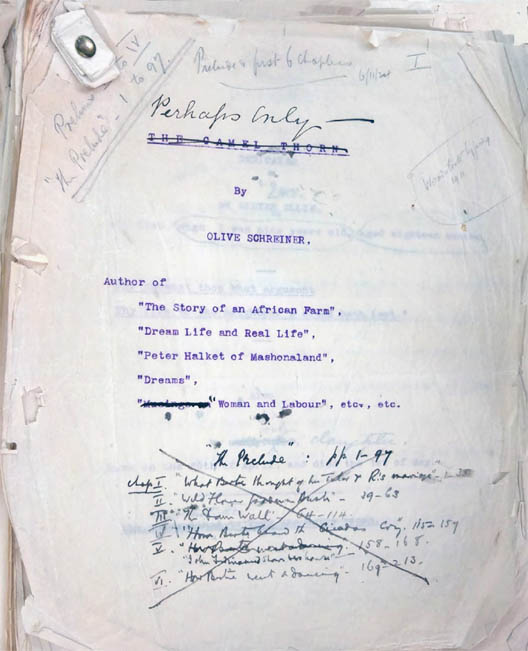

Camel Thorn

'

What of “The Camel Thorn”? It is impossible to know if Schreiner had ever mooted this title in her letters, since not all the letters are extant. However, perhaps the words had taken on particular significance for her when she was revising the last chapters, even if they were not yet ready to be typed. Although the camel thorn tree (Vachellia erioloba) is very like the sweet-thorn (Vachellia karroo) that Schreiner speaks of in the Prelude, and is also quite common in the Karoo, it is all the more common in Central Africa, where Rebekah’s friend Drummond has been travelling. When Drummond and Rebekah meet, and Drummond spends time with her sons, telling them stories about his travels, he talks of the camel thorns and the anthills that Rebekah has already spoken of to her children. She has told them of an ancient African landscape of camel thorn and anthills, a space that long, long predates the arrival of Europeans. The great anthills of this ancient African landscape are “as high almost as a man”; “slowly and slowly they have grown a little and a little higher”. The building of anthills is symbolic of social progression. “The most that any nation can hope for, is this: [that man], in the one little hour of life that is given him […] may be able to add one tiny grain, so small perhaps that no eye will ever see it, to the heap of things good and beautiful which men have slowly been gathering together through the ages […] so … that all coming after shall say—‘It was nobly done!’”

‘One may assume that Schreiner’s choice of “The Camel Thorn”, which refers us to this African landscape, coheres with her more general interest in turning to African culture for the changes it can make to the European. This theme has been increasingly pressing on Schreiner’s imagination. And it is in this regard that Rebekah stresses to her children that civilisation depends on contributions from many different people, each offering their “tiny grain” of sand. Hierarchies cannot be fixed: one group may be ‘superior’ in one respect, another may be ‘superior’ in another. Each group, each person plays an important part.

‘However, in 1911 Schreiner strikes out this title, and writes “Perhaps Only –” in its place. The words come from the Prelude: “Perhaps only God knew what lights and shadows were!” The sudden uncertainty is a feature of Rebekah’s thinking too: “The agony of life is not the choice between good and evil, but between two evils or two goods!” This open-endedness reminds us that Schreiner did not complete the revisions to From Man to Man or Perhaps Only —; she appears to have given up some years before she died. During the lead-up to the Act of Union in 1910, she was in political despair at the increasing greed and individualism of white South Africans who were betraying the political and economic interests of their fellow blacks. At a key point in the novel, she has Rebekah say, “My dream ends here”. The words “Perhaps Only –” reach out towards a future that Rebekah cannot articulate, but which Schreiner’s African landscape helps us imagine. The novel suggests that yet another “grain” of sand will be added by Rebekah’s youngest children: one a foster-child, the other a biological child; one black, one white; one female, one male. Their eyes are full of dreams.’ – Dorothy Driver