Philosophia Botanica

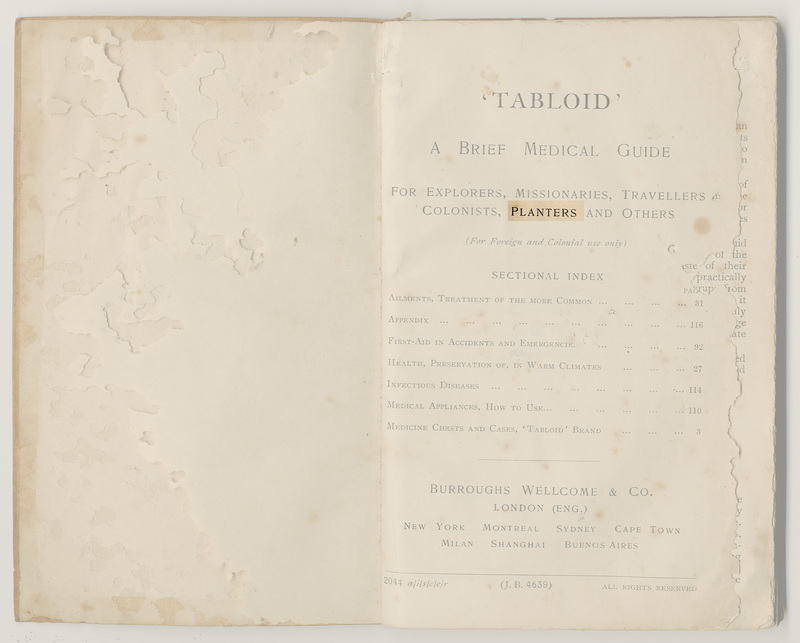

An extract from the Tabloid textbook serves as the starting point for this curriculum and initiates the connection between the chest and the themed subject matter presented. Entries are drawn from the larger depository of materials for this curriculum and each entry builds on the previous one in an associative manner and should be carefully considered, before moving on to the next item.

"'Seeds of Change' is an ongoing investigation based on original research of ballast flora in the port cities of Europe. Projects have been developed for Marseilles, Reposaari, Dunkirk, Exeter and Topsham, Liverpool and Bristol. Material such as stones, earth, sand, wood, bricks and whatever else was economically expedient was used as ballast to stabilize merchant sailing ships according to the weight of the cargo. Upon arrival in port, the ballast was unloaded, carrying with it seeds native to the area where it had been collected. The source of these seeds can be any of the ports and regions (and their regional trading partners) involved in trade with Europe.

The botanist, Dr. Heli Jutila, an expert on ballast flora writes, 'Although seeds seem to be dead, they are in fact alive and can remain vital in soil for decades, and even hundreds of years in a state of dormancy'. Seeds contained in ballast soil may germinate and grow, potentially bearing witness to a far more complex narrative of world history than is usually presented by orthodox accounts" (Alves 2021).

Farber's research examines themes of adaptation to new surroundings and circumstances through the real-life persona of Bertha Guttmann, a Jewish woman brought to South Africa from Sheffield in 1885 at the age of 22. She entered into an arranged marriage with Sammy Marks, who rose from being a peddler to one of the old Transvaal Republic’s leading industrialists. They lived in a beautiful home, now a museum, called Zwartkoppies, east of Pretoria.

"Rather, from the initial cut, she inserts a seedling aloe into her flesh, delicately ‘planting’ the indigenous South African succulent into her forearm. This action represents a physical grafting of an alien botanical life form into the “lily-white corpus of Europe” (Ord 2008:106)" (Farber 2012: 35).

Bertha Marks’s construction of the formal English rose garden on the ‘moral wastes’ of the Highveld could be recognised as part of a broader colonial project to ‘civilise’ the ‘barbaric’ African land. The road leading to the eastern gate of Zwartkoppies is lined with Eucalyptus trees planted by Sammy Marks. Rather as in his wife’s attempt to create her formal rose garden in her new surroundings and in so doing to ‘tame’ nature, Sammy Marks embarked on an ambitious campaign to “reclaim” and “green” Zwartkoppies, “creating a civilised landscape out of what his secretary called a wilderness” (Mendelsohn 1991:104). Thousands of trees were planted, mainly exotic varieties such as pines and blue gums, as well as orchards and vineyards (Mendelsohn 1991:104)" (Farber 2012: 58)

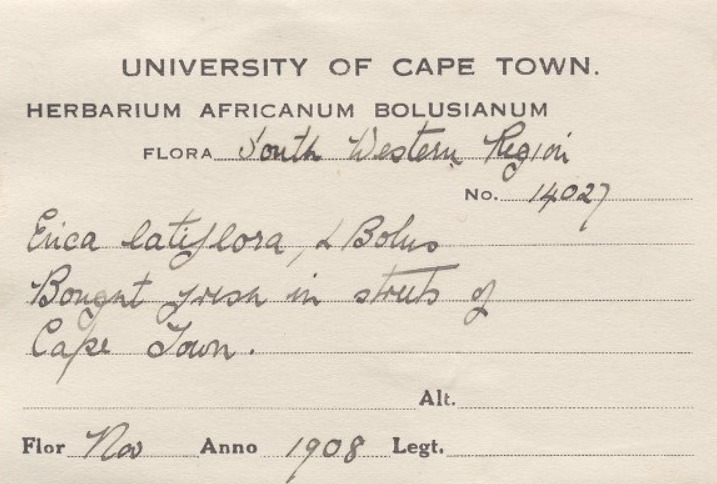

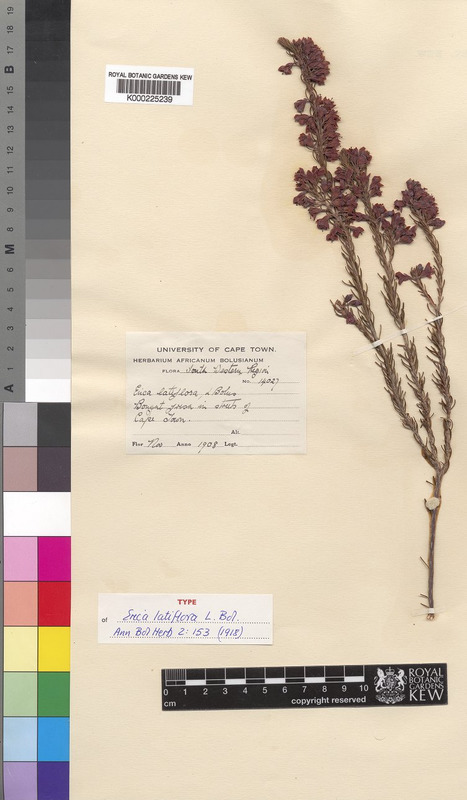

"The flower sellers trading in Trafalgar Place and along Adderley Street in central Cape Town, have been doing so since at least the mid–1880s. A botanical specimen (K000225239) found in the Royal Botanic Gardens of Kew that was donated to them by the University of Cape Town. Written in pen in the notes section, the specimen is of the local Erica Latiflora and was collected in 1908, when it was “bought fresh in the streets of Cape Town”. The insider details noted on this specimen therefore has much to reveal to outsiders, such as Boehi (2013) and Van Sittert (2010), scholars who have written about the colonial history of botany in the Cape and the unofficial presence of these flower sellers in the provenance of many of the specimens kept in these international herbariums that came from the Cape " (Liebenberg 2021: 275).

During the late 19th century, tobacco farmers observed a strange occurrence on the leaves of their tobacco plants. A mosaic pattern of light and dark green (or yellow and green, in some instances) appeared on the leaves of their crops, the presence of which signalled the steady decline in the plant’s growth. Because of the lucrative nature of the industry, finding a treatment for this seemingly infectious disease became a priority, with many laboratories working to isolate the cause. Bacteria were recognised as the causative agents of many infectious diseases of plants and animals, including humans, in the second half of the 19th century – and the technique of filtration was developed to separate infectious agents from extracts or exudates in order to study these microbes. It was whilst utilising this technique that Dmitri Ivanovski, a Russian microbiologist working in the Crimea in 1890, made a surprising discovery.

Using the Chamberland–filter made from porcelain and designed to trap ordinary bacteria, Ivanovsky discovered that the filtered sap from the diseased plants could continue to transfer the infection to healthy plants – an occurrence he attributed to an agent which must be an exceedingly small parasitic microorganism, invisible even under great magnification. It would take another 45 years before the visualisation of this subcellular entity would be formulated with the help of an electron microscope, but Ivanovksy, along with the Dutch botanist M.W. Beijerinck, who also and independently, isolated these microbes in his laboratory in 1898, are generally credited for the discovery of viruses.

The disease which infected the tobacco plants would be aptly called the Tobacco Mosaic Virus, and its identification would signal the initiation of a field of study known as virology.

"During the period known as tulipmania which transpired in the Netherlands during the 17th century, contract prices for bulbs of the recently introduced tulip reached extraordinarily high levels and then suddenly collapsed. Tulips that displayed a break in their colour reached prices far higher than those that didn’t. It wasn’t until 1920, after the invention of the electron microscope, that scientists discovered that the cause for this symphony of colour was a virus that spread from tulip to tulip by Myzus persicae, the peach potato aphid.

Michael Pollan in 'The Botany of Desire', explains this phenomenon: “The colour of a tulip consists of two pigments working in concert — a base colour that is always yellow or white and a second, laid-on colour called an anthocyanin; the mix of these two hues determining the unitary colour we see. The virus works by partially and irregularly suppressing the anthocyanin, thereby allowing a portion of the underlying colour to show through — creating the magic of the broken tulip. A fact that, as soon as it was discovered, doomed the beauty it had made possible" (Pollan 2003: 97 in Liebenberg 2011: 92).

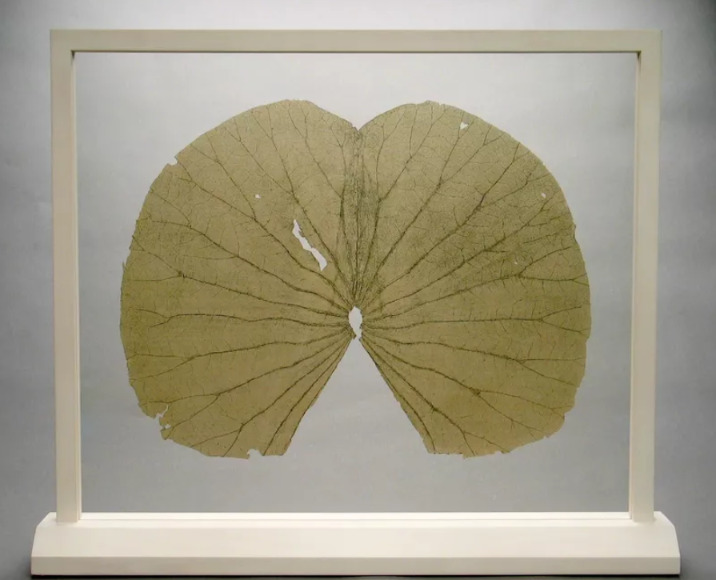

"I collected leaves from the gardens surrounding Groote Schuur Hospital, and subjected them to an analysis by UCT dermatologist, Dr Ranks Lehloenya . Using my strategy of directing the insider gaze on an outsider object, Lehloenya treated these specimens as if they were sections of skin and read them accordingly, highlighting sections which showed signs of nummular eczema, acne, aging, miliary tuberculosis and melanoma, to name a few" (Liebenberg 2021: 277).

Linnaeus’s ways of looking at and describing, depicting, and classifying plants in the 18th century, were very influential for the construction of the types of images used in the scientific atlases of the time. Daston and Galison describes this process as “openly, even aggressively selective” (2007: 59) with botanists training themselves to concentrate on characteristics that were “constant, certain and organic”; and to not be distracted by irrelevant details of a plant’s appearance and thereby unnecessarily multiply species. Botanists had to also prevent their illustrators from rendering “accidental traits, like colour, as opposed to essential ones, like number, form, proportion, and position” (2007: 59).

"This section shows characteristics which could point at various causes. The darker raised sections could be blackheads as seen in acne (note the darker central area reminiscent of an open pore); villous hair cysts ( a condition in which hair follicles are trapped under the skin to form pimple-like structures with the hair giving a dark hue in the centre; syringomas (non-cancerous proliferation of sweat glands); infections such as chicken pox or miliary tuberculosis in which the infection spreads from the blood onto the skin (miliary mean it looks like a millet seed). It could also be metastatic melanoma that has spread from another area onto this skin".

Pattern recognition in Groote Schuur Hospital, Cape Town. The label of this display reads as follows:

The History of Crockery

Apartheid did more than separate the races. Parallel with the separate crockery for the different religions (Jewish = Blue; Muslim = Pink) was a range of separate crockery for the staff and patients of different races. Here are a few examples of this complex collection:

Royal Blue: Jewish patients and staff (kosher)

Dark Navy Blue: "European" patients

Green: "European" staff

Maroon: "Non European" patients

Black: "Non European" staff

Pink: Muslim patients and staff (halaal)

These pieces of crockery are now part of our history and all patients are served meals in the standard rectangular crocker plate.

NOV 8, 2018 AT 8:32PM

Extract from an email from Dr Ranks Lehloenya:

I actually thought of inviting you to an open session with the Dermatology registrars for an hour, there are twelve of them, and get them to go through a similar exercise as I did before coming to the exhibition independent of each other. All you would need to do is to project the images on the screen and they can write their thoughts on paper for you to keep and digest. I think it would enhance their perception of pattern recognition and would increase your own insight.

Tell me if you are interested.

Regardless I will still come.

Ranks

"I have scars on my hands from touching certain people"

The words of Seymour Glass, eldest sibling of the Glass family – a lesser known creation of J.D. Salinger’s literary world. The story of this family of child geniuses, who appeared on a 1927 radio quiz show called 'It’s a Wise Child', is chronicled in three of his books – mostly centering on the relationship between the two eldest brothers, Buddy and Seymour. Salinger favours Seymour. He was the most brilliant and idiosyncratic of all the children and unfortunately, for the most part, only present as a memory – since he committed suicide, age 31.

"Buddy reminisces about one specific Seymour moment: His mother urging him to see a psychiatrist and him telling her that he doesn’t need a head doctor – he needs a hand doctor or a dermatologist, whereupon he looks at his hands and tells her he has these scars – these discolourations on them – from touching certain people. Certain heads, certain colours and textures of human hair leave permanent marks on him. When he put his hand on his little sister Franny’s head when she was still in the carriage, it left a mark. Or with her twin brother, Zooey, when he was six or seven, during a spooky movie. He put his hand on Zooey’s head when he went under the seat to avoid watching a scary scene. It left a mark. Other things, too. Charlotte, the girl he was in love with, tried to run away from him once and he grabbed her dress. It left a permanent lemon-yellow mark on the palm of his right-hand (Salinger 1964:59). His hands were filled with these discolourations – these physical manifestations of his emotions. They became a type of medical condition. And he needed to cure it" (Liebenberg 2011: 93).

Salinger recounts the day of Seymour's suicide in a short story he later wrote, called 'A Perfect Day for Bananafish'.

Poster designed by film director, Mike Mills. His 2010 movie, 'Beginners', is structured as a series of interconnected flashbacks. Following the death of his father, Hal, from cancer, Oliver reflects on their relationship during the last five years, since the death of his mother.

A collection of Echinacea angustifolia tea rings read by botanist and dendrochronologist, Dr Edmund February. A molecule found in the Echinacea angustifolia plant prevents a caterpillar on eating it, from ever turning into a butterfly.

Example of a specimen analysis: “It would appear that the tree stood on a slope since there is more compression on the left hand side, which indicates that side was under less tension. It could also be a branch of which the left hand side would be its underside. The rings are uniformly wide which suggests plenty of soil and moisture availability. In comparison with the other two trees, the outer rings suggest less water or more competition.”

"It is interesting to note that the botanical origins of most of these medicines were from outside of Africa, especially if one considers the long history of the Cape as a point on the trade routes where ill sailors regularly disembarked and drew on the knowledge of the Khoekhoe traditional healers for treatment and herbal cures (Laidler & Gelfand 1971: 44). The Cape flora offered a plenitude of medicinal resources and these healers (who were skilled in botany, surgery and medicine) used them in a variety of healing practices . The exclusion of local botanical remedies in the BWC No. 254 medicine chest can be attributed to many factors" (Liebenberg 2021: 67).

An extract from Kate Atkinson's Human Croquet (1997): "Eunice’s cross-section of a leaf: Photons of light speed down sunbeam arrows for exactly 8.3 seconds and splash through the outer layer of the epidermis and into the heart of the palisade cells. The molecules of light race into the chloroplast, into the perfect little green discs of the grana. The light is drawn further and further in, helplessly attracted by the magnesium at the heart of the little chlorophyll molecules. Light and green embrace, dancing a wild jig of excitement for a tiny fraction of time while the little molecule of light gives up its energy. The chlorophyll molecule is so agitated by this encounter that it splits a water molecule into hydrogen and oxygen molecules. The plant releases the oxygen into the air for us to breathe. The hydrogen converts carbon dioxide into sugar which is used to build new plant tissue. ‘Unlike the plant,’ Eunice notes in bold fountain-pen, ‘we cannot synthesize our own molecules of food from light so we must eat plants or animals that feed on plants and thus without photosynthesis we would not be able to exist".