments – ‘stringed instruments’ and ‘Bushmen and Hottentot violins and the ramkie’. Kirby encountered one taxonomic anomaly when employing this system: the ‘gora’, an instrument both wind and string, which he termed ‘a stringed-wind instrument’" (Liebenberg 2021: 135). -

Curiosity CLXXV

Hiddingh Hall during the construction of the installation of Curiosity CLXXV. -

Hiddingh Hall

Hiddingh Hall prior to the installation of Curiosity CLXXV. -

Miscast (instruments of measurement)

"Along with the guides that regulated practices and protocols to stabilise and standardise an individual’s response to unfamiliar and disorienting sights (Kennedy 2013: 42), the gender, class and ethnicity of the observer were also of importance , as was the use of ‘ever more sophisticated instruments and calculations designed to minimize the intrusion of subjectivity into the reporting of information’ (Driver 2001: 55). By regulating who was doing the viewing, stipulating what should be viewed and how and supplying tools to measure these observations, scientific institutions promoted an authoritative ‘way of seeing’ in the field that differentiated the scientific view from that of the ordinary traveller (Driver 2001: 49)" (Liebenberg 2021: 109). -

175 chalk-board dusters

For the exhibition, 'Curiosity CLXXV', the curators took an old duster from each teaching venue and replaced it with a new one. -

Iroko

Structurally, 'Chest: a botanical ecology' consisted of 15 modular interlocking cabinets of differing sizes which rested on top of one another, making up the front of the display. These were constructed from two types of wood, the darker iroko wood, and a lighter ash wood – with the iroko originating from the repurposed cabinets used for Curiosity CLXXV in 2004. The Iroko tree is a large hardwood tree from the west coast of tropical Africa, known by the Yoruba as ìrókò, logo or loko. Believed to have supernatural properties, it can live up to 500 years. Yoruba people believe that a spirit inhabits the tree, and anybody who sees the Iroko-man face to face becomes insane and dies. According to the Yoruba, any man who cuts down any Iroko tree causes devastating misfortune on himself and all of his family. In West Africa, the iroko wood is also used to make the djembe drum. If they however, need to cut down the tree, they can make a prayer afterwards to protect themselves. Used for a variety of purposes including boat-building, domestic flooring, furniture and outdoor gates, from the late 1990s, it was also used as part of the txalaparta, a Basque musical instrument constructed of wooden boards, due to its lively sound and classified as an idiophone (a percussion instrument) (Ogumfe 1929: online)). -

Notebooks 2 – Nest Records

"'Notebook 2 – Nest Records' is part of the Peter Steyn Collection at the Percy Fitzpatrick Institute of African Ornithology (PFIAO) at the University of Cape Town. It resides in the top drawer of a wooden cabinet that is locked and stained with nepheline. The drawer is shared with two other notebooks created by Steyn, the first from his youth, and the latter is focused on birds of prey. It lies beside a copy of Frank B. Smithe’s Naturalist’s Color Guide, a published article by Steyn, two printed documents, attached letters and an envelope of reference photographs. The subsequent drawers are filled with an array of labelled, blown, eggs. Pink. Blue. Burnt-copper. Speckled. Splattered" (Viruly 2019). -

Prrrip-Prrrip, Tseeeep!: the silence of birds’ eggs

"Birds are highly vocal creatures, their songs sound everyday in almost every habitat, even our concrete cities. These calls have been likened to the human capacity for speech, yet the faculty of language has, for most of history, been described as solely ‘human.’ Language forms one of several traits deployed to uphold the constructed divide between human and non-human animals. Oology – the collecting and documenting of wild bird eggs – was an obscure hobby and ‘science’ of the past. Collected eggs were pierced and ‘blown’ of their contents. The perfect shells, beautifully coloured with speckles and intricate patterns, were then placed in vast cabinet collections. Such a birds’ egg collection, collected in Southern Africa during the last half of the 20th century, forms the starting point of this exhibition. Through exploring language and communication in birds, this exhibition aims to create an affective environment for re-evaluating the collecting practices of the past (with its ties to the Euro-Western, human-centered perspective), and for re-imagining current natural history collections. It also aims to … poo-too-eee poo-too-eee, pa-chip-chip-chip per chick-a-ree. Ka-ha, ka-ha, kuh-uk-uk-uk! caw-caw-caw-caw-koodle-yah, loooooo-eee! Pa-chip-chip-chip, per-chick-a-ree!" Wall text of exhibition, Prrrip-Prrrip, Tseeeep!: the silence of birds’ eggs -

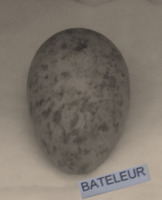

Bataleur egg

Situated in a locked bespoke cabinet in the Niven Library in UCT’s Percy Fitzgerald Institute of African Ornithology, this Bataleur eagle egg is part of a collection of eggs donated by the ornithologist Peter Steyn in 2007. Collected between 1961 and 1977, when Steyn spent time in Zimbabwe, the egg is a link to the iconic stone carved Zimbabwe Birds which once stood proudly on guard atop the walls and monoliths of the ancient city of Great Zimbabwe, believed to be built between the 12th and 15th centuries by ancestors of the Shona. The overall shape of the birds suggests that of a bateleur eagle – a bird of great significance in Shona culture. The bateleur or chapungu is a good omen, the symbol of a protective spirit and a messenger of the gods.