A slip of the tongue

Ernst Westphal and The Centre for African Language Diversity

A selection of rare audio recordings made by pioneering South African linguist Ernst Westphal is now available online, bringing several extinct and endangered African languages into public circulation again.

There are over 6 000 languages spoken in the world today, but many are at risk of becoming extinct. If language decline continues at the current rate, half of the world’s languages could be gone and forgotten by the end of the 21st century. The Centre for African Language Diversity (CALDi) was established in response to these circumstances, but envisages more widely the promotion and support of the linguistic diversity on the African continent. Our main aim at CALDi is to foster the study, research and documentation of African languages.

UCT’s Special Collections in the Chancellor Oppenheimer Library is home to a vast selection of rare audio tapes recorded by pioneering South African linguist Ernst Westphal between the 1960s and 1980s. A two-phase Humanitec project entailed the digitisation of about 200 of his audio recordings of Southern Bantu and non-Bantu click languages.

‘The Westphal sound files are precious because they include recordings of some languages, which are no longer spoken and of which there is no written record.’

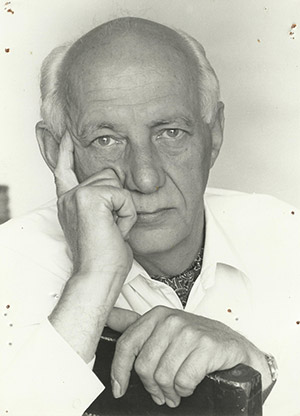

Ernst Westphal

Ernst Westphal

Westphal was Professor of African Languages at UCT between 1962 and 1984, and is best known for his contributions to the studies of non-Bantu click languages, lumped together under a misleading cover term ‘Khoisan’ by other scholars. The Westphal sound files are precious because they include recordings of some languages, which are no longer spoken and of which there is no written record.

Westphal’s recordings allow for the study of vanished regional varieties and lost speech styles of otherwise still widely spoken Southern African languages, such as Southern Sotho, Venda and Xhosa. Of exceptional importance, however, are tapes of languages such as //Xegwi and Kwadi, which Westphal recorded with the last speakers. Several of the recorded languages have become extinct since then. Language diversity is one of Africa’s most essential intellectual treasures. Yet, the majority of the approximately 2 000 languages on the continent are spoken by small communities. Many of these languages are no longer acquired by children and as a result are destined to vanish.

In present day Botswana, most citizens speak Setswana as their mother-tongue and almost all are more or less fluent in this national language. As a result, all other languages in the country are heavily influenced by Setswana. Westphal’s recordings of Yeyi speakers from the 1960s show still very little interference from Setswana. Barbara Westerveld, a student from Leiden University, is affiliated to CALDI and is currently writing her Masters thesis on Yeyi. Westphal’s Yeyi recordings constitute an important source for her studies.

‘Yeyi has been described in previous studies as possessing the largest number of distinct clicks among the Bantu languages; some of the Yeyi clicks seem not to exist in any other language.'

In Southern Africa, speakers of several Bantu languages have borrowed clicks from non-Bantu click languages spoken by hunter-gatherers and pastoralists. Among the more than 500 Bantu languages spread over most Africa south of the equator, only 12 Southern Bantu languages have borrowed clicks. Yeyi has been described in previous studies as possessing the largest number of distinct clicks among the Bantu languages; some of the Yeyi clicks seem not to exist in any other language. For this reason, Yeyi is a very interesting language, but it is endangered.

Weirdly enough though, even though there is a rapid language shift underway with younger people no longer acquiring Yeyi, it is a popular language in music. There are pop songs in Yeyi and well-known artists sing in Yeyi – thus you may listen to Yeyi songs in the radio, but at the same time it is less and less spoken. The number of speakers usually cited is 20 000, but nobody really knows how many people in Botswana and Namibia still speak Yeyi. Barbara is going to conduct fieldwork in Botswana and Namibia and we hopefully will then get a better idea on the extent of language shift and also on the absolute number of speakers.

Barbara will also follow up on stories that relate to Pitoro Seidisa, one of the Yeyi speakers recorded by Westphal. Barbara has to find out if it is true that Mr Seidisa was held in custody for a while before he got a prison sentence, after he returned to Botswana from the recording sessions in Cape Town.

‘Even though there is a rapid language shift underway with younger people no longer acquiring Yeyi, it is a popular language in music. There are pop songs in Yeyi and well-known artists sing in Yeyi – thus you may listen to Yeyi songs on the radio, but at the same time it is less and less spoken.’

The Humanitec grant has allowed students to focus on specific languages, such as isiXhosa, //Xegwi and Southern Sotho, and were asked to help to put the audio files into context. They collected information on the place, date and specific setting of each recording session, but most of all they looked for hints that allow to identify the language consultants, i.e. the speakers recorded on the tapes.

Thanks to the Humanitec project, the Westphal recordings are freely accessible online in digital form. The meta-data production for each audio file constituted an important component of the project, as only detailed accompanying information makes it possible for scholars and others interested people to find recordings of specific languages. Together with UCT library and UCT Special Collections, we have developed a meta-data template, to make the contextual information – word lists, related texts, publications and so on – accessible. Alongside Westphal’s sound recordings, the manuscripts of the Westphal holdings are being digitised. Ultimately, our aim is to link pdf files of those manuscripts to audio files as quite a number of the handwritten notes by Westphal are actual transcripts of the audio files.

The Westphal recordings constitute an important body of precious sources for linguists. In addition, the audio documents are also of great interest to people outside academia, such as the descendants of the speakers or other members of the language communities.

Matthias Brenzinger, director of the Centre of African Language diversity (CALDi) is heading the Humanitec-funded digitisation project of the audio files from the Westphal holdings at UCT’s Special Collections. Brenzinger is an expert in non-Bantu Click languages and is currently conducting research on N/uu, a language spoken by only three people in the Northern Cape.

Matthias Brenzinger, director of the Centre of African Language diversity (CALDi) is heading the Humanitec-funded digitisation project of the audio files from the Westphal holdings at UCT’s Special Collections. Brenzinger is an expert in non-Bantu Click languages and is currently conducting research on N/uu, a language spoken by only three people in the Northern Cape.