Items

Site

The Medicine Chest

keywords is exactly

indigenous

-

Eucalyptus

"The plants [dislayed in this cabinet] were bought from the Adderley Street flower market in central Cape Town and are used by the sellers for medicinal purposes to treat chest and respiratory problems, with the leaves of the eucalyptus added to a bath and those of the protea infused in hot water and drunk as a broth. The flower sellers trading in Trafalgar Place and along Adderley Street have been doing so since at least the mid-1880s but became viewed as threats to the local flora by the European settlers at about the same time the medicine chest was first introduced to the city at the beginning of the 20th century. The settlers initially preferred to cultivate plants imported from their home countries to indigenous varieties, introducing many species to South Africa for nostalgic or practical reasons (subsequently problematic for local biodiversity) (Van Sittert 2002: 103). In the wake of emerging white nationalism in the 1890s, interest in indigenous plants gained momentum and was deployed to create a sense of belonging to the ‘foreign’ land (Boehi 2013: 133). A botanical discourse was mobilised to underscore ideas about identity and belonging, such as ‘roots’ and ‘ideas of rootedness’, and laws regulating flower picking (which usually occurred on the mountain) were passed in this period and were secured by the Wild Flower Protections Act in 1905 and an amendment thereto in 1908 (Boehi 2013: 133)"(Liebenberg 2021: 275). -

Proteas

"The plants [dislayed in this cabinet] were bought from the Adderley Street flower market in central Cape Town and are used by the sellers for medicinal purposes to treat chest and respiratory problems, with the leaves of the eucalyptus added to a bath and those of the protea infused in hot water and drunk as a broth. The flower sellers trading in Trafalgar Place and along Adderley Street have been doing so since at least the mid-1880s but became viewed as threats to the local flora by the European settlers at about the same time the medicine chest was first introduced to the city at the beginning of the 20th century. The settlers initially preferred to cultivate plants imported from their home countries to indigenous varieties, introducing many species to South Africa for nostalgic or practical reasons (subsequently problematic for local biodiversity) (Van Sittert 2002: 103). In the wake of emerging white nationalism in the 1890s, interest in indigenous plants gained momentum and was deployed to create a sense of belonging to the ‘foreign’ land (Boehi 2013: 133). A botanical discourse was mobilised to underscore ideas about identity and belonging, such as ‘roots’ and ‘ideas of rootedness’, and laws regulating flower picking (which usually occurred on the mountain) were passed in this period and were secured by the Wild Flower Protections Act in 1905 and an amendment thereto in 1908 (Boehi 2013: 133)" (Liebenberg 2021: 275). -

The workshop

"Held in the Department of Human Biology in the Division of Clinical Anatomy and Biological Anthropology, this collection consists of prepared specimens – both bottled and plastinated, anatomical models – and a skeletal repository used for research purposes. The materials are kept in three separate rooms, with the anatomical models in one, the prepared and plastinated specimens in another and the skeleton repository in its own room behind locked doors, viewable by appointment only. The room housing the anatomical models functioned as a workshop when modelmaking was still offered to first year medical students as an elective course: its walls are lined with shelves that display models made from materials ranging from papier-mâché to modern silicon copies and are taxonomised according to their anatomical representations, such as ‘the eye’, ‘head & neck’, ‘dentistry’, ‘embryology’, ‘lungs’ and ‘cardiovascular system’, to name a few. The models represent each anatomical section and are brightly coloured to differentiate the different parts of the human body and aid in identification. Many of the models can be dismantled into separate pieces and, like a puzzle, be reassembled into their original shapes. Interspersed with these models are rolled-up charts depicting organs, bodily systems and anatomical sections of the body in two-dimensional form, as well as old student modelling projects. A selection of animal skeletons is displayed on the far side of the room, and a shelf with a few anatomical specimens in formaldehyde is across from it" (Liebenberg 2021: 121 - 122). -

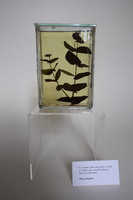

Planthology (detail)

“For 'Planthology (Bulbine frutescens and Lessertia frutescens)' I sourced two medicinal plant specimens from Kirstenbosch National Botanical Garden and x-rayed them at Groote Schuur Hospital (#10 and #13). These two local plants offer a wide variety of healing properties and address the lacuna of the chest. The fresh leaves of the Bulbine frutescens produce a jelly-like juice that can be used for burns, rashes, blisters, insect bites, cracked lips, acne, cold sores, mouth ulcers and areas of cracked skin, while an infusion of these leaves in a cup of boiling water can be taken for coughs, colds and arthritis (Harris 2003: online). The Lessertia frutescens is used as an immune booster in the treatment of HIV/AIDS, as a medicine in the treatment of chicken pox, internal cancers, colds, asthma, TB, bronchitis, rheumatism, rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis, liver problems, haemorrhoids, piles, bladder and uterus problems, diarrhoea, dysentery, stomach ailments, heartburn, peptic ulcers, backache, diabetes, varicose veins and inflammation (Xaba & Notten 2003: online)” (Liebenberg 2021: 269). -

Planthology

In conversation with Dr Yeats in 2011 about adding a few medicinal plants to the centre as part of its displays, she mentioned that no plants survived in there. They all seemed to die from some mysterious cause. I decided to source three medicinal plants, the Lessertia frutescens, Bulbine frutescens and Artemisia afra, and X-ray them to 'diagnose' what might be the cause of their demise. In subjecting the plants to this process and placing the x-ray images in a space that foregrounds the diagnosis of human disease, I intended to create a heterarchical shift in this relationship, considering a world in which the degree of care directed toward human ailments might be replicated in treating diseases manifest in the botanical world. -

‘Mrs Glover attending to an ill African chief.’

"The figure of ‘Mrs Glover’, kneeling and treating what appears to be a very ill man, exudes not only the authority of Western medicine within the local context but conveys her as the self-sacrificing and caring European ‘civilizer’ in service of expanding the empire, ‘the medicine chest conveniently by her side’ (Johnson 2008b: 259)" (Liebenberg 2021: 63 - 65). -

A teeth mould guide

"The large quantity of papers in the BC666 collection pertaining to dental matters – which includes ‘legal and financial papers of the dental practice, papers of the various dental societies to which Walter belonged from 1905 to 1934’ and letters on various dental matters, as well as a large section devoted to correspondence, memoranda and notes on the Medical, Dental and Pharmacy Act of 1928 – shows he was ‘very active in dental politics’ (Hart & Lydall 1981: 1). As an 'office-bearing member of the Dental Society of the Cape Province, and a member of the South African Dental Association, he was the key figure in formulating and presenting the dentists’ case against unqualified dental mechanics in the proposed new medical bill, which was passed in 1928 as the Medical, Dental and Pharmacy Act' (Hart & Lydall 1981: 1). This act was considered a milestone in the development of organised medical, dental and pharmaceutical practices in South Africa, establishing a single set of regulations for these professions across the country (Ryan 1986: 149–151). It was also, however, one of a series of laws passed in South Africa that have regulated indigenous medical practices since the 19th century. Legislation passed in 1862 prevented sangomas from practicing (Paarl in Bishop 2010: 14), and the 1928 act barred inyangas from practicing in all parts of the country except Natal, where they could continue to practice if granted a license (Flint in Bishop 2010: 14–15). The act also banned the indigenous use of ‘European’ methods of diagnosis and treatment, for example forbidding the use of stethoscopes by inyangas (Bishop 2010: 16)" (Liebenberg 2021: 53 - 55). -

Seeing

Educational models found in the Anatomy workshop: "Borrowing from Herbert Read’s art historical discussion on looking, Digby posits that the biomedical practitioner’s generally critical attitudes were shaped in part by their limited recognition of indigenous medicine during this period – ‘what we see is inseparable from how we see; the eye is not innocent, and vision is partial’ (Digby 2006: 356) and, quoting Read, ‘we see what we learn to see, and vision becomes a habit, a convention, a partial selection of all there is to see’ (in Digby 2006: 356). Accordingly, Digby argues that the Western practitioners would have had, at best, only a partial view of the different medical systems in South Africa during this period (Digby 2006: 357) and probably only to the extent that it was a threat to their own livelihood and authority – as evidenced in the 1928 Medical, Dental and Pharmacy Act that Floyd helped instate" (Liebenberg 2021: 55). -

Lacuna (Part one)

"It is interesting to note that the botanical origins of most of these medicines were from outside of Africa, especially if one considers the long history of the Cape as a point on the trade routes where ill sailors regularly disembarked and drew on the knowledge of the Khoekhoe traditional healers for treatment and herbal cures (Laidler & Gelfand 1971: 44). The Cape flora offered a plenitude of medicinal resources and these healers (who were skilled in botany, surgery and medicine) used them in a variety of healing practices . The exclusion of local botanical remedies in the BWC No. 254 medicine chest can be attributed to many factors" (Liebenberg 2021: 67). -

Lacuna (Part two)

An ill English Oak on Hiddingh Campus, Michaelis School of Fine Art, University of Cape Town. English oaks were first brought into the country by the early settlers and were one of the first exotic tree species to be planted in South Africa, shortly after Van Riebeek’s arrival in 1652. He explained that in South Africa, these trees do not grow as old as they would have in Europe. The high temperatures cause these trees to grow faster than their species back home, and because of this, their centers start rotting over an extended period of time. The center part of the wood – the heart – is affected by this occurrence and hollowed out over time. -

Dis-Location/Re-Location

Farber's research examines themes of adaptation to new surroundings and circumstances through the real-life persona of Bertha Guttmann, a Jewish woman brought to South Africa from Sheffield in 1885 at the age of 22. She entered into an arranged marriage with Sammy Marks, who rose from being a peddler to one of the old Transvaal Republic’s leading industrialists. They lived in a beautiful home, now a museum, called Zwartkoppies, east of Pretoria. "Rather, from the initial cut, she inserts a seedling aloe into her flesh, delicately ‘planting’ the indigenous South African succulent into her forearm. This action represents a physical grafting of an alien botanical life form into the “lily-white corpus of Europe” (Ord 2008:106)" (Farber 2012: 35). Bertha Marks’s construction of the formal English rose garden on the ‘moral wastes’ of the Highveld could be recognised as part of a broader colonial project to ‘civilise’ the ‘barbaric’ African land. The road leading to the eastern gate of Zwartkoppies is lined with Eucalyptus trees planted by Sammy Marks. Rather as in his wife’s attempt to create her formal rose garden in her new surroundings and in so doing to ‘tame’ nature, Sammy Marks embarked on an ambitious campaign to “reclaim” and “green” Zwartkoppies, “creating a civilised landscape out of what his secretary called a wilderness” (Mendelsohn 1991:104). Thousands of trees were planted, mainly exotic varieties such as pines and blue gums, as well as orchards and vineyards (Mendelsohn 1991:104)" (Farber 2012: 58) -

Seeds of Change

"'Seeds of Change' is an ongoing investigation based on original research of ballast flora in the port cities of Europe. Projects have been developed for Marseilles, Reposaari, Dunkirk, Exeter and Topsham, Liverpool and Bristol. Material such as stones, earth, sand, wood, bricks and whatever else was economically expedient was used as ballast to stabilize merchant sailing ships according to the weight of the cargo. Upon arrival in port, the ballast was unloaded, carrying with it seeds native to the area where it had been collected. The source of these seeds can be any of the ports and regions (and their regional trading partners) involved in trade with Europe. The botanist, Dr. Heli Jutila, an expert on ballast flora writes, 'Although seeds seem to be dead, they are in fact alive and can remain vital in soil for decades, and even hundreds of years in a state of dormancy'. Seeds contained in ballast soil may germinate and grow, potentially bearing witness to a far more complex narrative of world history than is usually presented by orthodox accounts" (Alves 2021). -

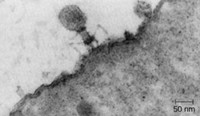

Holes

A virus attacks a cell by attaching itself to the outer wall. It then uses a specialized protein to digest a small hole in the wall of the cell and inject its nucleic acid molecule into the cell's cytoplasm. -

Holes

The landscape of the Karoo and the Northern Cape – the land of the |xam – is rich with holes in the ground. Below the surface of the earth burrowing animals navigate their way through the roots of grasses and shrubs, small trees and creepers. Holes are made and inhabited by scorpions and spiders, mice and shrews, suricats and mongooses. One of the most energetic of burrowers is the anteater whose holes, in places, transform the landscape. Anteaters are such active diggers and their holes so numerous that abandoned burrows are quickly occupied by bat-eared foxes, hyenas, hares, civets, bats, jackals, owls and porcupines (Skotnes 2010: 26)