Items

Site

The Medicine Chest

keywords is exactly

identity

-

Eucalyptus

"The plants [dislayed in this cabinet] were bought from the Adderley Street flower market in central Cape Town and are used by the sellers for medicinal purposes to treat chest and respiratory problems, with the leaves of the eucalyptus added to a bath and those of the protea infused in hot water and drunk as a broth. The flower sellers trading in Trafalgar Place and along Adderley Street have been doing so since at least the mid-1880s but became viewed as threats to the local flora by the European settlers at about the same time the medicine chest was first introduced to the city at the beginning of the 20th century. The settlers initially preferred to cultivate plants imported from their home countries to indigenous varieties, introducing many species to South Africa for nostalgic or practical reasons (subsequently problematic for local biodiversity) (Van Sittert 2002: 103). In the wake of emerging white nationalism in the 1890s, interest in indigenous plants gained momentum and was deployed to create a sense of belonging to the ‘foreign’ land (Boehi 2013: 133). A botanical discourse was mobilised to underscore ideas about identity and belonging, such as ‘roots’ and ‘ideas of rootedness’, and laws regulating flower picking (which usually occurred on the mountain) were passed in this period and were secured by the Wild Flower Protections Act in 1905 and an amendment thereto in 1908 (Boehi 2013: 133)"(Liebenberg 2021: 275). -

Proteas

"The plants [dislayed in this cabinet] were bought from the Adderley Street flower market in central Cape Town and are used by the sellers for medicinal purposes to treat chest and respiratory problems, with the leaves of the eucalyptus added to a bath and those of the protea infused in hot water and drunk as a broth. The flower sellers trading in Trafalgar Place and along Adderley Street have been doing so since at least the mid-1880s but became viewed as threats to the local flora by the European settlers at about the same time the medicine chest was first introduced to the city at the beginning of the 20th century. The settlers initially preferred to cultivate plants imported from their home countries to indigenous varieties, introducing many species to South Africa for nostalgic or practical reasons (subsequently problematic for local biodiversity) (Van Sittert 2002: 103). In the wake of emerging white nationalism in the 1890s, interest in indigenous plants gained momentum and was deployed to create a sense of belonging to the ‘foreign’ land (Boehi 2013: 133). A botanical discourse was mobilised to underscore ideas about identity and belonging, such as ‘roots’ and ‘ideas of rootedness’, and laws regulating flower picking (which usually occurred on the mountain) were passed in this period and were secured by the Wild Flower Protections Act in 1905 and an amendment thereto in 1908 (Boehi 2013: 133)" (Liebenberg 2021: 275). -

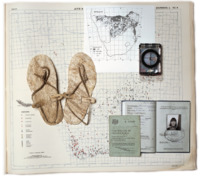

Page 175 of the Curiosity CLXXV catalogue

"The page presents a curated collection of images: a map from the Avian Demography Unit illustrating the distribution of the bataleur Terathopius ecaudatus along the political border, though the bateleur is more frequently found where there is no formal farming; a Ngwato child’s oxhide sandals collected by Isaac Schapera (a British social anthropologist who worked in South Africa and Botswana); a compass; the identification documents of Paula Ensor (previous dean and Professor of Education), who spent time in exile in Botswana; and a Certificate of Registration necessary for movement across borders, all of which are overlaid on top of a large map from the Afrikaans Atlas provided by Rajend Mesthrie of the Department of Linguistics and Southern African Languages that shows the Afrikaans language’s distribution. Contextualising all of these objects in relation to the large map cuts across disciplinary boundaries and illustrates the scope and impact of the colonial and apartheid regimes and their influence on immigration laws, language studies, ornithology and anthropology" (Liebenberg 2021: 193). -

Pages 38-39 of the Curiosity CLXXV catalogue

"Objects and collections can reflect naturalisations that occur when the disciplinary perspective renders its subject matter in terms of what it deems worth looking at and how it should be looked at (Daston & Galison 2007: 23). This process has dual consequences, resulting in the honing of a specialised insider focus directed at the object and a blindness to qualities that sit outside the disciplinary frame of reference (as discussed in relation to the Drennan and Kirby collections). 'Curiosity CLXXV' drew on and challenged both these aspects by forcing objects into visual conversations outside their discipline and inviting insiders to view them in these new configurations. These curatorial strategies enabled insiders to become aware of characteristics not normally deemed important in their discipline and to identify the characteristics their discipline did deem important (their attentional subculture, in other words) in objects not studied in their field" (Liebenberg 2021: 180). -

The workshop

"Held in the Department of Human Biology in the Division of Clinical Anatomy and Biological Anthropology, this collection consists of prepared specimens – both bottled and plastinated, anatomical models – and a skeletal repository used for research purposes. The materials are kept in three separate rooms, with the anatomical models in one, the prepared and plastinated specimens in another and the skeleton repository in its own room behind locked doors, viewable by appointment only. The room housing the anatomical models functioned as a workshop when modelmaking was still offered to first year medical students as an elective course: its walls are lined with shelves that display models made from materials ranging from papier-mâché to modern silicon copies and are taxonomised according to their anatomical representations, such as ‘the eye’, ‘head & neck’, ‘dentistry’, ‘embryology’, ‘lungs’ and ‘cardiovascular system’, to name a few. The models represent each anatomical section and are brightly coloured to differentiate the different parts of the human body and aid in identification. Many of the models can be dismantled into separate pieces and, like a puzzle, be reassembled into their original shapes. Interspersed with these models are rolled-up charts depicting organs, bodily systems and anatomical sections of the body in two-dimensional form, as well as old student modelling projects. A selection of animal skeletons is displayed on the far side of the room, and a shelf with a few anatomical specimens in formaldehyde is across from it" (Liebenberg 2021: 121 - 122). -

Falling stars

Marine biologists studying whalesharks use the pattern-recognition technique, developed in 1986, that astronomers use to analyze data from the Hubble Space Telescope. Studying the spatial relationships between a whaleshark's spots form the basis for creating a unique identifier for each shark. -

#165317 Dipsy

In 2015, Conservation International scientists in Indonesia attached satellite transmitters to the dorsal fins of whale sharks to learn more about their migratory movements and diving behavior. Dipsy, a 4.57-meter male, spent much of his 17-month deployment in Triton Bay but also visited the Aru and Kei Islands – one of our first Kaimana whale sharks to explore the Arafura Sea – before returning to Kaimana. He hit a maximum depth of 625 meters. -

#165321 Yoda

In 2015, Conservation International scientists in Indonesia attached satellite transmitters to the dorsal fins of whale sharks to learn more about their migratory movements and diving behavior. Yoda had a lengthy 26-month deployment, spending all of that time in Cendrawasih Bay. The 4.83-meter male dove to a maximum depth of 1,375 meters, reaching the bottom of the bay at one of its deepest points. -

#151097 Fijubeca

In 2015, Conservation International scientists in Indonesia attached satellite transmitters to the dorsal fins of whale sharks to learn more about their migratory movements and diving behavior. At just 3 meters in length (about 10 feet), Fijubeca logged an impressive 9,000 kilometers (5,592 miles) during his deployment. He visited eight of the Bird’s Head Seascape's marine protected areas (MPAs), reaffirming the placement of MPAs as related to megafauna migratory routes. -

#168184 Sunbridge

In 2015, Conservation International scientists in Indonesia attached satellite transmitters to the dorsal fins of whale sharks to learn more about their migratory movements and diving behavior. Sunbridge was one of our first sharks tagged in Saleh Bay, Sumbawa, where he spent his entire 14-month deployment. Though this 6.23-meter male spent a fair bit of time on the surface, he frequently visited the bay's bottom at a maximum depth of 350 meters. -

#165905 Sebastian

In 2015, Conservation International scientists in Indonesia attached satellite transmitters to the dorsal fins of whale sharks to learn more about their migratory movements and diving behavior. Sebastian spent most of his 27-month deployment in Cendrawasih Bay but also recorded a visit to the Mapia atoll and ventured past Biak into PNG coastal waters. He eventually returned to Cendrawasih, where his tag's battery expired, having logged a maximum dive of 1,125 meters.