A Political Awakening

Biography of Mario Pissarra

From an early age I was interested in art and studied Fine Arts at UCT. I was very naïve. I really believed in art as a site of freedom and personal expression, but this was South Africa in the late 1970s and I became very disillusioned with the arts. I felt that they were just a leisure activity for the privileged, so I lost a lot of interest. I was under pressure to take key decisions about my life. I was supposed to fit into this stream and go to the army, but I was very much rejecting the society that I was living in, and art was part of that society.

I left the country to avoid military service and felt that I was leaving all that behind. I didn’t feel part of white society and I wasn’t part of black society, so I felt well actually there was no place for me here. I thought New York would be this amazing countercultural, cosmopolitan liberated space, but I didn’t experience it that way. While I was away – in New York, Lisbon, Harare – I felt extremely displaced and alienated. I didn’t really have the right to be there, so I couldn’t do any proper work. I had become so disillusioned with art that when I was in New York, I didn’t even go to museums. I’d completely lost faith in the whole gallery-centric art world. I was a DJ and I was clubbing at that time; making installations for clubs. I barely entered any galleries.

When I got to Portugal, late 1983, I started questioning why I felt so displaced and to ask myself: Why is there this strong African pull? I started hanging out with Mozambicans, Angolans – Cabo Verde, I’d never heard of, Guinea Bissau, I’d never heard of – all of them roughly my age, whose parents had left after independence. So I came to realise, okay, so I’m this hybrid. I’m not this or that; I’m this and that. I started reading more about Africa and about South Africa’s destabilisation, which I knew was happening, but I didn’t understand. I knew I rejected what was going on around me, but I didn’t actually have the information until then. I didn’t know about scorched earth policies, about how many bridges had been destroyed in Angola – everything. I didn’t know the detail. But now I was reading monthly magazines – Africa Now and AfriqueAsie – and suddenly I was getting educated.

‘I didn’t feel part of white society and I wasn’t part of black society, so I felt well actually there was no place for me here. I thought New York would be this amazing countercultural, cosmopolitan liberated space, but I didn’t experience it that way.’

Then, when I went to Zimbabwe, late 1984, I got another education. A Zimbabwean my age explained to me the difference between the Pan African Congress and the African National Congress, which I didn’t know up until that point. The job I’d travelled to Zimbabwe for fell through, and I got 24 hours to leave so I walked and hitchhiked back to Johannesburg.

I used to deliver The Weekly Mail newspaper on foot. I’d walk to Cosatu and give them one copy, I’d walk to the Council of Churches and give them one copy… But I was reading [arts writer] Ivor Powell in The Weekly Mail and I thought; if Unisa (University of South Africa) can deal with this guy, then they won’t have a problem with me. So I went to a seminar on South African art that [progressive curator] Steven Sack was presenting. This was 1986, and things were starting to get interesting. Now there was an art history that wasn’t just Battiss, Preller and Stern. Here was a version of art history that was giving me more of a local reference point that I could make sense of.

‘I started reading more about Africa and about South Africa’s destabilisation, which I knew was happening, but I didn’t understand. I knew I rejected what was going on around me, but I didn’t actually have the information until then.’

I signed up for a course in African Art history at Unisa and got deep into Yoruba. Lize von Robbroek (co-founder of ASAI) was my lecturer, but we only met years later [because Unisa is a correspondence university]. At the time African art history was all about the ethnographic present, but you were looking at power. How does a masquerade reinforce power relations in present-day Nigeria? I learned that in some cases art was being used to challenge power – political satire etc. Looking at this this way, it all started to come alive for me again.

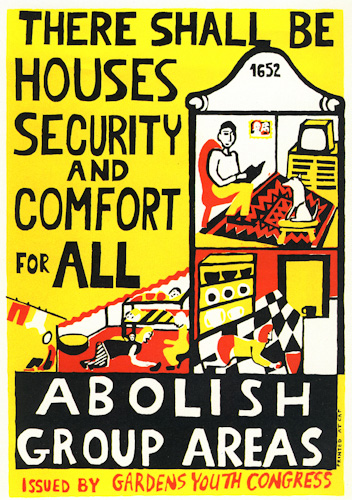

I moved to Cape Town late 1985 and was printing and selling fabrics on Greenmarket Square, and Hayden Proud found me there and suggested that I start teaching African Art at Michaelis. At that point they appointed Michael Godby and art history was moved to upper campus. I was employed as a slide custodian. My job was to make images and I had a lot of latitude, so I was photographing and labelling all the African stuff I could find. I took four years to complete my Honours. I started getting involved in political activism. Before that, I was so scared of being apprehended, that I stayed away. But when the Conservative Party became the official opposition in 1987, there was a group of us that realised that as white people we had no choice but to get involved. So that day about five of us turned up at a UDF meeting in the Gardens and that day was life changing because suddenly I was in another space where people were doing political readings and stuff like that. I was picketing in the mornings and lecturing here…

‘This was 1986, and things were starting to get interesting. Now there was an art history that wasn’t just Battiss, Preller and Stern. Here was a version of art history that was giving me more of a local reference point that I could make sense of.’

I wasn’t really aware of CAP until about 1988, and then there was a lot of mobilization after the Culture in Another South Africa conference in Amsterdam, where people started talking about cultural workers needing to organise. I got very excited about that and started attending meetings – mostly at Community House. I was introduced to a whole new world – people from Khayelitsha and Athlone… I was meeting poets and people who were much better educated than I was in cultural politics and political history, people producing interesting work…

After a while I left UCT where only about five of the mostly white kids I was teaching at the time were interested in the stuff I was excited about. I was very active in the Cultural Workers’ Congress and then started to understand all the internecine politics between the different organisations. I realised how CAP was a no-go zone for people like myself who were, at the time, unambiguously pro-ANC. Yet CAP was very dominant as an arts organisation; it was the most highly resourced of all the community arts projects, so it was a hub or reference point for a lot of activity that happened in the political/cultural sphere.

‘I was introduced to a whole new world – people from Khayelitsha and Athlone… I was meeting poets and people who were much better educated than I was in cultural politics and political history, people producing interesting work…’

CAP’s budget was R1.8-million in 1990 –- almost entirely foreign donor funding. If you look at its funding over the years, there was never one regular source of funding throughout. It came from many different sources, but the Swedes became the mainstay.

I applied to work there several times over the years, and eventually got a job there in 1993. But at that stage, there had just been a major funding crisis and the organisation was at a low point. The budget for most of the 1990s was about half of what the organisation had received at its height. The international funding patterns had changed; you could no longer count on grants from international funders. A lot of people had been retrenched, and they were slowly putting the pieces together again. There was a big focus on adult education at the time, so we embarked on a whole new approach. I worked there until 1999, and it was during that time that I began my work with the CAP archive.

‘CAP was very dominant as an arts organisation; it was the most highly resourced of all the community arts projects, so it was a hub or reference point for a lot of activity that happened in the political/cultural sphere.’