Items

Site

The Medicine Chest

keywords is exactly

history

-

Taxonomy

Visually categorising a selection of my research material (accumulated since 2015). -

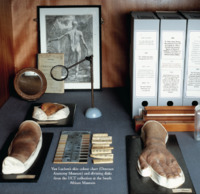

Healing instruments

“I invited Edmund February to the Kirby collection to view the instruments and learn his thoughts on them from a botanical perspective. February identified the dancing rattles as being made of the seed pods of Oncoba spinosa (Venda: mutuzwa) and the seed pod of Adansonia digitata (Venda: muvhuyu). The wood of the iodophone was, however, unrecognisable as a result of its handling. February also contacted colleagues in the Department of Zoology and the School of Mathematical & Natural Sciences at the University of Venda, who connected me to a Venda diviner, Muanalo Dyer, who uses similar baobab rattles (and other materials from that tree) in her healing practices. This interdisciplinary engagement showed that these instruments, supposedly frozen in their early 20th century understanding of being on the brink of extinction, remained very much functional in the present” (Liebenberg 2021: 271). -

Where the Wild Things Are (Field study)

'Where the Wild Things Are' (21 October – 5 November 2014) explored the political, social and historical narratives embedded in the natural world through investigation, observation, mapping, archival research and art making. The exhibition consisted of various on-site interventions engaging with contemporary and historical spatial dynamics and the significance of Hiddingh Campus. The Egyptian Building (home to sculpture workshops and studios) was built on the site of a zoo established in the late eighteenth century that was replete with lion’s dens and a small lake that supposedly housed a hippo. The campus was also the home to UCT’s first Zoology and Botany building (now the Michaelis Building). This historical perspective highlights both the site’s colonial imprints and its early affiliation with the sciences. The UCT campus is divided into its main upper campus, a middle and lower campus, and a few satellite campuses, of which the Michaelis School of Fine Art and the South African College of Music form part. Students drew on the methodologies of artist/curator Mark Dion, collaborating with specialists from upper campus (entomologists, ornithologists and botanists) and Michaelis Fine Art students, to highlight its natural environment. The interventions occurred on different days, and over a two week period. A calendar was provided to stipulate event times and artwork appearances. Curated by Nina Liebenberg Participating artists: Christopher Swift, Dillon Marsh, Fritha Langerman, Thuli Gamedze, Pippa Skotnes, Alex Kaczmarek, Rone-Mari Botha, Jessica Holdengarde, Fanie Buys, Lara Reusch, Stephani Muller, Tegan Green, Evan Wigdorowitz, Mariam Moosa, C J Chandler, Adrienne Van Eeden-Wharton -

Isigubu through Gqom

"In 2018, the Zulu drum alleged to have been played during the 1906 Bambatha rebellion against British rule and unfair taxation in the colony of Natal (discussed by Nixon) became the focus of Amogelang Maledu’s Honours research project. In ‘Isigubu through gqom: The sound of defiance and Black joy’, Maledu (who has an undergraduate degree in Anthropology and Visual Culture) used the drum’s history of colonial resistance and contextualised it through the contemporary musical genre of gqom, showing music as both an act and celebration of joy and freedom and of defiance against the limitations of township life. Through her ‘speculative and imagined interconnectedness’ of the isigubu and gqom, Maledu appropriated the limited information available about the former and expanded it by reinventing new historical pathways that reframed colonial narrations and aesthetics (Maledu 2018: 29–30). Her curation broke the silence of the Kirby instruments and liberated the isigubu from its ethnomusicological framework through a juxtaposition that spoke back to history and the contemporary moment. In addition, a website provides a framework for historicising gqom and encouraged the growth of its archive through viewer engagement, also highlighting the speculative and stagnant colonial archive in which the isigubu is situated (Maledu 2018: 29–30)" (Liebenberg 2021: 211 - 212). -

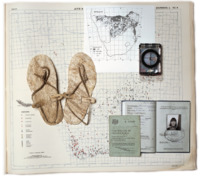

Page 175 of the Curiosity CLXXV catalogue

"The page presents a curated collection of images: a map from the Avian Demography Unit illustrating the distribution of the bataleur Terathopius ecaudatus along the political border, though the bateleur is more frequently found where there is no formal farming; a Ngwato child’s oxhide sandals collected by Isaac Schapera (a British social anthropologist who worked in South Africa and Botswana); a compass; the identification documents of Paula Ensor (previous dean and Professor of Education), who spent time in exile in Botswana; and a Certificate of Registration necessary for movement across borders, all of which are overlaid on top of a large map from the Afrikaans Atlas provided by Rajend Mesthrie of the Department of Linguistics and Southern African Languages that shows the Afrikaans language’s distribution. Contextualising all of these objects in relation to the large map cuts across disciplinary boundaries and illustrates the scope and impact of the colonial and apartheid regimes and their influence on immigration laws, language studies, ornithology and anthropology" (Liebenberg 2021: 193). -

Pages 38-39 of the Curiosity CLXXV catalogue

"Objects and collections can reflect naturalisations that occur when the disciplinary perspective renders its subject matter in terms of what it deems worth looking at and how it should be looked at (Daston & Galison 2007: 23). This process has dual consequences, resulting in the honing of a specialised insider focus directed at the object and a blindness to qualities that sit outside the disciplinary frame of reference (as discussed in relation to the Drennan and Kirby collections). 'Curiosity CLXXV' drew on and challenged both these aspects by forcing objects into visual conversations outside their discipline and inviting insiders to view them in these new configurations. These curatorial strategies enabled insiders to become aware of characteristics not normally deemed important in their discipline and to identify the characteristics their discipline did deem important (their attentional subculture, in other words) in objects not studied in their field" (Liebenberg 2021: 180). -

Etching from 'Sound from the Thinking Strings'

"Skotnes’s own visual interpretation of the history and cosmology of the |xam formed the last component of this interdisciplinary endeavour and constituted a visual component that drew together the various strands of disciplinary interpretations and presented a perspective on the |xam life she felt ‘was missing from the other interpretations’ (Skotnes 1991: 30). In these images she drew freely on San mythology, accounts of |xam life recorded by Lucy Lloyd, historical and archaeological research and images from rock paintings in a landscape setting. She writes in her preface that these etchings were direct attempts at ‘inverting the museum dioramas’ in the ethnographic halls close to the exhibition and which, through their display of the San’s body casts, rendered them closer to specimens of biology than as members of a highly developed culture (Skotnes 1991: 52). By creating images that combined shamanistic rituals, entoptic spirals, plants, hunting bags, bows and arrows, snakes, eland-shaped rainclouds, colonists, musical instruments, shelters and therianthropic shapes, Skotnes eclipsed the static narratives of the dioramas and the object labels in the exhibition, placing them in a context in which their metaphysical qualities were celebrated more than their physical qualities. These prints stood in striking contrast to the other exhibits, which framed the San as physical types, and they challenged viewers to confront the reality that the San had a rich history and cultural and social life" (Liebenberg 2021: 157). -

Sound from the Thinking Strings (installation detail)

"Skotnes had a longstanding relationship with the museum, which started when she was still a student at the Michaelis School of Fine Art. Davison remembers that Skotnes would visit the taxidermy section of the South African museum to draw bones. As an anthropologist, Davison admits to finding Skotnes’s way of looking at things stimulating – an individual way of looking at objects that made her look at them differently, even though she was already very familiar with these materials. Davison recalls a visit to the ethnographic stores during which she showed Skotnes the San skin bags, carefully conserved in their drawers and laid out on acid-free paper. Skotnes admired not only their aesthetic qualities but related the stories she had been studying in the Bleek and Lloyd archive to them – stories that shifted their status from anthropological museum objects to powerful animate objects in San spiritual and social life (P. Davison, personal communication, 28 January 2021). Skotnes remembers that she asked staff whether they knew what was inside the bags and was shocked when nobody could remember looking in them. She was allowed to look inside one and found a claw, which they thought must be a leopard’s (P. Skotnes, personal communication, 9 May 2021)" (Liebenberg 2021: 2015). -

Page 135 of the Curiosity CLXXV catalogue

"Peering into one of them could, for instance, reveal musical instruments from the South African College of Music’s Kirby collection; old wooden mathematical models of abaci and polyhedrons from the Maths department; mobiles demonstrating platonic solids made by mechanical engineering students; publications by a UCT Professor of Astronomy; a sign pointing to ward D10 from the old section of Groote Schuur Hospital; glass slides once used as a teaching aid for art history at Michaelis; bird ringing material from the Avian Demography unit; and a bottle-brush plant labelled by the son of one of the curators" (Liebenberg 2021: 179). -

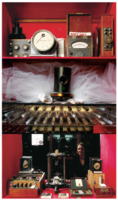

The Kirby collection of musical instruments

"Kirby’s choice of an ‘age-old simple classification’ to order the instruments can be correlated with another classification formulated at Wits around the time he was collecting. The Department of Bantu Studies was established in the 1920s at roughly the same time as the Music Department. Kirby’s use of the phrase ‘native races’, which features in the title of his book, resonates with the descriptive subtitle of the Wits journal connected to research in this department: Bantu Studies: A Journal Devoted to the Scientific Study of Bantu, Hottentot, and Bushman (Nixon 2013: xii). The homogenising act of categorising all diverse indigenous South African groups into three general categories seems to echo Kirby’s taxonomic imposition on the diverse instruments he collected on his trips and that continues to feature as the ordering principle of this collection" (Liebenberg 2021: 136). -

Miscast (Lane reflects)

"Where viewers had to walk over a floor of vinyl tiles printed with photocopied newspaper articles and photographs of the San, Lane reflected on another archaeological parallel: ‘just as the texts and images on the floor represent the debris of a particular history, so too do the artefacts strewn across the surface of a site’ (Lane 1996: 7). Yet in trying to define sites and their history, archaeologists feel ‘they can tread on the debris of their own or others’ ancestors with equanimity, colonizing that space for themselves’ (Lane 1996: 7)" (Liebenberg 2021: 172 - 174). -

Page 65 of the Curiosity CLXXV catalogue

Page 65 of the 'Curiosity CLXXV' catalogue, showing the Old Anatomy Lecture Theatre (currently part of the Centre for Curating the Archive). -

Page 79 of the Curiosity CLXXV catalogue.

"Created by Felix von Luschan, an Austrian doctor, anthropologist, explorer, archaeologist and ethnographer in the early 20th century, the chart, known as the Von Luschan chromatic scale (...) was used to classify skin colour and featured as a tool in race studies and anthropometry of the time. Forgotten by its current department staff and students, its presence draws attention to the role of medicine and science in the apartheid agenda and to the larger racist scientific practices of measuring and classifying human physical differences in the 19th and 20th centuries to produce a ‘typology of race’ (Sturken & Cartwright 2018: 351–352). To support such theories, object collections in scientific university departments worldwide also featured collections of human remains; tools for measuring the size and shape of skulls; and charts detailing various physiognomic features (Sturken & Cartwright 2018: 351 – 352)" (Liebenberg 2021: 122 - 125). -

Hoard

"The chest was featured in a work titled 'Hoard', for which Bloch sculpted in clay the objects in the UCT collection as well as ones from the 11th century Mapungubwe collection (housed at the University of Pretoria). She painted these sculpted objects gold and presented them in museum display cases, drawing attention to the arbitrary nature of objects’ value and to the possibility that historically loaded items can be accidentally overlooked and misevaluated (Bloch in Honigman 2014: online)" (Liebenberg 2021: 82 - 84). -

Capitance

"Strategies such as juxtapositioning also served to highlight poetic and emotive qualities in fields not known for encouraging them, as in a cabinet curated by Langerman titled Capitance. This featured a range of instruments from the Physics department used to measure electrical currents (galvanometers, capacitors and Wheatstone bridges); a crystal goniometer measuring crystal face angles and crystal 175 from the crystal collection in Geological Sciences; M.R. Drennan’s models of the human embryo and a wax model of flesh; and a white tutu from the School of Ballet. In combining this selection of scientific instruments with a tutu, Langerman made allowance for the materials to be considered in a more poetic light, inviting the viewer to consider how a grand jeté defies the laws of physics, for example" (Liebenberg 2021: 186). -

Similitude

"In 'Similitude', Langerman brought together a selection of objects from three disparate disciplines – glassware from chemical engineering; a skull with an arrow embedded in it and a torch used as a murder weapon from forensic pathology; and two flutes from the Kirby collection. Ignoring the assigned functions the objects performed within their respective disciplines, she chose instead to use their formal characteristics as a taxonomic device. They were all, as she described them, ‘long thin things’ (Langerman n.d.). In displacing these objects from their respective disciplines and positioning them in proximity to objects that shared this new category, she neutralised their disciplinary functions and flattened their meanings within those fields (Langerman n.d.)" (Liebenberg 2021: 183). -

A display on page 97 of the Curiosity CLXXV catalogue

"A stainless-steel dilator from the Drennan collection, a carded set of glass slides of xenopus heart sections from the Medical Microbiology collection, a 19th century game called 'Frogs and Toads' from Special Collections and a wax model of an embryo, also from Drennan. This ‘amphibian’-inspired display showcases many qualities of the curatorial method, such as visual quotation (the combination of these materials foregrounds that the shape of the dilator resembles a frog), analogy (the wax embryo, dilator and frogs allude to the resemblance between sperm and tadpoles) and juxtaposition (the frog as a scientific topic dissected and contained in the slides, and the frog as a board piece in a game played by children)" (Liebenberg 2021: 183). -

Fools and other stories

My copy of Ndebele’s 'Fools and other stories', read and underlined in 2001. -

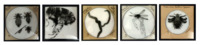

Hosts and Carriers

A selection of glass slides of the insects, ticks and worms that are the primary or intermediate hosts or carriers of human diseases. These slides also featured in the 'Curiosity CLXXV' and 'Subtle thresholds' exhibitions, sourced from the Pathology Learning Centre (PLC), where they were originally donated by the secretary of the Department of Microbiology. Dr Yeats identified them as glass photomicrographs and speculated that they were probably made for a special projector used for teaching many years ago. -

A teeth mould guide

"The large quantity of papers in the BC666 collection pertaining to dental matters – which includes ‘legal and financial papers of the dental practice, papers of the various dental societies to which Walter belonged from 1905 to 1934’ and letters on various dental matters, as well as a large section devoted to correspondence, memoranda and notes on the Medical, Dental and Pharmacy Act of 1928 – shows he was ‘very active in dental politics’ (Hart & Lydall 1981: 1). As an 'office-bearing member of the Dental Society of the Cape Province, and a member of the South African Dental Association, he was the key figure in formulating and presenting the dentists’ case against unqualified dental mechanics in the proposed new medical bill, which was passed in 1928 as the Medical, Dental and Pharmacy Act' (Hart & Lydall 1981: 1). This act was considered a milestone in the development of organised medical, dental and pharmaceutical practices in South Africa, establishing a single set of regulations for these professions across the country (Ryan 1986: 149–151). It was also, however, one of a series of laws passed in South Africa that have regulated indigenous medical practices since the 19th century. Legislation passed in 1862 prevented sangomas from practicing (Paarl in Bishop 2010: 14), and the 1928 act barred inyangas from practicing in all parts of the country except Natal, where they could continue to practice if granted a license (Flint in Bishop 2010: 14–15). The act also banned the indigenous use of ‘European’ methods of diagnosis and treatment, for example forbidding the use of stethoscopes by inyangas (Bishop 2010: 16)" (Liebenberg 2021: 53 - 55). -

Rattles in the Kirby collection

A drawer of rattles in the South African College of Music's Kirby collection: "The instruments are now grouped in different cabinets according to the taxonomy set out by Kirby in his book. In the preface to the second edition (1964), Kirby shares some of his considerations when deciding how to group the instruments, writing that he had to decide ‘whether to arrange his material tribally, or to deal with each type of musical instrument separately from the technological and historical points of view, allowing the tribal aspects to emerge incidentally’ (Kirby 1964: xi). Kirby chose the second alternative, stating that his chief reason was that he wanted the work to be, as far as possible, ‘a complete and comparative study of one particular aspect of the life of our aborigines’ (1964: xi). His second consideration was to find the most suitable manner for classifying the instruments, for which he defaulted to the ‘age-old simple classification of musical instruments into three main groups of percussion, wind and strings’ (1964: xi) – a Western system for the classification of instruments and the principles on which they were based. The chapters in his book and the displays in the room are thus grouped into three categories: percussion – ‘rattles and clappers’, ‘drums’, ‘xylophones and sansas’ and ‘bull-roarers and spinning-disks’; wind instruments – ‘horns and trumpets’, ‘whistles, flutes, and vibrating reeds’ and ‘reed flute ensembles’; and stringed instruments – ‘stringed instruments’ and ‘Bushmen and Hottentot violins and the ramkie’. Kirby encountered one taxonomic anomaly when employing this system: the ‘gora’, an instrument both wind and string, which he termed ‘a stringed-wind instrument’" (Liebenberg 2021: 135). -

Silver Particle / Bronze (After Henry Moore).

"In Simon Starling’s work, inanimate objects are activated in various ways, especially when their political or economic history is revealed or when their materiality becomes an embodiment of something discovered during his research. His work enables and celebrates diverse interpretations of objects in many instances, as Greenblatt (1991) notes when referring to artistic and curatorial activity, deflecting attention away from the object onto the systems that gave rise to it in the first place. Starling conducts a close inspection of his objects, usually following a web of connections across the globe and across history, which in many of his works lead him back to the starting point; a vintage photograph of a Henry Moore sculpture leads to the production of a bronze sculpture based on the shape of a single enlarged silver particle that makes up the photograph and which, when converted into a sculpture, resembles the biomorphic shapes that served as inspiration for the Moore sculpture in the original vintage photograph ('Silver particle/bronze (after Henry Moore)', 2008). The machinations of its history somehow lost in the image when seen in the museum archive come back into play through the translations and reconstructions encountered in the detour and are materialised in the exhibition format" (Liebenberg 2021: 26 - 28). -

The South African College

“UCT was founded in 1829 as the South African College, a high school for boys. The College had a small tertiary-education facility that grew substantially after 1880, when the discovery of gold and diamonds in the north – and the resulting demand for skills in mining – gave it the financial boost it needed to grow. The College developed into a fully fledged university during the period 1880 to 1900, thanks to increased funding from private sources and the government. During these years, the College built its first dedicated science laboratories, and started the departments of mineralogy and geology to meet the need for skilled personnel in the country's emerging diamond and gold-mining industries” (University of Cape Town 2021). -

Hamish Email

An email between artist-curator and Dr Hamish Robertson. Robertson was invited to Hiddingh campus in his capacity as entomologist (and then Director Natural History Collections at Iziko Museums of South Africa) to assess the environment in terms of biodiversity prior to the staging of the 'Where the Wild Things Are' exhibition. -

Forest (process)

A collection of Echinacea angustifolia tea rings read by botanist and dendrochronologist, Dr Edmund February. A molecule found in the Echinacea angustifolia plant prevents a caterpillar on eating it, from ever turning into a butterfly. Example of a specimen reading: “It would appear that the tree stood on a slope since there is more compression on the left hand side, which indicates that side was under less tension. It could also be a branch of which the left hand side would be its underside. The rings are uniformly wide which suggests plenty of soil and moisture availability. In comparison with the other two trees, the outer rings suggest less water or more competition.” -

Forest

A collection of Echinacea angustifolia tea rings read by botanist and dendrochronologist, Dr Edmund February. A molecule found in the Echinacea angustifolia plant prevents a caterpillar on eating it, from ever turning into a butterfly. Example of a specimen reading: “It would appear that the tree stood on a slope since there is more compression on the left hand side, which indicates that side was under less tension. It could also be a branch of which the left hand side would be its underside. The rings are uniformly wide which suggests plenty of soil and moisture availability. In comparison with the other two trees, the outer rings suggest less water or more competition.” -

Pattern recognition

A display in Groote Schuur Hospital, Cape Town. The label reads: The History of Crockery Apartheid did more than separate the races. Parallel with the separate crockery for the different religions (Jewish = Blue; Muslim = Pink) was a range of separate crockery for the staff and patients of different races. Here are a few examples of this complex collection: Royal Blue: Jewish patients and staff (kosher) Dark Navy Blue: "European" patients Green: "European" staff Maroon: "Non European" patients Black: "Non European" staff Pink: Muslim patients and staff (halaal) These pieces of crockery are now part of our history and all patients are served meals in the standard rectangular crocker plate. -

1975 (Invasive Species)

1975 (Invasive Species) stems from a historical and botanical enquiry. In 1975, after attaining independence from Portugal, the civil war broke out in Angola. In that same year, the South African Defense Force under the authorization of Vorster, intervened in the war – an intervention which formed part of an ongoing period of conflict in South African history, known as the Border Wars. From a botanical point of departure, the cluster pine (or Pinus Pinaster) is native to Portugal. In South Africa it is seen as invasive, competing with and replacing indigenous species. The work consists of a cross section of cluster pine used as a target practice unit, into which the artist shot a ring of R4 assault rifle bullets – aiming at tree ring 1975.