Equality, perhaps

The literary archive of Olive Schreiner’s From Man to Man or Perhaps Only –

The visionary South African novelist Olive Schreiner is best known for her early novel, The Story of an African Farm. But until recently not much was known about the rocky genesis of From Man to Man or Perhaps Only – , which might actually be her greatest literary achievement. Explore her 1876–77 Ratel Hoek Journal, 1886–87 manuscript fragments, 1901 manuscript and 1911 typescript (with manual emendations).

‘Born in the Cape Colony in 1855, the daughter of a German missionary father and a British-born mother, Olive Schreiner first made her name with The Story of an African Farm (1883). However, From Man to Man or Perhaps Only – may well be remembered as the greater achievement,’ writes Dorothy Driver in the introduction to the newest edition, released by UCT Press in January 2016. ‘Schreiner certainly felt it so. The earlier novel, she asserted, was no match for it in “heat”. “I love my new book so,” she later wrote, “a hundred times better than I ever loved An African Farm.”’

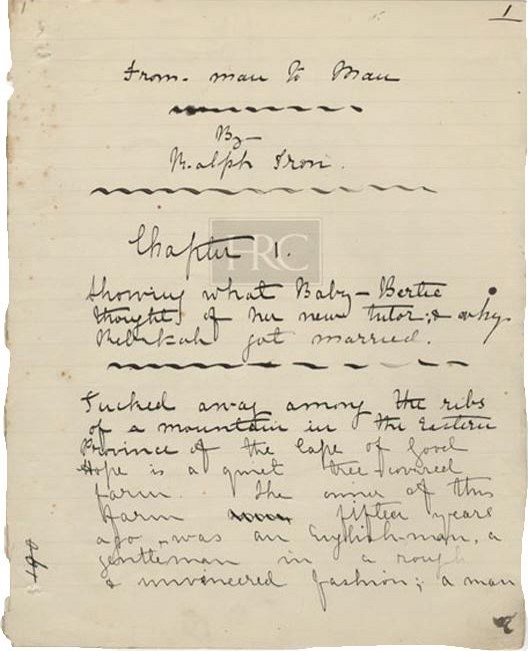

This digital archive was curated in tandem with the release of Driver’s new edition of Schreiner’s magnum opus. The main aim has been to digitally conserve her 1886–87 handwritten manuscript fragments, 1901 manuscript (with revisions) and 1911 typescript (with manual emendations) of From Man to Man or Perhaps Only – and make them available to present and future generations of literary scholars. The paper on which Schreiner wrote is very fragile.

The original artefacts are housed in various library and university collections (the National Library of South Africa, the Johannesburg Public Library and the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin), but they have been brought together into a unified digital archive under the auspices of UCT Libraries Special Collections’ Humanitec project.

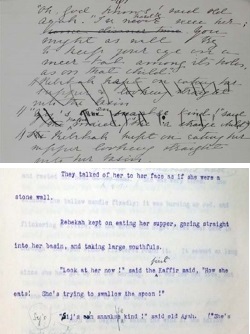

Since Schreiner’s handwriting is nearly illegible to those unfamiliar with it, Driver’s digitised transcriptions offer ease of reading and make the material more readily accessible for scholarly analysis.

Until the advent of this archive, only some of Schreiner’s journal entries were publicly available, and some of these were incorrectly transcribed and published by her husband, Samuel Cronwright-Schreiner (he took her name on marriage).

The relevant pages from Schreiner’s Ratel Hoek Journal, in which she reflects on her thought and writing process in crafting the novel, are also now accessible online. She worked on the novel that would become From Man to Man or Perhaps Only – when she lived and worked as a governess at Ratel Hoek, a farm between Cradock and Tarkastad. Cronwright-Schreiner destroyed the bulk of Schreiner’s journals, as he did with many of her letters. However, Driver notes, he kept those parts that referred specifically to her writing.

‘He destroyed parts of her diaries because he was protecting a secret concerning something that happened to her when she was in her late teens before she left for England,’ says Driver. ‘Cronwright-Schreiner wrote in a letter to Havelock Ellis that “if the world knew what we know about Olive it would set the Thames on fire”. Helen Bradford, the historian, has written a very interesting essay arguing that it was an abortion. But it may have been something else.’

The manuscripts of Chapters 7 to 13 are also lost to us. It appears that Cronwright-Schreiner destroyed them. ‘It is unthinkable that he didn’t keep them,’ says Driver. ‘Perhaps at least parts of them will still be found.’ Schreiner occasionally sent sections of her work to friends and family.

‘I love my new book so; a hundred times better than I ever loved An African Farm’

‘Schreiner had very new and radical views for the time in which she lived concerning gender and race relations in South Africa,’ says Karlien van der Schyff, who was the research assistant on this project. ‘The novel is about two sisters. The one sister marries very respectably, but she feels stifled in her marriage. Her husband cheats on her. She begs him to treat her as an equal and speak to her as if “from man to man”, but he refuses to do so. So it’s a lot about women’s position in marriage. Schreiner saw marriage as a form of prostitution for women. Women needed to earn money in the same way as men so as to be financially independent and their intellectual equals. For Schreiner, that was the only way in which a romantic relationship and even a friendship between a man and a woman could possibly be equal. They needed to be complete intellectual, social and economic equals.

‘The other sister is seduced against her will at a young age, runs away and becomes a prostitute in London. So the story offsets actual prostitution against respectable Victorian marriage, which Schreiner saw as a different kind of prostitution – to stay with a man because you have no other financial choice. Also race relations – the husband of the married sister has an affair with a servant, who gives birth to an illegitimate daughter. Schreiner’s character adopts the child, raises her with her sons, and tries to teach her sons about race and relationships with women. She imagines different possibilities, a different future for South Africa where race and gender relations could be more equal. And this novel was first published in the 1920s.’

‘He destroyed parts of her diaries because he was protecting a secret concerning something that happened to her when she was in her late teens before she left for England’

From Man to Man is an embodiment of Schreiner’s mature political vision. In it her views on empire, colonial relations, warfare, gender, race and class are all knitted together. ‘One can see the author of Woman and Labour, Thoughts in South Africa and Closer Union being the author of this novel. The Story of an African Farm gives only the slightest sense of these authorial identities,’ says Driver. ‘Her awareness of race, class and gender intersections is foregrounded in From Man to Man. The main character changes in relation to these issues and thinks about them much more clearly than Lyndall does in African Farm. In From Man to Man Schreiner was addressing the big questions about power – how male and female get constructed, how black and white reconstruct each other and lock each other into position. There is, for example, an absolutely clear emphasis on who is doing the work in the household. Instead of just referring to packing, for instance, the novel shows the maid doing the packing. Schreiner recognises the presence of servants to make their servility apparent in the text. But she also gives them an increased agency and even an ironic presence and vision at times.’

Schreiner began drafting From Man to Man in the 1870s, in her late teens, while working as a governess in the Karoo. When she departed for England in 1881 she took the manuscript with her, but wasn’t able to get it published.

‘Through much of the 1880s, which Schreiner spent mostly in England and Italy, she was hard at work writing and revising, and doing much else besides,’ writes Driver. ‘She continued work on the novel, albeit more sporadically, between 1889 and 1913 when she was back in the Cape.’

‘Seeing the manuscripts and manual emendations helps give us a sense of Schreiner as a subject-in-process’

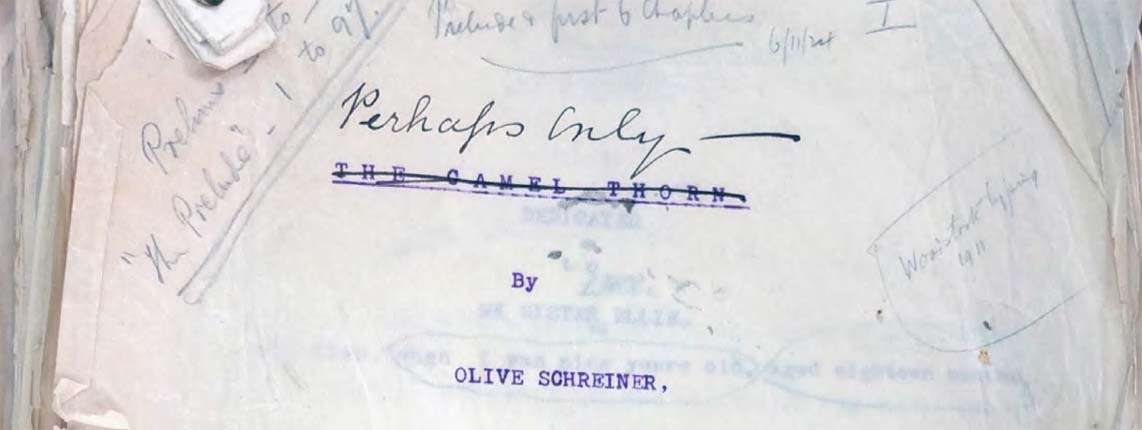

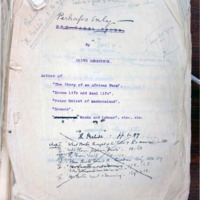

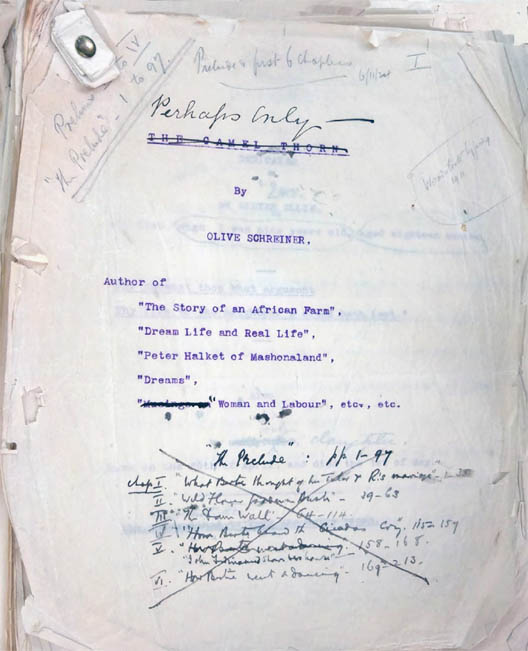

Although Schreiner had been using the title ‘From Man to Man’ since the mid-1880s, she inked the words ‘Perhaps Only –’ above the new title ‘The Camel Thorn’, which appeared on the incomplete typescript dated 1911 [see picture story].

After her death, Cronwright-Schreiner began sorting the manuscript pages, getting them typed, making manual emendations and getting the pages re-typed. He combined the new handwritten title with the one she had most often used, and had the novel published in 1926.

‘Since its first publication – initially in Britain, thereafter in the US – From Man to Man has been re-issued several times for both markets, most recently in 1982. Until now, its sole appearance in South Africa has been in a somewhat unwieldy compendium volume, issued in 2004, which includes Schreiner’s two other full-length novels, African Farm and Undine,’ writes Driver. ‘Like the other editions of From Man to Man, this one was marred by many of the proofreading and editorial errors of Cronwright-Schreiner’s first edition.’

Driver had two major aims in editing the current edition: first, to make available a remarkable novel by the pre-eminent South African novelist of her day – a work that has been out of print as a stand-alone text since the mid 1990s; and, secondly, to produce a text that is closer to Schreiner’s original aims. As part of her editorial work, Driver looked anew at Schreiner’s letters, her manuscripts and the emendations on the typescript Cronwright-Schreiner worked from.

One of the most important adjustments in the new edition is the ending. ‘Cronwright-Schreiner appended to Chapter XIII an account of the ending that Schreiner had apparently planned and recounted to him,’ writes Driver. ‘The present edition reproduces this account but it adds another: a particularly detailed, informative and interesting extract from a letter Schreiner wrote to Karl Pearson in 1886, which is, of course, unlike Cronwright-Schreiner’s version, in her own words. Her words fit the tone of the novel in a way that his words do not. He sentimentalises, dramatises, makes certain things spectacular. He keeps things in the realm of the individual and romantic in a way that she did not. This letter extract is in Appendix 1, where it precedes Cronwright-Schreiner’s account.

‘Neither of these projected endings can be taken as definitive. What Schreiner communicated to a husband and a friend may well have been to some degree geared to each interlocutor.’

Besides raising questions about the ending given in Cronwright-Schreiner’s edition, the present edition also expands on his account of the novel’s genesis. Under the heading ‘A Note on the Genesis of the Text’ Cronwright-Schreiner included in his edition a selection of brief quotations from Schreiner’s journals and letters.

‘You can see Schreiner’s passionate engagement in her handwriting. When she adds more commas, for instance, it is as if her hand is beating out the pulse of the prose’

Driver’s edition offers a considerably expanded selection, now entitled ‘Genesis and Composition of From Man to Man’, drawing on far more of Schreiner’s correspondence than her husband had access to. It also includes notes on the recipients of the letters in question.

The current edition also expands on the original annotations to the text. ‘Schreiner’s and Cronwright-Schreiner’s footnotes are retained, but additional annotations provide historical, linguistic, botanical and other information on a variety of issues likely to be of interest, and perhaps of use, to the many different kinds of readers and scholars Schreiner’s writing attracts,’ writes Driver.

It is hoped that increased accessibility to this material will give rise to a wider recognition of what might be Schreiner’s most important novel, and a greater understanding of how her progressive views on race, class and gender equality fed into her writing. ‘From Man to Man was composed over a lifetime, and the changes its author underwent sometimes give it a layered, sedimentary feel,’ says Driver. ‘Except on a few occasions, specific sections can’t be dated with any precision, but seeing the manuscripts and manual emendations helps give us a sense of Schreiner as a subject-in-process, as the French psychoanalyst Julia Kristeva would put it.

‘The wonderful thing about the digitisation process is that you can see Schreiner’s passionate engagement in her handwriting. When she adds more commas, for instance, it is as if her hand is beating out the pulse of the prose. You get a sense of her physical presence in the text. It is very moving because she was so passionate in her conviction that storytelling could change the world. You can feel her passionate urging that we should hear her stories, that we should tell our own stories, that we should interact with the world to change it in a human way.’

Dorothy Driver is Professor of English at the University of Adelaide, and Emeritus Professor at the University of Cape Town, where she taught for 20 years. She has also held visiting positions at the University of Chicago and Stanford University. Her major research interests have been in the constructions and representations of gender and race under colonialism, apartheid and after apartheid, and in writing by women. Her literary research and analysis has covered various South and Southern African writers, including Nadine Gordimer, Bessie Head, Noni Jabavu, Njabulo Ndebele, Pauline Smith, Yvonne Vera and Zoë Wicomb, as well as treating topics such as the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, Drum magazine and gender, the African National Congress constitutional guidelines, and short fiction in English during the ‘fabulous fifties’. She recently re-edited Olive Schreiner’s major novel From Man to Man or Perhaps Only – , published by UCT Press.

Dorothy Driver is Professor of English at the University of Adelaide, and Emeritus Professor at the University of Cape Town, where she taught for 20 years. She has also held visiting positions at the University of Chicago and Stanford University. Her major research interests have been in the constructions and representations of gender and race under colonialism, apartheid and after apartheid, and in writing by women. Her literary research and analysis has covered various South and Southern African writers, including Nadine Gordimer, Bessie Head, Noni Jabavu, Njabulo Ndebele, Pauline Smith, Yvonne Vera and Zoë Wicomb, as well as treating topics such as the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, Drum magazine and gender, the African National Congress constitutional guidelines, and short fiction in English during the ‘fabulous fifties’. She recently re-edited Olive Schreiner’s major novel From Man to Man or Perhaps Only – , published by UCT Press. Karlien van der Schyff is a PhD student at the University of Cape Town. Her main research interests include feminist theory, postcolonial theory, embodiment theory and South African literature. She writes about representations of female bodies in Olive Schreiner’s From Man to Man in her PhD thesis.

Karlien van der Schyff is a PhD student at the University of Cape Town. Her main research interests include feminist theory, postcolonial theory, embodiment theory and South African literature. She writes about representations of female bodies in Olive Schreiner’s From Man to Man in her PhD thesis.