Ambient landscapes

The architectural drawings of Ian Ford

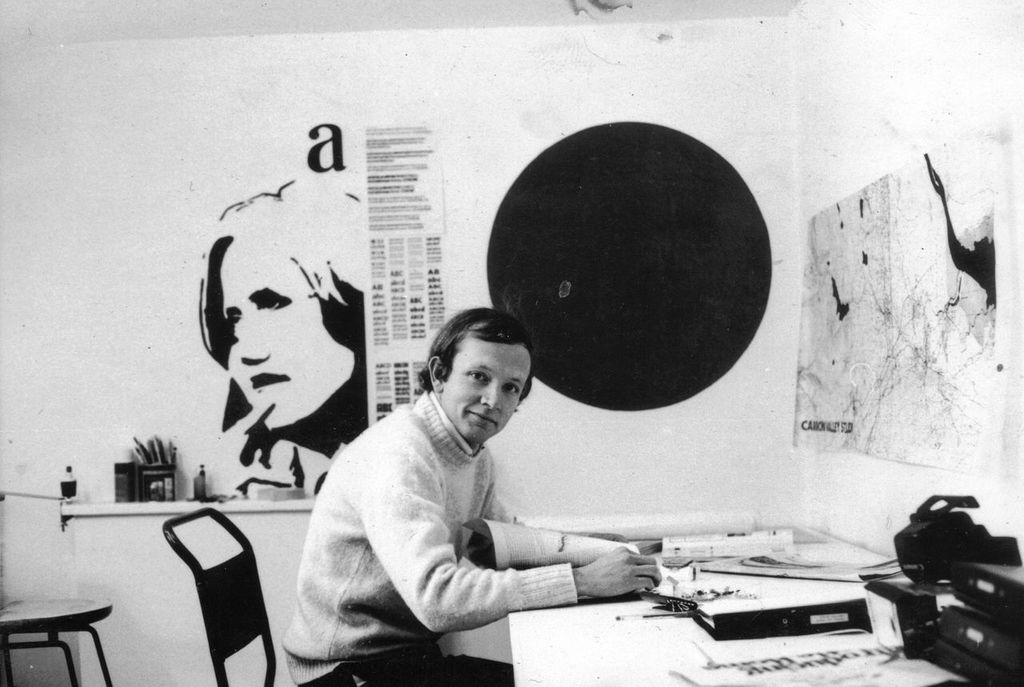

Ian Ford was a landscape architect with a deep understanding of the internal logics of Cape vernacular architecture. His hand-drawn designs are the epitome of pre-digital elegance and subtle skill.

When it comes to landscape architecture, whatever you do in Cape Town is overshadowed by the enormity of Table Mountain or the dramatic coastline. Your attention is always drawn beyond the site to the broader context, so our designs tend to be understated, sublime and subtle. This kind of responsiveness is very much the influence of Ian Ford, although many contemporary landscape architects may not know it.

Born in 1944, Ian Ford studied Architecture at UCT, and then completed his postgraduate studies in Landscape Architecture at Edinburgh University. Landscape architecture is a specialised branch of architecture that deals with the outdoor environment, the public environment, parks, plazas and gardens.

Ian Ford Eulogy

Ian Ford Eulogy

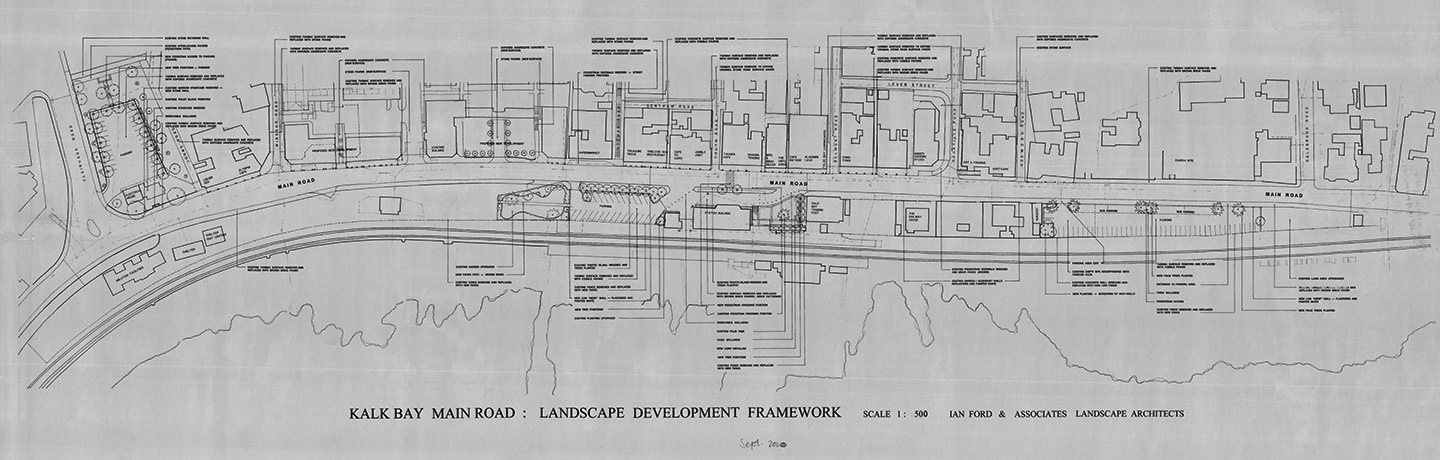

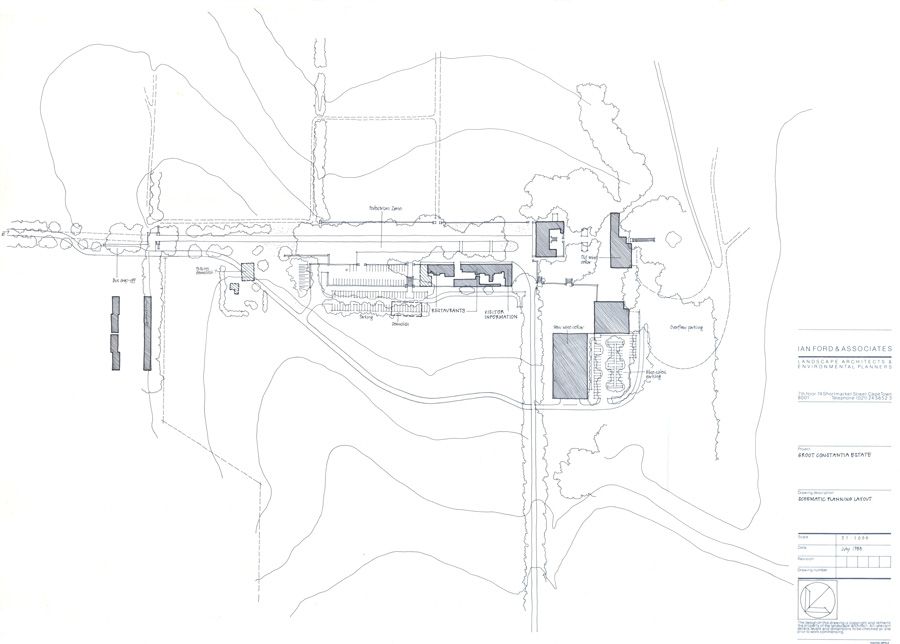

Ian was one of the first landscape architects to establish a private practice in Cape Town, and worked on some very important historic sites and heritage projects, including the gardens at Vergelegen, Groot Constantia, the Company’s Garden, the Parliamentary Precinct and St George’s Mall. Although his oeuvre is vast, he is best known for his subtle interventions into historic precincts – particularly the wine estates.

Tragically, Ian Ford was killed at the age of 57 during a break-in to his home in Tamboerskloof. His murder was a huge shock to the local architecture fraternity.

As a student and graduate of landscape architecture, I had worked for his practice, Ian Ford and Associates. About ten years after his death, Ian’s business partner, Deon Bronkhorst, came to see me about his 30 years worth of drawings that had been stored away in their offices, some of which were starting to get damaged. Considering that Ian was a graduate of UCT, and that he was involved in establishing the Landscape Architecture programme at the university, it seemed right that this wealth of material should become part of UCT’s archival holdings.

‘When I first started working for him, I remember Ian asking me, “Do you think we need to buy you a computer?” And I remember saying, “Oh no, I’m sure I’ll never need one; I’ve got my drawing board.”’

All of Ian’s designs were hand-drawn, which makes them even more precious considering the changes in technology. When I first started working for him, I remember Ian asking me, ‘Do you think we need to buy you a computer?’ And I remember saying, ‘Oh no, I’m sure I’ll never need one; I’ve got my drawing board.’ Of course, drawing boards are almost obsolete now – we do everything on computers. But in the past it was all done by hand. This meant that, if you were working in a scale of 1:100, there was a limit to the amount of detail you could include.

Now, working on a computer, you can work in virtual scale, so you can work in infinite detail. We tend to pack in so much; it can become cumbersome. With computer technology there is the expectation to produce so many more kinds of drawings – three dimensional views and perspectives, photo simulations – so you end up doing more graphic exploration. Yet I don’t necessarily think the design outcome is any better. Ian would be able to refine a drawing in about three or four lines, and it was always beautiful, subtle and elegant. To a certain extent, I think we’re losing skills – finesse, elegance, refinement.

‘Ian would be able to refine a drawing in about three or four lines, and it was beautiful, subtle and elegant.’

Groot Constantia

Groot Constantia

When Deon delivered the drawings to our office in Salt River, they arrived in giant bundles. I had to be very selective about which designs to digitize because there were thousands from which to choose. In order to make the selections, first we had to establish what was there. Luckily, at the time, we had three French interns working for us, so they unrolled all the drawings and sorted them into categories. This enabled us to get a sense of the types of projects at hand. Some of them were interventions at historic wine estates; some of them were urban, inner-city projects, others were house gardens. I started by selecting the most important heritage projects concerning historical sites.

Vergelegen Estate was a really important restoration project, which fell to John Rennie as the architect, and Ian Ford as the landscape architect. Rennie was appointed due to his layered approach to the history of the building. For him, it wasn’t just about restoring everything to the earliest period. If there was an 18th-century aspect to the building that contributed equally as earlier 17th-century aspects, it would stay. Ian Ford had the same kind of approach, valuing these different layers of history in the outdoor aspects of the estate. He believed that it is the subtlety of the layers that gives a place its richness and builds its character.

‘If you go and build a Cape Dutch farm in Johannesburg or South Australia, it’s not going to have the same relevance or fit because it isn’t of the place.’

Although there was a strong influence from the Dutch and other northern Europeans, it is wrong to think of Cape vernacular architecture as a purely colonial import. It is a homegrown style that was developed here in the Cape to suit our local conditions. If you go to Amsterdam, you you’ll find gabled buildings, but they are three or four storeys high – mainly because there is much less space, so they built from a smaller footprint and went upwards. And their buildings are all made out of face brick. The word ‘Holland’ comes from the Old Dutch words ‘holt lant’, which means ‘wood land’. They had lots of wood, so they could bake bricks and fire them. But when these Europeans came here, they realised that, as the local vegetation was mainly fynbos, wood was a limited resource, not be wasted by burning it. So they built using unfired mud bricks, which had to be plastered with thick lime plaster to waterproof them. They could only get a maximum of two storeys out of unfired bricks. And they built roofs with available materials – hence the thatched roofs using local thatching reed. So this architecture was generated as a response to the local environment, local materials. And the style evolved indigenously.

Added to that, a lot of the craftsmen who worked on these buildings were brought from the East as slaves and many were Muslim – so if you look carefully at some of the detail design work on the Cape Dutch buildings, you may find crescent moons and stars and Islamic motifs. It’s a hybrid architecture influenced from the East and the North and built out of local materials in a local context sited in relation to mountain and vista. It’s perfect for where it sits. If you go and build a Cape Dutch farm in Johannesburg or South Australia, it’s not going to have the same relevance or fit because it isn’t of the place.

‘So what can we derive out of this now? We can learn how design should be context specific.’

So what can we derive out of this now? We can learn how design should be context specific. Take RDP (Reconstruction and Development Programme) housing – it is a complete disaster because of its one-size-fits-all approach. The way you build a house in Durban should be completely different to how you build a house in the Western Cape because you’re dealing with different climates and cultures and ways of relating to the street. You can’t apply ‘one size fits all’ ubiquitously. What can we learn from Cape vernacular architecture? We can learn context appropriate responses using local resources.

The wonderful thing about the vernacular is that you don’t build it once and that’s it. It needs to be renewed and maintained. These are skills that we no longer have abundantly. We don’t have many good bricklayers and plasterers anymore because people no longer value those skills or aspire to these crafts. Yet they could be critical to our economy right now. We need plumbers, builders, bricklayers, gardeners – and we need to value and dignify those specialisations.

We have developed a certain shyness around our colonial history, but actually it is very rich and it has influenced the way our cities have been formed. Our vernacular architecture is something worth appreciating and sharing. It’s not exclusive to a particular culture; it’s something of worth to all South Africans. There are certain things that cut across culture – feeling safe and feeling joy and sitting under a tree to eat your meal in the shade. These are human things and we need to focus on those.

‘Landscape architecture offers a different way of approaching heritage because when you’re dealing with plants and trees, which are dynamic and grow and have a certain life expectancy, there is a need for renewal and upkeep.’

Landscape architecture offers a different way of approaching heritage because when you’re dealing with plants and trees, which are dynamic and grow and have a certain life expectancy, there is a need for renewal and upkeep. It can be quite frustrating presenting proposals to the Heritage authorities, where they are trained to think like archaeologists and architects for whom artefacts can be far more static. This archive can reveal how to intervene in the living environment in a way that resonates with the character or historic integrity of a place even as it is living and contemporary and relevant today.

This digitisation project is very much a first step in relation to this archive. There is a lot of potential there – a lot more interpretive work that needs to be done.

Landscape architects look first at the site and then consider how buildings can be placed comfortably within the site. Ian really understood this. If you go to any typical Cape Dutch wine estate, you’ll find that there are beautiful and logical patterns in the way that the buildings relate to the site and to the broader context. Ian understood these patterns, he respected them and he knew how to apply them in a modern way – not as repetition and copying, but as interpretation and contemporary expression.

David Gibbs is a Built Environment professional with an academic affinity. He teaches within the urban design, landscape architecture, city and regional planning programmes at UCT. He co-developed the Mapping Cultural Landscape Toolkit and Syllabus for the Association of African Planning Schools, co-founded the practice, gibbs saintpôl Landscape Architects, and has served as ILASA President, SACLAP Education Councillor, and IFLA Young Professionals’ Advocate.

David Gibbs is a Built Environment professional with an academic affinity. He teaches within the urban design, landscape architecture, city and regional planning programmes at UCT. He co-developed the Mapping Cultural Landscape Toolkit and Syllabus for the Association of African Planning Schools, co-founded the practice, gibbs saintpôl Landscape Architects, and has served as ILASA President, SACLAP Education Councillor, and IFLA Young Professionals’ Advocate.